Remembering the joy on Ambae Island

There will be no going home for the islanders of Ambae in Vanuatu who are being permanently evacuated.

Disaster has struck the volcanic island of Ambae, one of the northern islands of Vanuatu. Unthinkable tragedy has rendered their once-beautiful island home unliveable. On this island three years ago, the Havai New Testament was launched with great celebration and joy. Now the island is grey and lifeless.

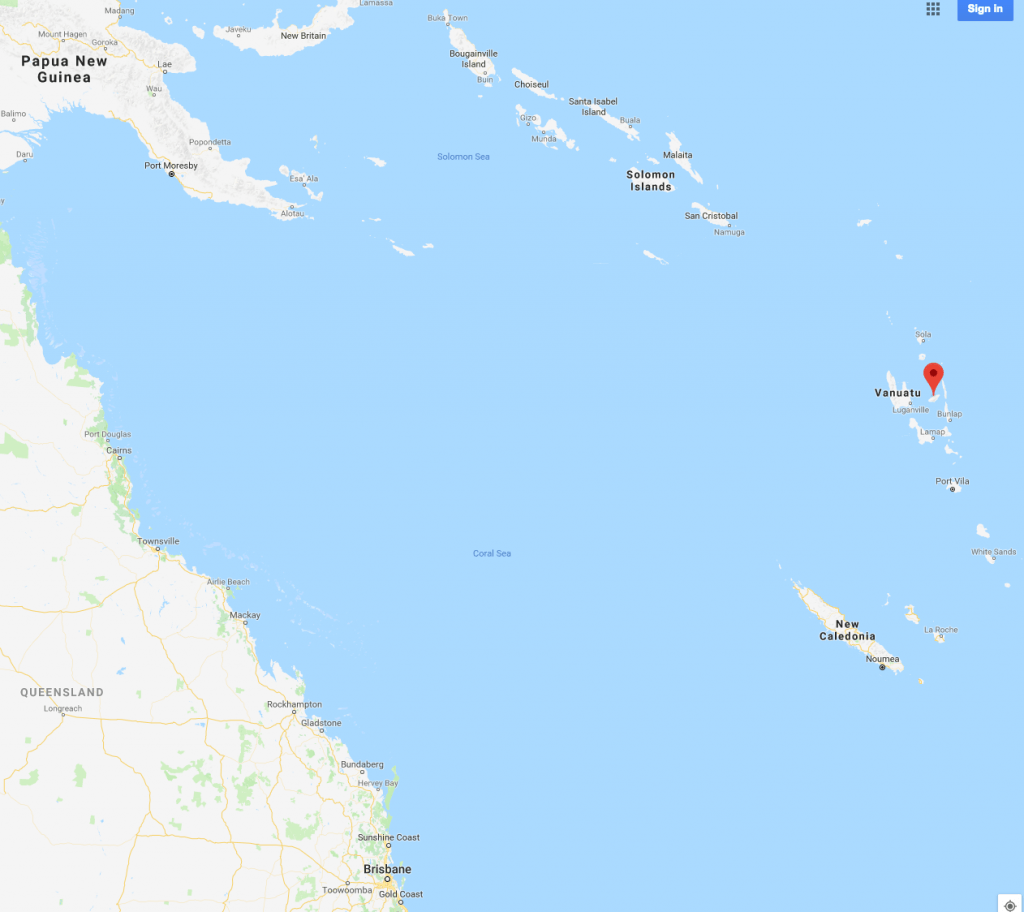

Ambae Island, also known as Aoba or Leper’s Island, is an island in the South Pacific island nation of Vanuatu. Google

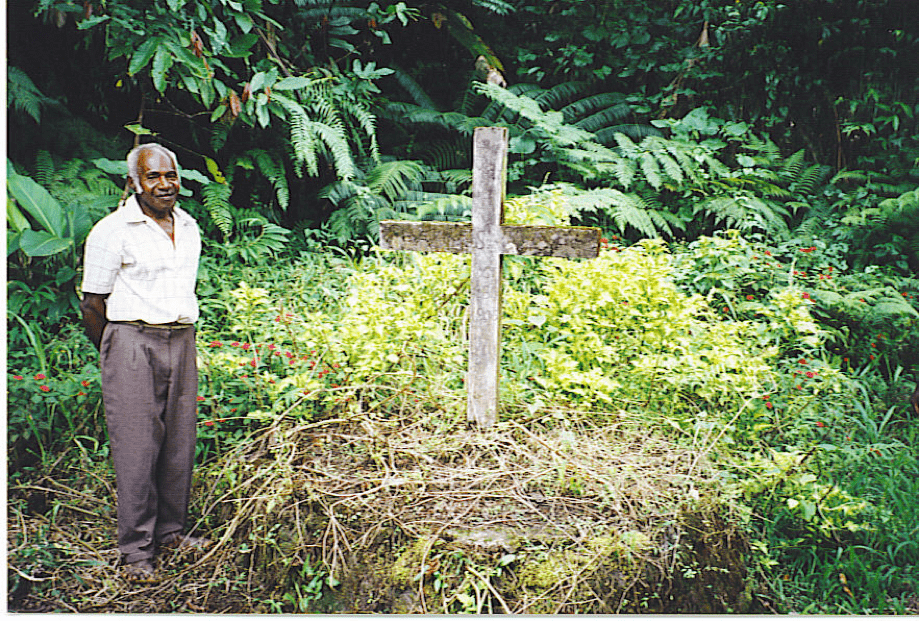

Christian missionaries first came to Ambae in the 1890s. People readily accepted the gospel and, within a generation, many people on the island were Christian. In 1906, Australian missionary Rev Charles Godden met his death there. He was killed by a violent man, angry at his humiliating treatment in Australia during the ‘blackbirding’ period of forced Pacific labour on the Queensland canefields, a shameful era in Australia of legalised slavery.

The cross in the jungle, the site of Charles Godden’s martyrdom. John Harris

Charles Godden is revered as a saint on Ambae. His martyrdom deeply affected the people and led to a deep and lasting commitment to peace. At the time of his death, he was beginning to translate the Gospels into the Havai, the language of the Lombaha people in the north-east of the island.

The ceremony to launch the Havai New Testament was one of the most deeply meaningful moments of my whole life.

Havai was a small language on a remote island. Subsequent missionaries lacked Charles’ enthusiasm for Bible translation. No one doubts the dedication of these early missionaries but, as so often happened on small Pacific missions, medical aid and schooling occupied the time and effort of the missionaries whose home societies did not encourage them to spend much time on local languages.

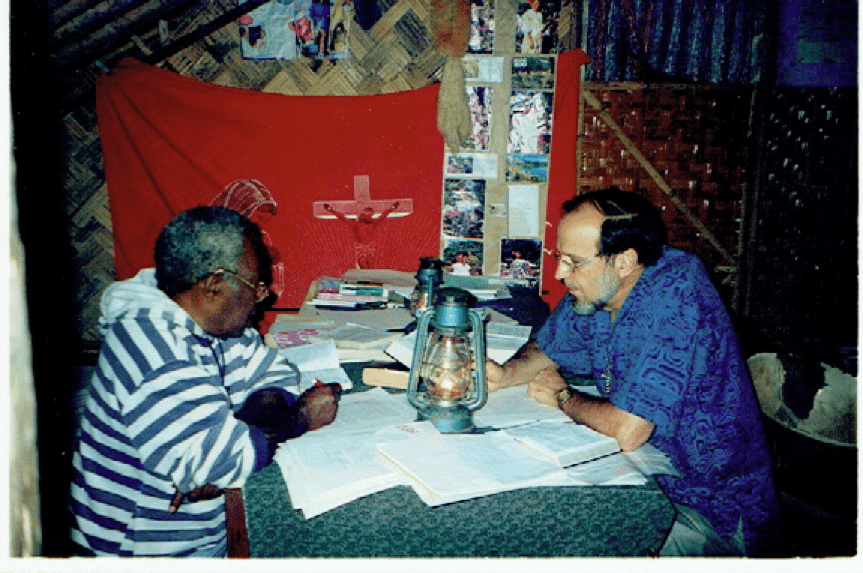

Joseph Mala and John Harris translating by the light of a hurricane lantern.

The Lombaha people’s enthusiasm for the Bible and their heart language did not wane. In 1994 a New Testament translation project commenced in the little village of Lolobivunge with Chief Joseph Mala and Rev Charles Tari as the main translators and myself, Rev Dr John Harris, as the Bible Society’s translation consultant to the project.

There was a very real danger that the mountain and the island of Ambae would explode in a shattering eruption.

The translation took 20 years to complete. This is true of most translation projects in languages like Havai where small groups of people subsist on the produce of their gardens in the jungle clearings. The local translators were all voluntary. They had to tend their crops, feed their pigs, construct their own houses from local materials and care for their families. Often the only time they found to work on Bible translation was late at night by candlelight or hurricane lantern.

The boys carrying the Havai Scriptures into St Christopher’s Church.

But in 2014 they completed the Charles Godden Memorial New Testament. It was a wonderful dedication ceremony.

The ceremony to launch the Havai New Testament was one of the most deeply meaningful moments of my whole life. High up in Lolobivunge Village where the translation had begun, the translators handed the new Havai New Testament to the Chiefs of Lombaha. Dressed in traditional chiefly costume, the chiefs carried the Scripture down through the jungle path to St Christopher’s church to the waiting crowd welcoming them with song. There an amazing thing happened. The chiefs handed the Bible to the teenagers, their gift to the next generation and it was they who carried the New Testament into the church.

Volcanic activity began to increase again, not the immediate peril of an explosion but the creeping menace of volcanic ash.

The joy of the people was unbounded. The book to be dedicated had to be quickly wrapped in plastic when the heavens opened and the warm tropic rain fell but nobody cared, nobody minded the showers of God’s blessing upon the occasion. The lonely death of Charles Godden on a jungle path a century before had not been in vain. The exuberant celebration continued long into the night.

And then the worst imaginable disaster struck.

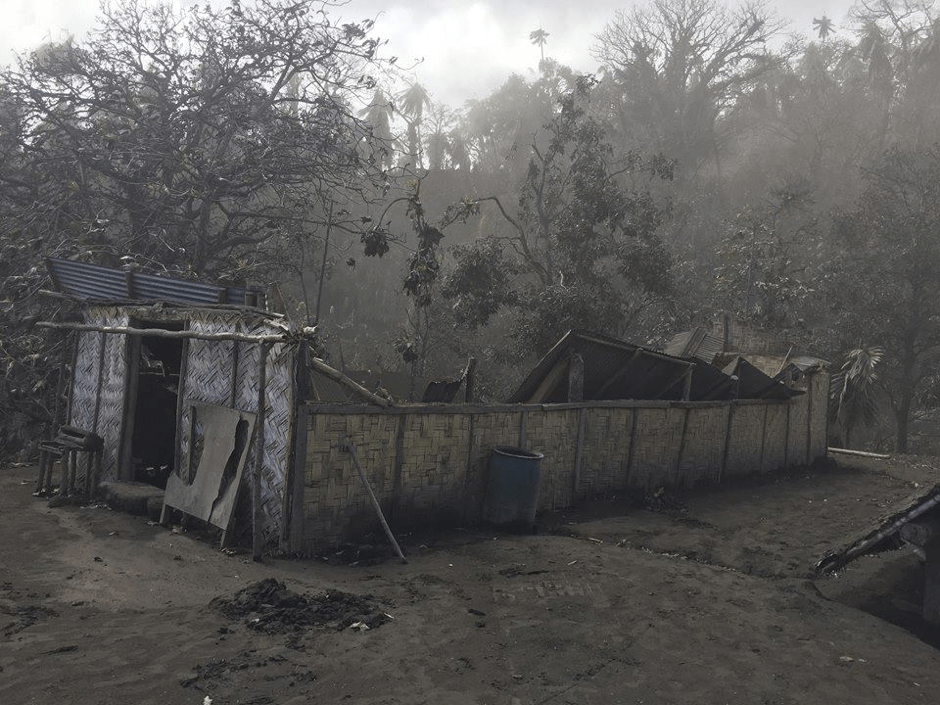

The island was greyed out with volcanic ash.

In September 2017, three years after the joyous celebration, the volcano at the centre of the island erupted. They call the volcano ‘Manaro’, the volcano which long ago built the island from the sea floor and the volcano which can destroy it. There was a very real danger that the mountain and the island of Ambae would explode in a shattering eruption. The Government of Vanuatu evacuated everybody from Ambae to nearby safe islands. This was a traumatic experience for the people, sailing away from villages and homes, from gardens and animals, perhaps never to return.

In mid-April the Government of Vanuatu announced the urgent, total and permanent evacuation of the island. All people were to leave the island for ever by 1st May.

But after a few weeks, the danger of an explosive eruption subsided. The people were allowed to return to the island. By December, most of the island’s 11,000 people had come back home. But everything was not right. The water had an unpleasant taste and the vegetables in their gardens were shrivelling. Even the jungle did not look right, the leaves drooping and greyish.

In March 2018, volcanic activity began to increase again, not the immediate peril of an explosion but the creeping menace of volcanic ash. There was no sound, just the smoke by day and the fire by night and the incessant silent fall of ash, blanketing the ground, poisoning the gardens, contaminating the water, smothering the jungle and overwhelming the people.

It was as if the very heart had been torn out of the community.

Village and forest became totally greyed out. The thatched roofs of the houses buckled and caved in under the weight of ash. Early in April, watched by grieving people fearful for their own survival, the iron roof of St Christopher’s Church finally fell under the weight of ash.

St Christopher’s Church collapsing under the weight of volcanic ash.

It was as if the very heart had been torn out of the community.

In mid-April the Government of Vanuatu announced the urgent, total and permanent evacuation of the island. All people were to leave the island for ever by 1st May.

The Government has begun negotiations with communities on other islands to secure land to build new villages and resettle the people. It is the only possible course of action. But it will take some years. In the meantime, the poor nation of Vanuatu will try to provide temporary accommodation, basic food and shelter for a displaced people.

It is not easy for the Christian people of Ambae to sense God’s hand in their terrible situation today.

These are a Christian people. It is deceptively easy for those of us comfortable Christians in more affluent and safer communities to speak of faith and hope and God’s protection. But in the ashes of their communities and homes, it is not so easy to feel the presence of God. Psalm 46 declares,

God is our refuge and strength, an ever-present help in trouble. Therefore we will not fear, though the earth give way and the mountains fall…

This is a deep and abiding truth. But it is not easy for the Christian people of Ambae to sense God’s hand in their terrible situation today. God has not deserted them but that is how they feel. Please pray for the people of Ambae that they may come to see this in the midst of such grief and so great a tragedy.

Rev Dr John Harris is a Bible Society translation consultant, and worked with the Ambae people on the Havai New Testament for over 20 years.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?