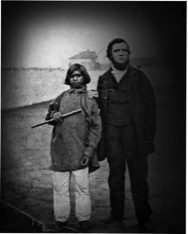

David Unaipon & the Reverend George Taplin, c 1879. Photographer unknown. Reproduced in Australian Aborigines: AFA Annual Review, Aborigines’ Friends Association, 1935, p. 16

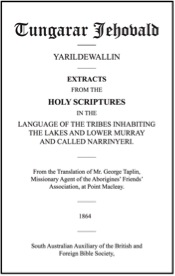

In 2014 we celebrate 150 years since Bible Society published the first Australian Aboriginal scripture. It was in the Ngarrindjeri language of the lower lakes region of South Australia. Bible Society is preparing celebration events with Wycliffe Bible Translators who are celebrating 60 years of Bible translation work in Australia. A community day celebration will be held with the Ngarrindjeri people in Raukkan on the shores of Lake Albert. A joint publication called Coolamon Kids has been released as an aid in learning about Bible translation into Indigenous languages.

Though it is important to acknowledge Bible Society’s role in publishing Indigenous scriptures over the last 150 years it is equally imperative to recognise that Bible translation in Australian has a chequered history. As a nation Australia has one of the highest rates of language extinction on the planet. Of the over 250 distinct Indigenous languages spoken before European invasion only 145 are still spoken and of these 110 are critically endangered .

Title of original 1864 edition of the Ngarrindjeri scriptures.

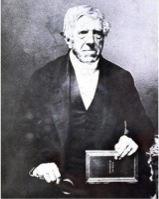

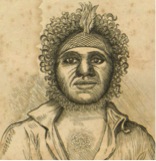

The very first scripture published by Bible Society Australia was not an Australian language but scripture selections in the Maori language of New Zealand printed in 1827. It wasn’t until 1837 that an Aboriginal language had scripture translated. This was in the Awabakal language spoken around the Newcastle region of NSW. Rev. Lancelot Edward Threlkeld began missionary work among the Awabakal people on the shores of Lake Macquarie in 1824 and devoted many hours to learning and speaking the Awabakal language. With the assistance of Birabaan, his Awabakal tutor, he mastered the language and his revolutionary missionary strategy was, “First obtain the language, then preach the gospel” (Threlkeld to Bannister, 27 Sept 1825). In 1829 the first draft of St Luke’s Gospel was completed. However, it was not until 1892 that this translation was published, 33 years after Threlkeld’s death. Threlkeld believed himself a failure due to a lack of conversion by the Awabakal people and by 1840 few Awabakal people remained at the mission. Why Threlkeld and Birabaan’s work took nearly 60 years to publish could be due to a lack of understanding of the impact of translating the Bible into a person’s heart language.

Reverend Lancelot E. Threlkeld, mid-1800s, from the John Turner collection University of Newcastle, Cultural Collections.

Curiously, as we celebrate the publication of the Ngarrindjeri scriptures in South Australia we see a similar despondency with missionaries Heinrich August Eduard Meyer and George Taplin . Lutheran missionary Meyer wrote to his supporters in Dresden in 1848, “I have nothing pleasing to impart…I could not achieve anything among the blacks” (as quoted by Dr Mary-Anne Gale, “Nothing pleasing to impart? H.A.E Meyer at Encounter Bay, 1840-1848”). Yet their work with local Ramindjeri and Ngarrindjeri translators James Ngunaitponi (David Unaipon’s father) and Tinmani was a beginning of Bible translation in South Australia. The true success of the work of all these people was in their relationships of mutual respect which by default necessitated learning one another’s languages. There continues today a community of Christians at Raukkan who attribute their faith heritage to the work of Ngunaitponi, Tinmani, Meyer and Taplin. Ngarrindjeri Elder Verna Koolmatrie confirms this mutual respect, “You need to build trust with people before they will enter into a dialogue with you.”

It is to our shame that, up until 1980, in the hundreds of languages in Australia, only two New Testaments were translated. Fortunately in the last 50 years there has been significant increase in Indigenous Bible translation primarily through the Australian Society for Indigenous Languages (AuSIL) established by Wycliffe Bible Translators in 1961. In partnership with Wycliffe, the Uniting Church and CMS, Bible Society has now published 11 New Testaments since 1980 plus numerous Gospels portions and in 2007 published the Kriol Bible – the first complete Bible in an Australian Aboriginal language.

The first Torres Strait Islander scripture portions were published in 1900 in the Kala Lagaw Ya language followed by the same four Gospels in the Meriam Mir language. For the past 27 years Wycliffe Bible Translator’s Michael and Charlotte Corden have been labouring away with Torres Strait Islanders to complete the New Testament in Torres Strait Yumplatok. Bible Society published this volume in July this year. It also includes the books of Genesis, Ruth and Jonah.

Biraban, drawn by Alfred Thomas Agate.

Still many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Christians have access to only portions of the Bible in their heart language.

Our prayer is that Bible Society Australia, along with our mission partners and local Indigenous translators, and with support from our donors, can continue to publish and distribute Indigenous language Bibles as translations become available.

Enduring Voices, a National Geographic program to encourage language preservation states: “Studying various languages also increases our understanding of how humans communicate and store knowledge. Every time a language dies, we lose part of the picture of what our brains can do.” At Bible Society Australia we believe each time a language dies we lose a part of God’s complete design for humanity and creation – in the choir of Christians a voice is silenced and prevented from praising God our creator and the whole choir suffers its loss.

—–ENDS—–

NOTES

[i] Prior to 1788, over 250 Aboriginal languages were spoken. At the time of the 2005 survey, only about 145 Aboriginal languages were still spoken, with most of these languag

es (110) categorised as “severely and critically endangered” by global linguistic experts. Only 20 Aboriginal languages are considered to be “strong.” in Statement to the Australian Government on the Inquiry into Language Learning in Indigenous Communities, conducted by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs Committee, December 2011, p2 available at http://nationalcongress.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/111214-CongressSubmissionLanguageIndigenousCommunities.pdf

[ii] Information about Lancelot Threlkeld obtained from Niel Gunson’s article in the Australian Dictionary of Biography at http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/threlkeld-lancelot-edward-2734, John Harris’s article at http://webjournals.ac.edu.au/journals/adeb/t/threlkeld-lancelot-edward-1788-1859 and from the University of Newcastle’s “People and Place | Coal and Community” site at http://www.coalandcommunity.com/threlkeld.php

[iii] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biraban

[iv] Information about George Taplin obtained from John Harris’s article at http://webjournals.ac.edu.au/journals/adeb/t/taplin-george-1831-1879/ and also from G.K. Jenkin’s article in the Australian Dictionary of Biography at http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/taplin-george-4687

[v] In Yunti Ngarni Lakun Thunggari ‘Together we are weaving our language’ compiled by Mary-Anne Gale with Eileen McHughes and Phyllis Williams 2013 ISBN: 978-0-9805425-2-3

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?