Can ‘Christian’ political parties survive?

Christian Democrats need a massive overhaul says former state director

Survivors of Cory Bernardi’s Australian Conservatives are trying to keep the party going despite the founder deregistering it. Meanwhile a recent Christian Democrats NSW State Council meeting descended into chaos – a story broken in Eternity.

The future of Australia’s Christian – or mostly Christian –small political parties is in question. A longtime insider of conservative politics, in the Coalition and outside it, Greg Bondar, says desperate measures are needed.

Scott Morrison’s ‘miracle’ win has been attributed to the growth of faith-based voters among his coalition of ‘quiet Australians’. But at the very same election, the ‘Christian’ parties were reduced to one-percenters, hopelessly short of upper house quotas.

Vigorous policy debates over religious freedom, possibly amplified by the Israel Folau controversy, gave conservative Christian voters in 2019 a real incentive to vote for parties – such as the Christian Democrats (CDP), and possibly the Australian Conservatives, which went all out for their votes.

But they flocked to the Coalition instead.

The rise of religious consciousness among voters in the 2109 election contrasts with the slow decline in Christianity in Australia.

The religious Left complicate the voting patterns.

The most recent ABS Census (2016) in Australia shows that 12.2 million Australians (52 per cent) identified as Christians. According McCrindle Research, 33 per cent of Australians consider themselves Christian in a more considered sense (eight million people) while 9 per cent actively participate in a church or community of faith (1.6 million people) – far more than go to sporting events that require a gate fee. The decline in Christianity apparently reflects changes in family structure – relatively fewer two-parent families raising their children to faith and in church. At the same time, though a smaller proportion of the total population, the number of Christians has remained fairly stable, reflecting the growth in population by immigration.

According to a recent ABC News report, the ‘religious Left’ is growing and, while they may not wield the same political power as the Christian Right, it is emerging as a diverse, passionate and active voting bloc in Australia. While conservative Christians on the right identify with a distinct set of issues such as same-sex marriage, euthanasia, religious freedom, and abortion, the religious Left complicate the voting patterns. The ABC’s Karen Tong comments that while there’s a “clear commitment to social justice among the progressive and pious on the religious left, they’re not wholly subscribed to the Left’s full agenda.”

Do religious political parties such as the CDP have a future? As the former federal and NSW state director of the CDP and campaign director for the 2016 federal elections, I was always taunted by secular colleagues with slogans such as “so you work for the Christian Declining Party” or Christian Decimated Party or Devastated, Demolished, Destroyed, Diminishing, Dwindling, Disappearing or indeed “Christian Deteriorating Party.” I soon began to better understand the implications and the extended meaning of Matthew 5:11, Matthew 10:22, or John 15:21 – all of which highlight the secular abuse Christian apologists face daily.

Christian Right candidates have always had a difficult task in any election but their even worse track record in the 2019 election is a perfect window into trends that will set the pace of Christian politics for decades to come.

The process of secularisation has been moving rapidly in Australia compared to the US, where a study by Pew Research found that 23 per cent of Americans say they’re “unaffiliated” with any religious tradition, up from 20 per cent three years earlier. In Australia, the McCrindle research in 2017, Faith and Belief in Australia, explored the state of Christianity in Australia. The purpose of the research was to investigate faith and belief blockers among Australians and to understand perceptions, opinions, and attitudes towards Jesus, the Church and Christianity. In that study 44 per cent of respondents did not identify with any religion whatsoever.

In the same study, the biggest blocker to Australians engaging with Christianity was the Church’s stance and teaching on homosexuality (31 per cent said this completely blocks their interest). This was followed by ‘How could a loving God allow people to go to hell?’ (28 per cent) which explains the public reaction to Israel Folau’s ‘hell’ tweets.

I am neither a brain surgeon nor a rocket scientist, but my sense tells me that this trend away from faith is only bound to increase with time. The trends are that more adults under the age of 50 are opting out of religion and claiming ‘no faith’ is now the fastest growing ‘religion’ in Australia.

Within the political Right, the argument is put that enough of these these people will return to the sanctuary and back into the conservative parties such as One Nation, Australian Conservatives and, of course, the Liberal Coalition. The argument might be a comfortable one to conservatives of faith, but it is not supported by the facts.

This demographic trend is creating what we could call the ‘Undecided Unbelievers,’ a voting disparity that is particularly harmful to Christian-based parties.

The implications of Australians’ exodus from cultural Christianity are significant for the political Right because the religiously unaffiliated appear to have a real preference for Greens, One Nation and perhaps even one-issue parties. In fact, a person’s religious perspective is generally the most accurate predictor, aside from party identification, of how he or she will vote.

The fact is that many voters are abandoning faith and, as they do, they are leaving Christian political parties (CDP) as well. This demographic trend is creating what we could call the ‘Undecided Unbelievers,’ a voting disparity that is particularly harmful to Christian-based parties (CDP) since the Liberal Coalition and One Nation have been much better at getting votes from among Christians than the CDP has among the irreligious (the ‘Nones’).

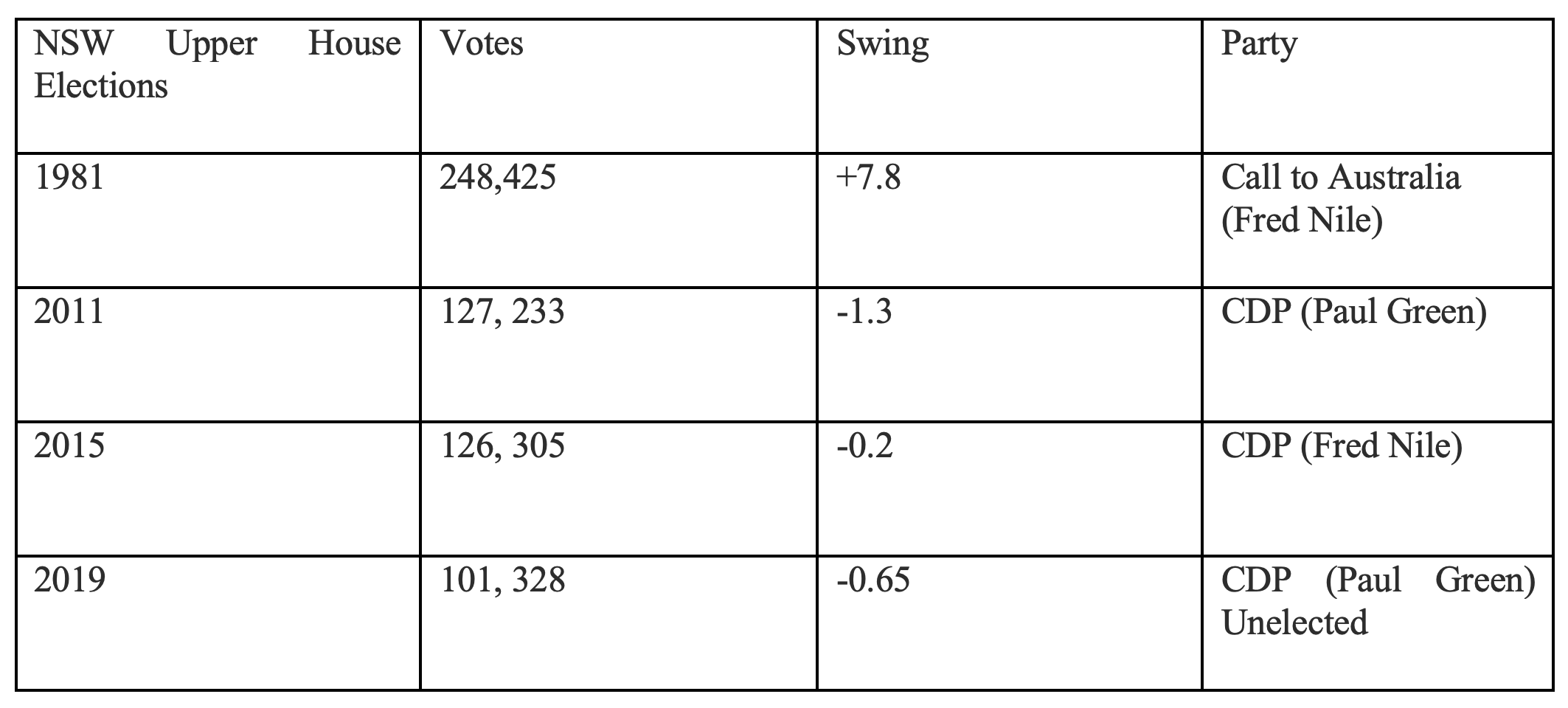

Data on past elections indicates a marked decline for CDP support since 1981.

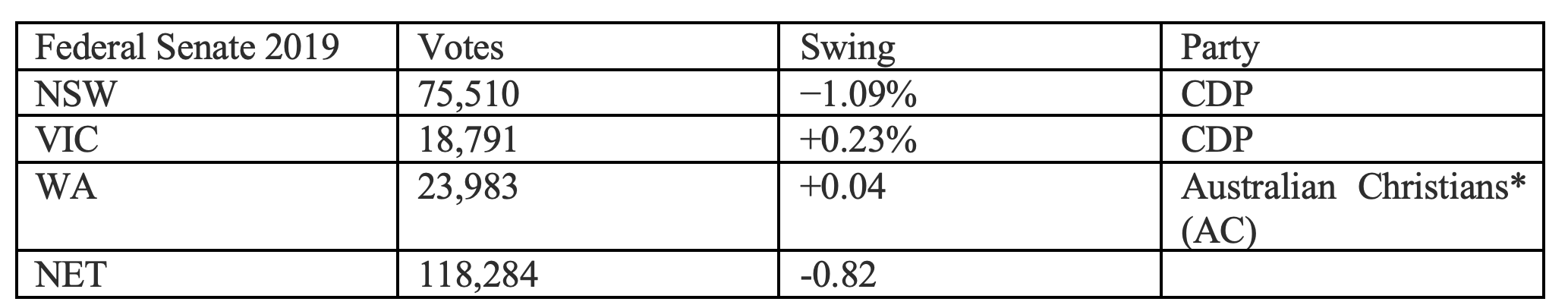

Federally, the CDP and Christian parties didn’t fare much better.

AC formerly ‘split’ from Christian Democratic Party (Fred Nile Group) 2016

The likely reason why CDP support has declined in popularity, especially among the non-religious, is CDP’s long tradition of identifying itself as a Christian party and pushing the “Judeo-Christian values” at any cost and at the expense of economic and social policies.

CDP’s choice: Onward Christian soldiers or political reality?

As a former and active political adviser in the first term of the Howard government, I was often guilty of bowing down at the altar of public opinion just to win votes. I, along with many other Christians in politics, have had to choose between our Christian ethics and the realities of politics. This is now the choice CDP must face.

As bad as things are now for CDP with regard to secular voters, however, they seem to be worsening. So, unless action is taken – and this must include a concession that most Australians support same-sex marriage – as the non-Christian portion of the country continues to grow, the prospects for the Christian- based CDP movement are going to attenuate as the ‘Undecided Unbelievers’ grow.

They need to restructure the party in terms of name, leadership and candidate selection.

In loving sincerity, here are the hardcore options for Christian political parties and CDP in particular. First, they need to reinvent themselves. The word ‘Christian’ in a political party name no longer resonates with the electorate. While I am not advocating any form of political apostasy, Christian political parties à la CDP, need to rebrand with a view to bringing the ‘Undecided Unbelievers’ from the anti-Christian wilderness into the Christian-tent. To do this they (CDP) need to restructure the party in terms of name, leadership and candidate selection.

Christian-based policies need to be more encompassing and certainly more ‘hip-pocket’ oriented

Second, the Christian political movement needs a new champion to wave the Christian flag. When Fred Nile came to the NSW electorate in 1981 under the Call to Australia banner, he was waving the Christian flag and saw a successful 7.8 per cent swing. The Christian political movement desperately needs a new Fred Nile who is articulate, engaging, honest, compassionate, flexible (but uncompromising) with integrity and optimism. Many thought the Australian Conservatives (AC) leader Cory Bernardi was the likely new pseudo-Christian champion, but alas the AC polled pathetically in all the states (0.5 per cent in NSW) with little or no apparent impact on the electorates.

Third, while not abandoning traditional biblical principles, Christian-based policies need to be more encompassing and certainly more ‘hip-pocket’ oriented. Policies need to correlate Christian beliefs with economic and social issues of homelessness, unemployment, heath, ageing population, housing affordability, and so on.

Last, any Christian-based party such as the CDP needs to engage with its constituent base – the churches. For far too long, churches have been reluctant to enter the public arena space claiming that church and state cannot be sitting in the same pew. As an apologist for FamilyVoice Australia, I am constantly defending the Christian faith. If we are to make disciples, then more than ever we need committed Christians in politics.

If we are to make disciples, then more than ever we need committed Christians in politics.

Any Christian-based political party will need to ensure that it embraces the resources and the spiritual wealth within the houses of God (1 Timothy 3:15; Hebrews 3:6; and 1 Peter 4:17). The prognosis is clear: voting patterns of regular churchgoers in Australia consistently favour the Coalition, according to the National Church Life survey. In 2016, 41 per cent of church-attending Christians voted for the Liberal-National Party, and 24 per cent voted for Labor. If Christian-based parties such as CDP are to succeed, they will need to tap into the 65 per cent of church going voters.

As we approach 2022 and beyond, Christian conservative parties such as the CDP face a choice. They can continue to pigeonhole their politics and become a small group of frustrated Christian traditionalists who grow ever more resentful toward their fellow Australians. Or they can embrace reality – following a faith that wants Christians to first put their affairs in order and then render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s. If they opt for the second, they can continue at the same time to carry out the Great Commission.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?