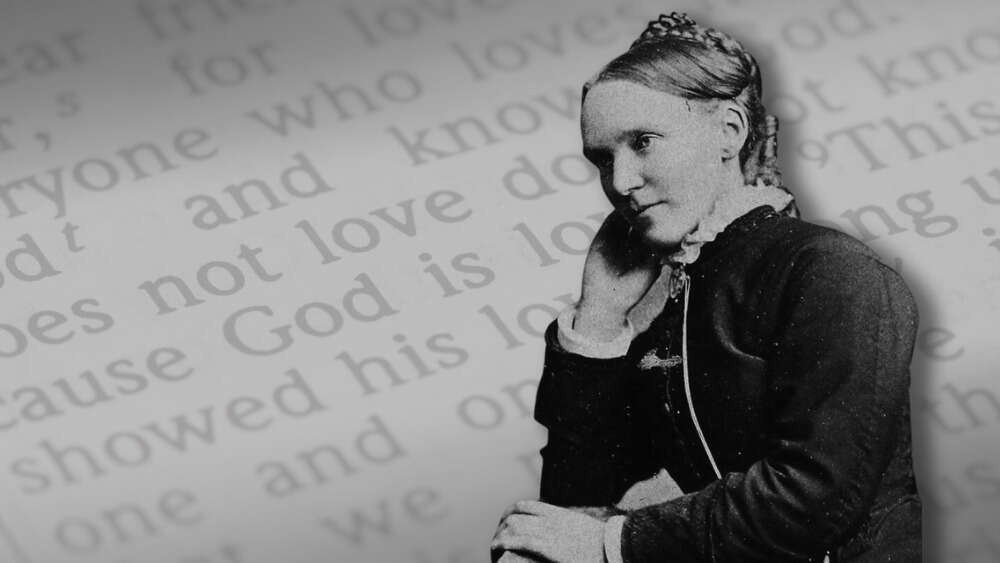

In 2006, the popular Sydney evangelical worship band Garage Hymnal released their hit album, Take My Life. Its title was drawn not from a contemporary song, but a classic nineteenth-century hymn composed by Frances Ridley Havergal in 1874. Garage Hymnal’s popularisation of a hymn from the other side of the world in another century says much about its timeless appeal. Its call for wholehearted discipleship has spoken powerfully to the hearts of believers everywhere, from rural parishes in Victorian England to metropolitan congregations in Sydney today.

Born on 14 December 1836, Frances Ridley Havergal was the youngest of six children born in the Worcestershire village of Astley in England’s west country. Her father, William Henry Havergal, was a Church of England clergyman who belonged to the evangelical wing of the church. Like his daughter, he was also a hymn writer and composer, and was rector of St Peter’s Astley when Frances was born. In a nod to their evangelical sensibilities, William and his wife Jane christened their daughter Frances with the middle name “Ridley” in honour of the sixteenth-century bishop and Anglican martyr, Nicholas Ridley.

With William and Jane cherishing this Reformation heritage of Anglicanism, young Frances was raised in a home of warm, evangelical piety. While always encouraged to accept the grace of God in Christ, the young Frances had wrestled with her faith, often doubting her worthiness before Christ and living in fear of the judgement to come. At the age of 14, however, Frances experienced a spiritual awakening and came to be assured of God’s salvation and forgiveness, giving her inner joy and peace.

Given Frances’s own formidable intellect, a striking quality of her hymns was their sheer simplicity, reflecting a child-like faith in Christ as her personal Lord and Saviour.

Frances inherited her father’s gifts for writing and music. From the age of three, she learned to read books and exhibited her linguistic talents, rapidly learning German, followed by French and Italian. Gifted with a brilliant memory, she soon learned large portions of the Bible off-by-heart, including the Psalms and the minor prophets. This laid the foundation for her works of poetry and hymn writing.

As the cultural movement of Romanticism swept through the church, the Victorian era witnessed a great outpouring of new hymns and new hymnbooks. A large number of these were composed by devoutly evangelical women including not only Frances herself but Catherine Winkworth (1827-1878), who translated several German hymns, and the American Frances Jane “Fanny” Crosby (1820-1915), who wrote Blessed Assurance and To God be the Glory.

Given Frances’s own formidable intellect, a striking quality of her hymns was their sheer simplicity, reflecting a child-like faith in Christ as her personal Lord and Saviour. Avoiding theological complexities, her hymns conveyed simple evangelical truths accessible to the ordinary worshipper. Her hymn In Full and Glad Surrender emphasised total surrender to the lordship of Christ, while I Am Trusting in Thee Lord Jesus spoke of an abiding trust in Christ alone for personal salvation. In perhaps her most famous hymn Take My Life and Let It Be, the message is one of radical discipleship, with the believer consecrating their whole life to God.

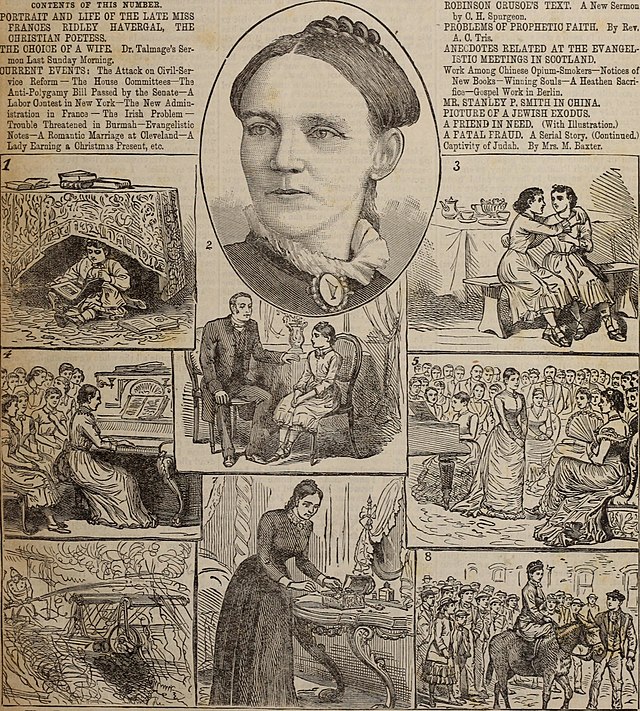

Portrait and article on Havergal in the Christian Herald, 1886 Unknown Author / Wikimedia Commons

While Frances became most famous for her hymn writing, she led a full and interesting life, despite suffering bouts of ill health that eventually claimed her life at only 42. Aside from reading and writing, she loved travelling to Europe and hiking in the Swiss Alps. Immersing herself in the rich culture of Europe, she enjoyed the concerts of great German composers, such as Ferdinand Hiller. A musician to the core, Frances was a talented singer and pianist who played the works of Handel, Beethoven and Mendelsohn. On one visit to France, she delighted the audience with her piano playing in a hospice run by the Catholic Church.

Frances remained single her whole life, yet enjoyed warm relationships with her parents, siblings, nieces and nephews. Like the Apostle Paul and other single men and women of God through the ages, she evidently used her singleness as an opportunity to devote her time and talents to the service of God and his people. In addition to her writing and musical pursuits, she taught Bible classes, visited the poor and contributed to the ministries of CMS, the YMCA and the Bible Society.

With many of their hymns still recognised and sung today, female hymn writers such as Frances left a legacy that stood the test of time.

In a period where the leadership of evangelicalism was both clerical and male-dominated, laywomen such as Frances emerged as important voices of the movement through the lyrics of their hymns. Music and hymn writing provided an invaluable outlet for Victorian women to not only articulate their Christian beliefs but to impress these on a popular audience through song. In doing so, they arguably had just as much, if not more, impact on popular evangelical piety than many of the leading theologians and preachers of the day.

Often set to lively and spirited melodies, the hymns of these women gifted the evangelical movement with much of its spiritual vigour and vitality, just as the hymns of Isaac Watts, Charles Wesley, John Newton and others had done in the preceding 18th century and beyond. With many of their hymns still recognised and sung today, female hymn writers such as Frances left a legacy that stood the test of time.

Like the classic works of literature, many of these hymns have been bequeathed from one generation to the next. From the dusty pages of old hymn books to iTunes playlists, this has given evangelicalism that essential sense of historical continuity perhaps more characteristic of other Christian traditions. In singing these hymns today, evangelical worshippers can feel like they are treading the very steps in which the saints of old have trod, identifying with their griefs and joys, their struggles and their hopes in the same Christian pilgrimage to John Bunyan’s “Celestial City” (which represents heaven in his book The Pilgrim’s Progress).

The albums of modern bands like Garage Hymnal attest to the enduring legacy of this bright yet short-lived candle of English hymnody. As one of the lead hymn writers of the Victorian age whose hymns are still cherished and loved, the story of this understated yet talented musician, writer, polymath and daughter of Anglican Evangelicalism deserves to be told.

This is an edited version of the conference paper David Furse-Roberts presented at the Evangelical History Association Conference 2023. David is a Research Fellow at Menzies Research Centre and an Electorate Officer at the Parliament of NSW.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?