Karina Brabham serves with the Church Missionary Society (CMS) in Poitiers, France, where she is involved in encouraging and equipping university students with the gospel of Christ as a staff worker with the Groupes Bibliques Universitaires (GBU).

“Does your church pray for evil spirits to be chased away?”

When I moved to France to work in student ministry, I knew I was crossing cultures and would have lots to learn about the French context.

Yet questions like the one above weren’t high on my list of what I expected students to ask. It’s come as a surprise to me just how cross-cultural ministry here has been.

The new year marks one year of my working in local student ministry with the Groupes Bibliques Universitaires (GBU) in the small city of Poitiers in France’s central west region. It’s been a big year of learning and continually being reminded how much I need and rely on God’s grace and power.

My assumption in preparing for the move to France as a missionary was that I’d need to understand the broader French cultural mindset and the laws around religious expression in public spaces, particularly the university setting. And while this has certainly been valuable as I’ve adapted to life and ministry here, it has not been as simple as that.

Student ministry is also international student ministry

One big realisation this past year has been the cultural diversity in the local student group at Poitiers, which is typical of many GBUs around the country. In France, close to half of foreign students come from Africa, and this statistic is clearly represented in the GBU at Poitiers. The group has representatives from the Ivory Coast, Gabon, Togo, Mauritius and Guinea, just to name a few places.

Unlike in Australia, where there is often a dedicated international student ministry that operates alongside the local student ministry, all these students are gathered together in the GBU.

Most African students studying in France come from francophone countries, so language isn’t often a barrier. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t barriers. While they may speak French, the culture they find themselves in can be bewilderingly foreign. The way things work in France isn’t always the way they are used to, and this includes church and ministry.

In talking with some Christian students from French-speaking Africa, it’s clear that what was normal for them back home is very different from the French mindset. Religion is a much more publicly expressed affair in their cultures and evangelism is more likely to look like soap-boxing in the street. Many don’t drink alcohol and can have a perspective approaching legalism on what it means to be a Christian. Spiritual forces are an accepted reality.

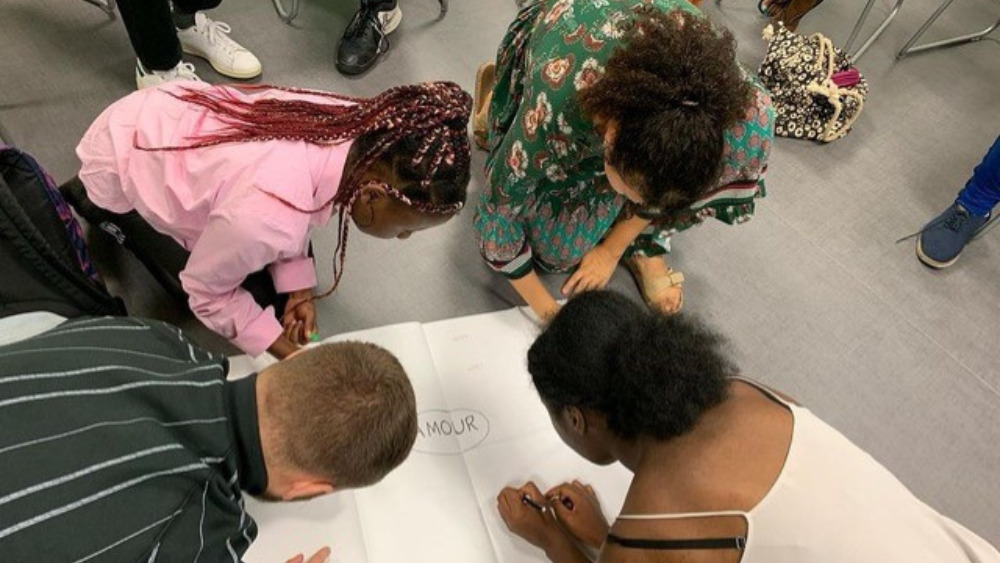

Karina Brabham leads a GBU Bible study in Poitiers, France.

In the past month, a student from Gabon has joined the GBU in Poitiers. After his second time coming along to a Bible discussion, he asked the question: “Why aren’t we praying?”. In our weekly get-togethers for the student group, we read and discuss a biblical text, but we don’t pray. For this student, opening the Bible without a time of prayer was strange (as I assume it would be for many Aussie Christians, too). The reason is shaped by the cultural and legal context in France.

First, according to the law, we aren’t allowed to pray as a student association meeting at the university. In France, universities are public spaces where religious worship activity (like prayer) is not permitted.

Secondly, we always want to present the GBU as a group where everyone is welcome to come and discover what the Bible says. While most of the students in the group are believers, the idea is to keep the group from becoming too insular. On a cultural level, praying is considered a private practice, so for many local non-believing students (who might be interested in investigating the Bible) it can be quite off-putting.

There’s lots of variety in church backgrounds among believing students …

One of the challenges I’ve come across this year is how to encourage students to be more welcoming to outsiders and avoid falling into the trap of making statements during a discussion that assume everyone is a like-minded Christian.

This is especially important as there’s lots of variety in church backgrounds among believing students. Conversations around what’s normal for them in their church experience are often illuminating (and give context to the student’s question above about praying about evil spirits).

Yet one of the joys has also been discipling these students. I’ve really loved getting to know them, learning about their cross-cultural experiences and helping them to see how the Bible speaks into their lives. I’m keen to keep encouraging students who want to publicly share their faith, but who find their “normal” ways of doing so are discordant with French culture.

For some, who have been in France for a few years, they have learned to censor themselves in social situations because of the reactions they received when openly talking about Jesus when they first arrived. They now have much more cultural awareness but need to regain some boldness for the gospel.

Even when I’m out of my depth in terms of cultural knowledge, the essential I can come back to is always the gospel.

The gospel is for every culture

“Go therefore and make disciples of all nations …” (Matthew 28:19). The great commission makes clear that Jesus desires people from all cultures to know him as their Lord and Saviour. The gospel is for people of all nations and the good news of Christ contains the answer to all their fears, needs and concerns.

I’m convinced of this, and I’m thankful that even when I’m out of my depth in terms of cultural knowledge, the essential I can come back to is always the gospel. I still have lots to learn about the nuances of different African cultures and the various church denominations students come from, but the gospel is always the truth they need to apply.

Whether it’s talking with a local French student about materialism or an African student who worries about a curse his witch doctor grandfather put on him, it all comes back to the gospel. And even when the practicalities of student ministry aren’t the same as those I knew in Australia, the gospel is still at the heart of the GBU in France.

While I’ve got lots to learn about the context I’m in and the complexities of the many cultures I’m crossing in seeking to share Christ and disciple students, I already have what’s essential. The gospel is the truth I need to keep meditating on and applying in every step of my cross-cultural ministry journey as I encourage the students I meet in France, wherever they may be from, to do the same.