Why Christos Tsiolkas is keen to talk to Christians

Writer of The Slap declares he’s fallen in love with Paul

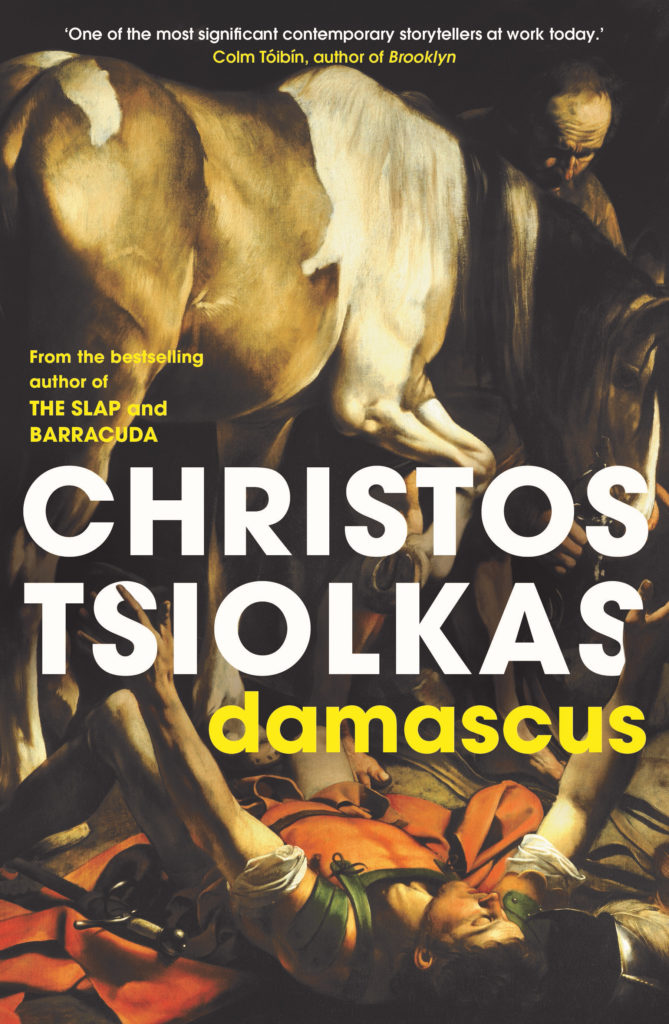

There were times while reading Christos Tsiolkas’s new book, Damascus, when I had to peep through parted fingers shielding my eyes. Such is the horrific brutality of the world it portrays – the ancient world of the early worshippers of “Yeshua” (Jesus) and the Romans who condemned them and threw Christian slaves to wild animals for entertainment.

It starts with Saul being the chief accuser of a woman – a girl, really – who is stoned for adultery. Then after this zealous Jew is attacked by a blinding light on the road to Damascus, it describes his struggle to overcome the scandal of mingling with slaves and women before being baptised and “reborn into the light.”

The novel vividly portrays how outrageous Christianity’s message of equality before God was in this caste-ridden Greco-Roman society, where girl babies were abandoned on a mountain to be eaten by wild dogs and fellowship with slaves was considered an abomination.

It is an amazing imaginative feat, but a challenging read for a Christian, not only because of its dark, animalistic imagery but also because it mixes Paul’s expressions of profound gospel truths of love, hope and forgiveness with heresies such as the apocryphal legend that Yeshua had a twin brother, Thomas, who preached against the resurrection.

But Tsiolkas calls it a “sincere investigation” and welcomes the opportunity to talk to Christians about his book.

In Tsiolkas’ portrait, Paul is a tormented soul – struggling with shame and sin, terrified at having been chosen by God to take the good news of Jesus to the world and tormented by his exile from his family, his tribe and his land.

But the Greek-Australian author of international bestsellers The Slap and Barracuda insists he has come to love Paul through his reading of his letters.

“I don’t think you can write a book about faith without writing a book that is also about doubt,” he tells Eternity .

“Paul – Saul of Tarsus, not the saint because a saint mythologises him and makes him into an icon – I was really fascinated by the man – a living, breathing, struggling, terrified, brave man, what that meant. And you can’t read Paul’s epistles without seeing someone struggle with both faith and with doubt.”

Tsiolkas wants to make it clear that while he is very much influenced by Christian ethics, “it’s been a very big and long journey to come to a kind of reconciliation and peace with Christianity for myself.”

Tsiolkas wants to make it clear that while he is very much influenced by Christian ethics, “it’s been a very big and long journey to come to a kind of reconciliation and peace with Christianity for myself.”

In a departure from his usual way of working, Tsiolkas spent a year in which he did no writing at all but simply read the New Testament, along with early Christian and Gnostic writings and philosophy. He also travelled to Rome, Turkey, Israel and Greece, walking in Paul’s footsteps.

“It’s been close to six years of my life now – but longer, it’s been a long, long time that I’ve been thinking about these things – but when I decided to start work on this book, that first year I didn’t write; I just researched and read. I went back to the Bible and I went back to theology, and I went back to history and I went back to philosophy and I feel like I’ve been a student for the first time in my life. And my partner Wayne, he’s lived with all my books, and he said ‘what you’ve learned through this book will never leave you.’”

Tsiolkas’ feelings for Paul have changed radically since he first encountered his writing as an adolescent, when he was feeling the shame of experiencing same-sex attraction. He had just turned 13 and the family had moved from inner-city Richmond in Melbourne to Box Hill in the outer suburbs at a time when “I was being besieged by the evil of my sexuality.”

What I discovered there were incredible passages of what it means to struggle to be human and what it means to finally find the peace of God’s love. It was almost as if I could listen to him for the first time.

Having grown up in the Greek Orthodox church, Tsiolkas only knew Paul as an icon on a church wall until a “wonderful woman” who belonged to a Baptist church introduced him to Paul’s letters. He found that he couldn’t get past the stricture against homosexuality in the verse from 1 Corinthians that was made famous recently by rugby player Israel Folau.

“I couldn’t read him [Paul]. All I could feel was this sense of exile,” he says.

Unable to reconcile his Christian faith with the imperative to honour his sexuality, he “proudly and defiantly and angrily” declared himself an atheist at age 15.

“I am profoundly moved by Jesus’ words and his best interpreter is Paul.”

Coming out to his Greek migrant parents was terrifying for Tsiolkas and a source of shame for his parents, who lived in a community that never had frank discussions of sex and sexuality. After his father died, Tsiolkas was surprised to discover that his mother had found strength to go on living by reading Paul’s letters in her Greek copy of the Bible. She said “I realised, through Paul’s works, that God loves you.”

During his late 20s, during a period of confusion and despair, Tsiolkas walked into a Uniting Church “and I found myself praying, I found myself just falling into prayer after a long time of not doing it and I started reading Paul from that moment.

“And unlike the child at 13, what I discovered there were incredible passages of what it means to struggle to be human and what it means to finally find the peace of God’s love. It was almost as if I could listen to him for the first time. And since then he’s been important to me because I love the letters and because I do think – even though I’m not a Christian because I don’t believe in the resurrection and it would be wrong to call me that – I am profoundly moved by Jesus’ words and his best interpreter is Paul.”

Tsiolkas welcomed the opportunity to talk to Eternity about Damascus because: “It’s really important to me that I have discussions with Christians about this book. I hope it feels like a sincere investigation. That is what keeps drawing me, when I say I love Paul, because that’s precisely what I hear. Unlike the younger me, I don’t hear exile or derision – I hear love. My mother hears love when she reads Paul. Paul was really important to her to come to terms with accepting me, her son’s sexuality, because she heard love in it.”

Tsiolkas says he has been battling with the idea of what it is to be a moral and good person in the world for a long time, and a lot of his books have been about the question of faith expressed in different terms.

After abandoning his Christian faith, he grasped for another faith and found socialism, which led him to travel through Europe after the fall of communism and the writing of his third book, Dead Europe.

“And, again, I came to a point of crisis with that. Travelling through eastern Europe and seeing the enormity of what communism had done – I called it my road to Damascus moment – I had to really think through and go, ‘I have espoused this belief that was quite tragic in its consequences.’

“[Christianity] doesn’t only belong to Christians. It’s a legacy that is for the whole of the world.”

“But I think what connects Damascus and Dead Europe is just as, because of 2000 years of the institutionalised church, so many atheists I speak to condemn all of Christianity because of that history – I wanted to go back to first principles for myself and remind myself of what was really deeply challenging and deeply, profoundly important for me, from my youth. And it is the best of Christianity I don’t want to give up on; and I – I hope it’s all right to say this – it doesn’t only belong to Christians. It’s a legacy that is for the whole of the world. That compassion, that forgiveness. So, I did write this book for myself, but what I would hope is that people who come to it will find that in the reading.”

For Tsiolkas, the most revelatory aspect of Christianity is how Jesus, a man who came from the humblest of backgrounds, “has this profound understanding of what I think God’s grace must be, absolutely profound. That’s a miracle for me; even beyond the miracles that have become part of our popular lore, that to me is the most miraculous thing about Christianity, that he could say something like ‘If you are without sin, cast the first stone’, which has been probably the biblical teaching that has been most important for me.

“I was a little boy in primary school and a very wonderful teacher told us that story about Jesus coming across the adulteress about to be stoned. And I was so moved by those words.”

He says he is grateful for the experience of writing this book. “It’s actually been one of the greatest joys of my life working on this book. Yes, it’s been hard, but it’s also been one of the greatest joys.

“I think on one simple level it’s the joy that comes from being able to understand the richness of history. I feel like a student in the best sense of the word, that I now realise I’ve got so much to learn. I’ve got so much to read and that’s exciting at the age of 54 to feel that the world is opening up for you.”

Tsiolkas’s favourite passage of Scripture is from Paul’s letter to the Galatians.

“It is that we’re not woman or man, we’re not master or slave, we’re not Jew and Greek, we are all one in Christ Jesus. That is beyond anything. That is another miracle, the appearance of the universal, that is the passage that always moves me,” he says.

“The other one that you can’t read without being so grateful is Paul’s words on love, because that’s when you go ‘this man understood Jesus.’ In thinking about it you can’t help but be moved, right? ‘Love is patient, love is kind, love does not boast.’ It still speaks through the years and, again, it wasn’t until working on this book that I was able to hear it anew without the words becoming cliché, without them becoming something you put in a greeting card.”

Having wrestled with Paul for a long time and finally saying goodbye to his rage and bitterness towards Christianity, Tsiolkas says he has understood something about patience through Paul’s letters.

“I know he’s waiting for the return of Christ, but every single one of those letters – and it weaves in and out – there’s a lesson there to learn about patience. I think that’s been a really important thing that I’m really grateful for, that I’ve got from working on this book.”

Damascus by Christos Tsiolkas (Allen & Unwin $32.99)

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?