'You can't speak your language. You can't change the Bible ...'

How Bible translation is restoring a town, a language, a culture

Charmaine Councillor used to be scared at the thought of translating the Bible into her traditional Noongar language because other Christians considered it a bad thing to “mess with God’s word.”

“My Aunty told me, Nana said to her, You don’t touch the Bible. She was brought up in the mission, so that was her special book. But then some other teachers, missionaries, said that you got to learn this word. And so a lot of the old people got influenced that you can’t speak your language, you’ve got to learn this English.”

Reviving their damaged language has been an emotional journey for the Noongar people, who live in southwest Western Australia, around Bunbury.

People like Charmaine’s uncle, pastor Len Wallam, grew up forbidden to speak their language, so it became associated with trauma and loss of self-esteem.

“What inspired me the last two days is that you don’t have to give up your land, you don’t have to give up your language.” – Charmaine Councillor

“Uncle was chastised many times by many other Christians saying, ‘When you become a Christian, you got to give up everything,’” Charmaine told a Bible translation conference in Darwin this week.

“And what inspired me the last two days is that you don’t have to give up your land, you don’t have to give up your language. So my own uncle left the legacy for someone like me and my other family to continue.”

People from many language groups from across the Northern Territory attended the conference, which was organised by Bible Society Australia (BSA) and held at Nungalinya College. But Phil Townsend of Bible translation organisation SIL Australia/Timor Leste told the conference that only 46,000 of Australia’s 812,000 Aboriginal Australians speak a traditional language that is robust enough to be used every day.

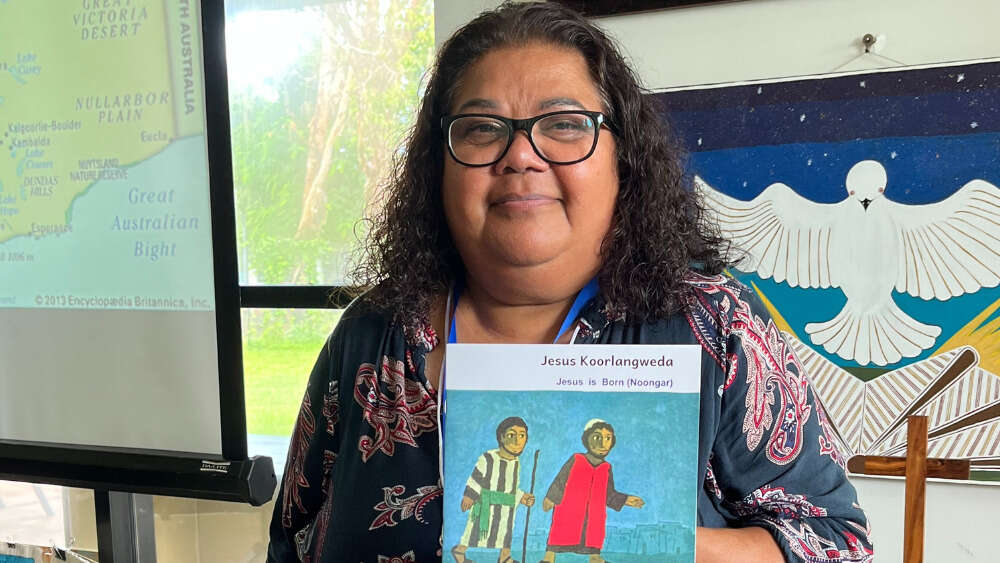

Charmaine Councillor, left, with Amy Cruickshanks, BSA translation consultant.

Charmaine told Eternity that for a long time, she didn’t feel ready to pick up the translation work begun by Pastor Wallam, which led to the publication of the Noongar Book of Luke in 2014.

That book was a world first in a damaged language. It has the Noongar on the left-hand pages and an English translation and glossary of the Noongar words used on the right-hand pages. Then in 2020, the Story of Ruth in Noongar (Bardip Ruth-ang) was published.

“It’s a very important world first in the sense that it is a very serious work in a language that was in the process of being lost. And this Scripture will enable that language to be maintained,” comments BSA’s translation expert John Harris, who pioneered and continues to work on the Noongar project.

“For 20 years I went to Perth to work on this language that was dying, but I had to find the language. They could speak it a little. So they couldn’t speak it in full, and I had to go through 19th-century sources where people had written down the language and so on, and eventually they could write the language.”

Speaking on video, Harris says: “Len was an angry man. He was angry because of the loss of his land being taken from him. And he was angry because of language being taken from him – because he been beaten when he spoke his language and put it away in a dark place. And he came to the first of the translation meetings and he translated [a verse of] Genesis 1.”

After this, he went back to preach on that verse in his own language in the pulpit. His hands – which had always been fists when he preached – became open, with his palms towards the people.

Harris concludes: “People say, ‘Why can’t they read English?’ which they can. But this book means more to those Noongar Christian people than some of the Bibles of people who speak fully their own language in some parts the world because it’s giving them back something. We have damaged them so much.”

“We started to set up a little language hub in our community in Bunbury …” – Charmaine Councillor

Charmaine recalled: “Back in the early years, I saw my Uncle Leonard starting to go off on these strange trips to Perth. Where was he going? He went to Perth and he said, ‘I’m going to translate the Bible.’ But at that time I wasn’t ready. I didn’t have the capacity in my language. I didn’t have the spiritual capacity at the time to be mature enough to be able to work with him,” she explained.

“[But] when he’d always come back to church and tell us what he had researched or come up with, sometimes he’d ask me for a word. ‘Go find that word.’ And so it was a nice thing to do at the time.”

Charmaine later became a teacher and the Noongar project fell into abeyance for several years after her uncle and other elders of the translation group died.

“And then we had a language centre developed in Bunbury. I was the education officer at the time, and I was going out teaching language to communities of the local clans in my area. Then the language centre closed down and moved to Perth. I lost my job. So then we started to set up a little language hub in our community in Bunbury, and the same elders would come into the classes every week.”

At first, Charmaine held the classes around her dining table, but then they moved into a back room in the church.

At first, Charmaine held the classes around her dining table, but then they moved into a back room in the church.

“It wasn’t a Christian-based program, they just wanted to learn our language, but it was growing and growing. And then all of a sudden, we had a little celebration when the Bible Society launched the book of Luke and somehow conversation started. We all gathered together as we all talked to each other, saying, ‘Do you think we could revive this again? Do some more work?’ My name popped up in the conversation and, anyway, it stemmed from there. Now we have a language Bible translation class and we have a general language class.

“What’s great is that our Noongar, who have been learning our language for the last 30 years for us, but not in this capacity. So we have to be more equipped, more trained, and that’s where I think now I’m actually ready to move on with the work that Uncle Len started and others who came before us. I’m honoured to be able to be the next generation taking it through. I hope that someone will follow after us.”

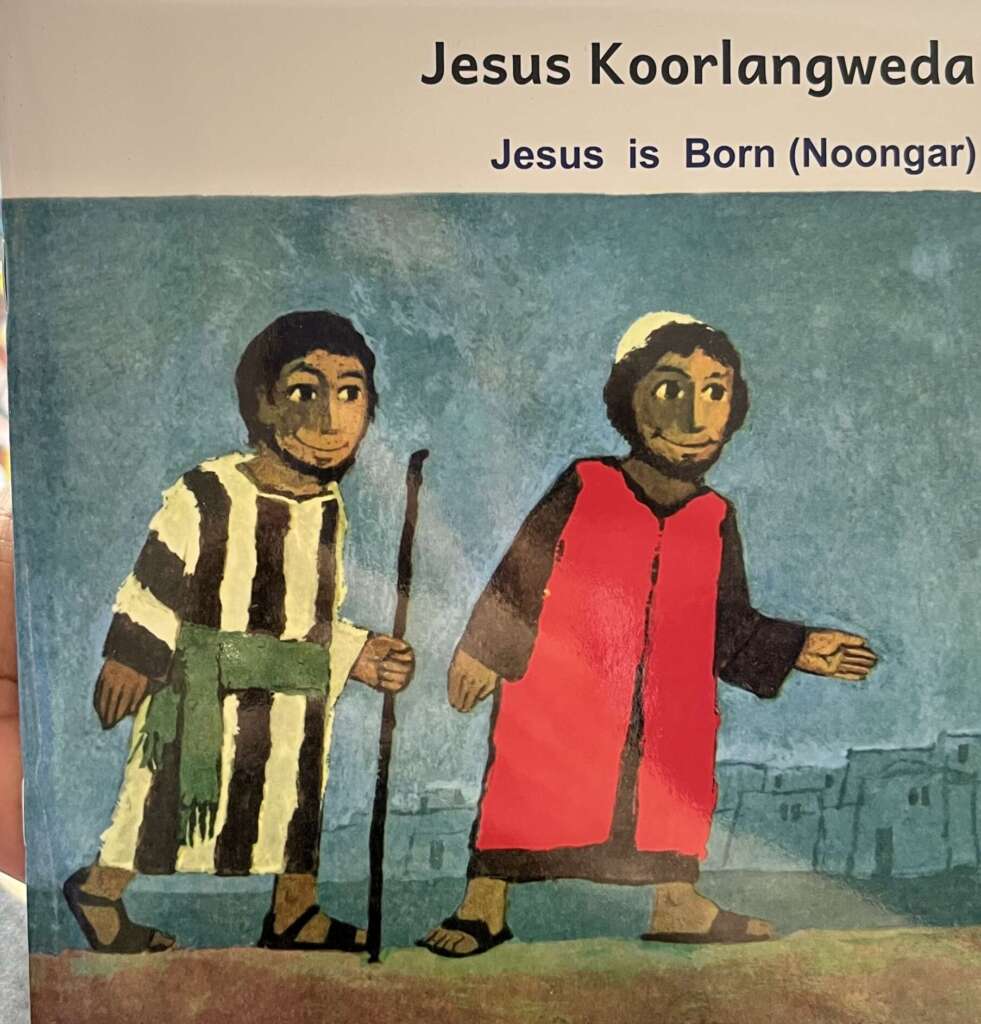

BSA translation consultant Amy Cruickshanks showed a little book of the Christmas story for children in Noongar that was launched last year, which Charmaine was involved in translating.

While this Christmas story, Jesus Koorlangweda (Jesus is Born), is not a direct passage from the Bible, now Charmaine is working on translating Genesis 1.

“So now we’re into the Bible stuff, so we’ve slowly gone from language class feeling like, ‘Hey, do we want to do this?’ to where they’re ready to do it, and it’s absolutely thriving,” Amy said.

Charmaine says the translators are so enthusiastic they try to skip ahead to surprise John Harris with their homework before they get online on Zoom with him.

Charmaine says the translators are so enthusiastic they try to skip ahead to surprise John Harris with their homework before they get online on Zoom with him.

“It’s such a passion of ours that we don’t wait for the next lesson. We just start trying writing because our team have been writing language for some time now, but not to this extent where it’s getting more difficult to explain concepts.”

Amy adds: “We’ve got another one coming out soon. Watch this space for another little book. So there’s lots of stuff coming up.”

Speaking to Eternity, Charmaine explained that while the project had champions, it also faced opposition from Noongar people because of the buried trauma of the past.

“I didn’t realise how much embedded it was in me, until someone said to me, ‘Oh, we don’t have that language in the church here.’ And I said, ‘But that’s who we are.’ And we’re challenging this right now. A couple of people in our community are saying, ‘We don’t want the language in the church, in our services, we don’t think it’s right,’ because their mindset is still back there. They haven’t been on that healing journey of language. So they say, ‘This is a gospel and you don’t change the gospel.’ And we’re getting our linguists to try to explain to them that it’s a translation of another language.

“I didn’t think it was a big issue until that came up recently. I think some people associate language with trauma – it’s a dark place.”

“Bible translation has been helpful in restoring our people’s esteem because we were told we weren’t a language, we weren’t a people.” – Keith Truscott

Perth-based Aboriginal elder Keith Truscott, who is now involved in translating the book of Matthew, said on the video, “Bible translation has been helpful in restoring our people’s esteem because we were told we weren’t a language, we weren’t a people. Language is very important to build up our esteem and strengthen us for today so that our tomorrow will be even stronger.”

Charmaine told the conference she didn’t understand the depth of God’s word until she started to look at it and break it down and to hear it spoken back in another way.

“It’s actually given me permission not to give up my culture and my language,” she said, apologising for getting teary.

“It helped me reconcile God’s word and I don’t know what I’ll do if it wasn’t for this type of work. I was so scared at the thought of translating God’s word because it was considered a bad thing.

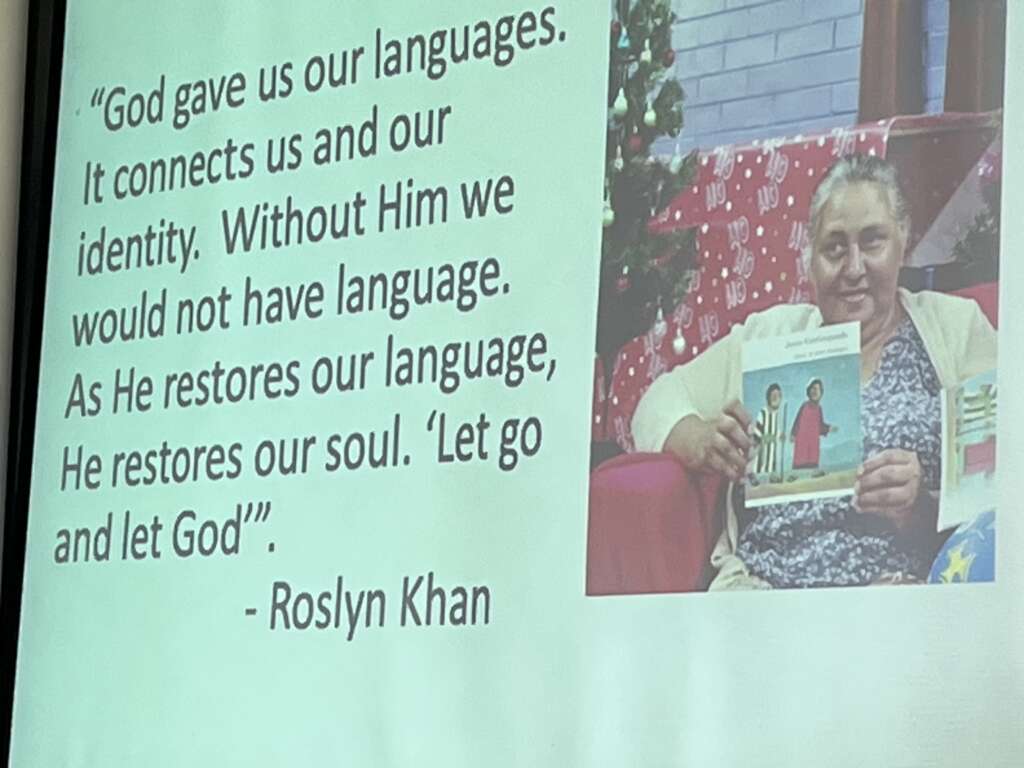

“But God gave us our languages, and it connects us to our identity; without him, we would not have language. As he restores our language, he restores our soul … It actually is healing.”

Charmaine adds, “For that person that wants to revive their language and do Bible translation, you can never overestimate how much joy and healing it can bring to you as an individual people, in the nation and healing on country.”

“They’re all actually getting in on the Noongar language revival.” – Charmaine Councillor

Charmaine told Eternity that as well as being taught in schools, the use of Noongar is gathering pace in the Bunbury community in consultation with the elders.

“There are programs happening in our communities, lots of language classes, little groups popping up everywhere.

“They’re all actually getting in on the Noongar language revival. And it’s all different approaches: art, song, storytelling, dance. A lot of festivals are using it now, and the biggest thing that’s happening in our local townships and cities is dual signage. So Bunbury has actually now embraced dual signage.

“As you’re coming in [to Bunbury], there’s a billboard, ‘Welcome to Noongar country’. We’ve even got signage about the historical places all in language and a bit of history about the Noongar people.

“The local community, the local city councils love it. We had just named a brand new skate park last year. It’s called Koolambidi Woola, which means place of young people … So there’s some real champions in our community.”

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?