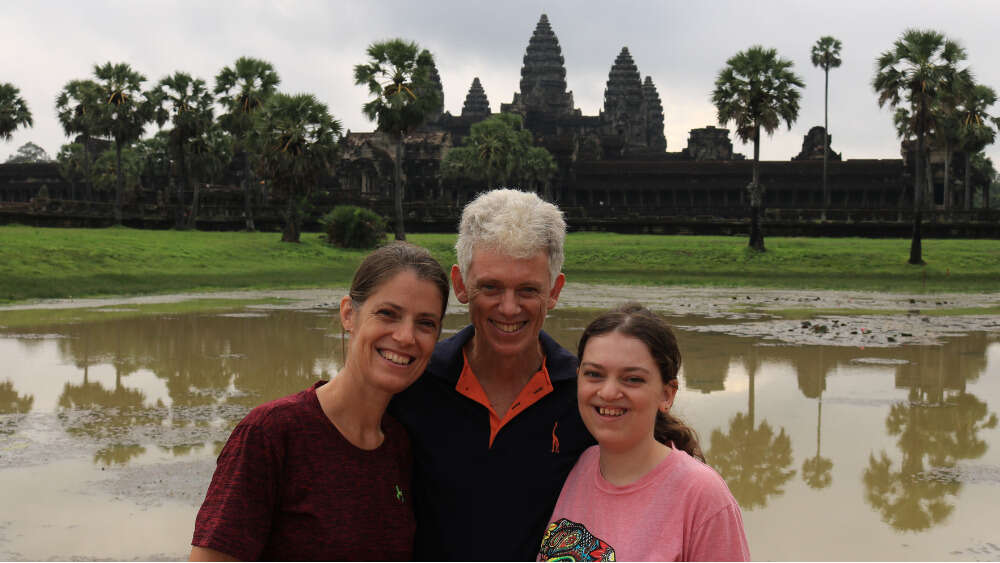

Dave and Leoni Painter have served the Lord in Cambodia with the Church Missionary Society since 2001, recently as teachers at Phnom Penh Bible College. They are currently on home assignment in Sydney.

About 15 years ago, Leoni and I were sharing with a small group in Australia about our missionary work in Cambodia. We had been discussing the importance of taking the time required to become proficient in the local language, understand the local culture, develop relationships, and commence ministry in a small way. Then one participant asked: “How long have you been there now?” (“Six years!”) “Haven’t you had your turn? Shouldn’t you let someone else have a go now?”

More recently, a fellow missionary (who was about to return home after five years) said to me over lunch one day that I was an old-fashioned missionary, who tried to learn the language (rather than engaging the services of a translator) and stayed a long time… the implication being that newer (more effective) missionaries did not need to stay so long to make an impact!

Thanks to the constant prayer and the sacrificial financial giving of so many Australian supporters over these years, we have (only by the grace of God) completed six terms in Cambodia with CMS so far (since 2001). While we are on home assignment, it seems timely to reflect on our missionary experience and share something about the costs and benefits of long-term service.If we define long-term mission as the giving of the best part of your working life, then this generally means giving up your secular professional aspirations (or those of your parents). I was a local government engineer at a time when this was generally regarded as a job for life providing a good salary and other benefits (company car, generous superannuation and a career path leading to much civic responsibility along with a commensurate salary for those with sufficient ambition). Public service hours were great, leaving me time and energy to prepare and lead a mid-week Bible study group, do some further study, and have a network of friends.

Leoni graduated in science with first-class honours from Sydney University. She forwent a potential career in academia to become a missionary mum. Many missionaries going for shorter terms (for say up to ten years) can often pick up from near where they left off, but there comes a time when you know there is, realistically, no way back!

Often the most heartfelt cost is borne by other family members, especially those close to us. My parents only saw our children every three or four years when we came back on six-month home assignments. Now our adult children have returned to Australia without the large network of friends that most of us developed in our school years. Most of their school friends from Cambodia returned to their own passport countries within a week of graduation.

While our sending agency has taken good care of us, and we have benefited from God’s protecting hand through times of peril (and our own foolishness), we have witnessed other missionaries face medical emergencies that would be easily handled in Australia (dengue fever, traffic accidents with no ambulance available, food poisoning), individuals burn out from the pressures of work and life in an alien environment, and we have seen marriages break up in an environment filled with temptation. Then there is the presence of the sexual abuse of vulnerable people, modern-day slavery sanctioned by local authorities, and the grinding mental anguish of living among the very poor.

So why bother? Is the cost of taking a family from a great place like Australia into the undeveloped world still worthwhile? Aren’t there plenty of opportunities for Christian service in (almost wrote “godforsaken”) Australia? Why not just go for a short time so we can experience cross-cultural life, be identified as missionaries, make some foreign friends and gain new life experiences, but then leave before we face any serious costs that threaten to permanently scar us, our family, or put an end to normal Australian life ambitions?Speaking from the other side, if 20 years is long-term (I have some distant relatives who are just about to return to the UK after completing more than 55 years of service in Thailand), the real benefits of missionary service come from long-term service. I am not speaking about the benefits that accrue to us, but to the people and the Church that we seek to serve. At the end of each term, we leave Cambodia feeling that we have been that much more effective in our work than the previous term, but also with the sinking feeling that there is so much more we need to understand in order to become truly effective.

There are many aspects to learning a foreign culture. As we become more familiar with some aspects, others begin to emerge into our field of vision. Cambodia is a place where the “patron-client” system operates, and churches often just repeat this pattern with a Christian veneer. Like many other cultures, this is an “honour-shame” culture, where people are generally primarily motivated by avoiding shame and seeking after honour. When they encounter the gospel, they enter into a new understanding of shame (and who bore the ultimate shame), and the object of their primary honour should now be directed away from idols (or people) towards God. The temptation is to merely move this honour to the messenger, whether that be the pastor or the missionary. Our students are often motivated by a survival mentality, parental fealty, post-traumatic stress, the presence of the spirit world and a host of other dominating influences that we did not imagine and certainly not comprehend in 2001.

Language acquisition is (or should be) an endless process. We have always found that our communication and effectiveness are limited by our understanding of technical vocabulary, slang, or sayings. At first language learning is 90 per cent perspiration and 10 per cent inspiration. We open our mouths to communicate and people laugh (and they sometimes still do). Even Western missionaries experience shame at this point, and many begin to clam up, resorting to local interpreters for official communication. Long-term missionaries need to endure, persevere and continue to learn more and more if they are to see tangible benefits from the grind of daily language learning.

As with much learning, it does become more interesting and rewarding, as we not only communicate but begin to comprehend its nuances (such as people literally say one thing but mean something quite different). If we use an interpreter or translator to teach and prepare our lessons, our communication is limited by their understanding of the subject. If we are grappling first-hand with the language, we are encountering the challenges our students face. We are then in a better position to equip them to learn. The Khmer Bible is at places quite different from the English Bible (and this too depends on which version you are using). The students might appear appreciative of our efforts, but inside they are puzzled but don’t want to bother or dishonour the foreign teacher with questions revealing their ignorance.

When I was a new missionary, I was quickly surrounded by lots of local friends and received lots of invitations to preach and teach. Only much later did I realise that these people had found me, and were drawing me (a potentially rich patron) into their agendas, generally by making me aware of some urgent financial need: “Our church would be so much more comfortable if we had air-conditioning!”. However, these invitations soon ceased.

As we have become more culturally savvy, we began to initiate our contacts with local people, and so set the parameters of relationships. Rather than being potential patrons, we seek to come more as equal partners in the gospel. Where we are ambassadors, we want to be representing Christ’s kingdom, rather than representing a source of foreign funds. Despite our many language mistakes, cultural blundering, and disappearing at awkward times for home assignments, we now have hundreds of former students who continue to regard us warmly as “lokru” or “neakru” (teacher), as well as neighbours, market stall holders (where Leoni does the family shopping), cycling buddies, and work colleagues.

Measuring the impact of missionary service is never easy. Many return burnt out with a broken spirit, some bankrupt, or left with few family members and friends. Some are forced to leave their adopted country due to a change of government policy or regime, while others find ill health brings about a “premature” conclusion to their service. Sometimes we measure our impact by organisations set up, churches planted, numbers of converts, books published or any one of a number of other performance measures. However, I suspect that it will often be some passing conversation, the testimony of family life, some seemingly botched sermon, or a classroom lesson within a seemingly unimportant subject assigned to us, that the Spirit of God used to bring about a spiritual transformation in a local person, who will go on to be used by Him in mighty ways that we were never able to be used.

Finally, a question we are often asked is “How do you do it?” that is, “How did you manage to stay on the mission field for so long?” If I am in Cambodia, it is easier to joke and say that I am still saving up for an airline ticket home. Many people come with a long-term plan, but often through difficulty, and sometimes tragic circumstances, are forced to return prematurely. However, many others come ill-prepared and, dare I say, less committed than they ought to be.

Almost every missionary term, we have faced some major crisis that threatened to take us from the field. This has included having to defend ourselves in a court of law, the birth of a disabled child (our daughter was born with a bilateral cleft palate, and so could not feed herself), the tearing apart of a Bible college I was teaching at, seeking to manage anxiety and exhaustion, death of students who were close to us, and leaving our son in Australia only to have a worldwide pandemic ruin our plans of regularly catching up with him.

My relatives (mentioned above) had to cope with the death of a child. By the grace of God, our daughter received surgery enabling her to lead a normal life, the court case was satisfactorily resolved, the Bible college continued under new leadership in a better direction, and with the opening of Australia’s borders, we are reunited with our son.

Missionary commitment does not come easily, and the costs are borne not just by the individual but by the wider family and the sending Christian community. However, if the missionary enterprise is deemed worthwhile, then long-term missionary service bears fruit that is the most likely to withstand the test of time.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?