The remote Aboriginal community of Wadeye, about 400km south of Darwin, has been in the news for all the wrong reasons this year. Months of unrest and violence between rival families have led to severe property damage, dozens of arrests and the displacement of up to 500 people.

The tensions even led to the postponement – twice – of the launch of the Murrinhpatha Mini-Bible, which was printed last year.

But there is another side of the coin that reveals a much happier picture of the community once known as Port Keats, which was set up as a Catholic mission in 1935.

The Catholic community school – Our Lady of the Sacred Heart (OLSH) Thamarrurr Catholic College – has successfully fought against all government attempts to dismantle bilingual education across the Northern Territory. Its Murrinhpatha literacy program introduces English in a stepped fashion from preschool to secondary level, allowing children to move from the known to the unknown and achieve academic goals without destroying their language and identity.

And what’s interesting from a Christian point of view is that the Murrinhpatha language, culture and religion are woven together in the same classes at the school.

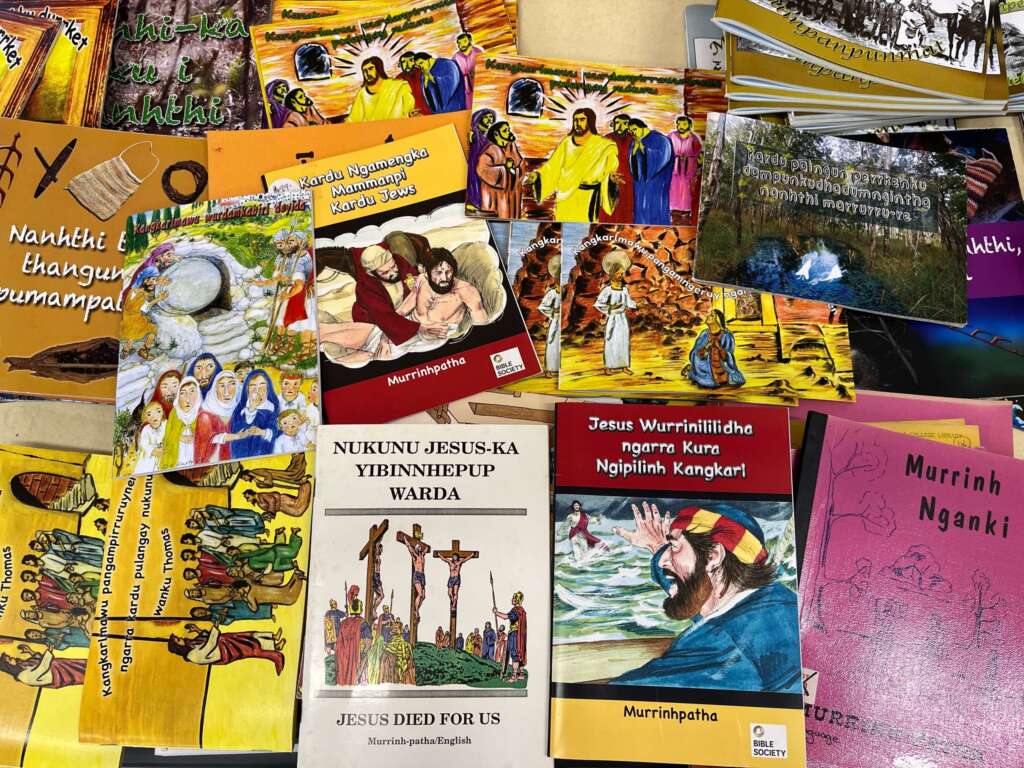

“Many of the resources produced to teach kids in Murrinhpatha are actually Christian stories or gospel stories, so in the classes, language and culture and faith are all mixed together,” says Ben van Gelderen, principal of Nungalinya College in Darwin, where a group of long-term bilingual workers from Wadeye are studying a Murrinhpatha course, to develop their confidence in reading and writing their own language for future translation work.

An array of educational resources are still being produced in Murrinhpatha.

“It’s deep in our heart that we are wanting our kids to have a better and a good life in the future,” says Gemma Alanga Nganbe, who has been teaching the bilingual literacy program at OLSH Thamarrurr College Wadeye since the mid-80s.

“We just want to do the best we can while we’re here so we can support our kids to have good education in school and out bush.” – Gemma Alanga Nganbe

She began, she explains, as a “flagpole at the back of the classroom” in 1977, graduating from scrubbing floors, sweeping and sharpening pencils to team teaching in the early 80s, then training through Remote Area Teacher Education (RATE) in 1984.

“In the late-80s, Indigenous people started writing about their schools that we want both-ways education. We wanted to be bilingual. We wanted to be bicultural. And really, that was the heyday with lots of positives,” Alanga says.

“We just want to do the best we can while we’re here so we can support our kids to have good education in school and out bush – ‘both ways education.’”

Meanwhile, the Albanese government has recognised the importance of teaching First Nations languages by announcing it will train and hire ‘First Nations Educators’ to be placed in 60 primary schools across the country from semester two, 2023.

A federal Education Department spokesperson told Eternity $14 million will be committed towards implementation of the plan. First Nations communities will work with state and territory governments and school systems to select the 60 schools to participate, with priority to be given to schools with high enrolments of First Nations students.

The tug of war over bilingual education in the Northern Territory has been going on for nearly half a century – ever since the Whitlam government introduced it during its first days in office in December 1972 as part of sweeping reforms in Aboriginal affairs.

While bilingual education costs more – with the hiring of a teacher-linguist and funding of a Literature Production Centre – bilingual programs were considered the best route to mastery of English as a second language.

Support for it waxed and waned over the years, with its heyday in the mid-1980s. The Nungalinya library contains many beautiful booklets and readers from that era in numerous Indigenous languages.

A 2009 Four Corners documentary focusing on bilingual education and the future of the Warlpiri language, Going Back to Lajamanu, documented a modest but steady improvement in English literacy at the school in Lajamanu, in central Australia, in the 1980s.

Sadly, bilingual education was politically unpopular in the Country Liberal Party, which governed the Northern Territory from 1974 to 2001. Lajamanu’s bilingual program was one of many that fell victim to the CLP’s view that bilingual education was not only expensive but unnecessary.

It was a view still being prosecuted in 2009 by Gary Barnes, the head of the NT Education Department. “We absolutely want our young Indigenous people to become proficient in the use of the English language. It’s the language of learning. It’s the language of living and it’s the language of the main culture,” he said in the Four Corners documentary.

The death knell for bilingual education was sounded in 2008 when the first NAPLAN tests showed that four out of five children in our remotest schools did not meet basic standards for English literacy.

“The [NT] government has been strangling bilingual education by defunding it for a long time.” – Ben Van Gelderen

A shocked Marion Scrymgour, the then the NT government’s education minister, brought in – overnight – compulsory teaching in English for the first four hours of each school day, leaving only one sleepy hour in the afternoon for Indigenous culture and language.

While that hardline policy has since been eased, the current NT Education Department guidelines on bilingual education are confusing and muddled – probably purposely, according to Ben Van Gelderen.

“Now, they did wind back first four hours in English policy after a big outcry, but the government has been strangling bilingual education by defunding it for a long time,” he says.

“So you were left with certain communities essentially saying, ‘Well, over our dead body, we’re going to carry on anyway. We’re a Department of Education school, but we don’t care, we’re going to still run bilingual education,’ but very few have the strength and audacity to do that.”

In practice, only about nine communities are still committed to the bilingual education model – notably Wadeye and, to a lesser extent, on the Tiwi Islands, he says.

The Murrinhpatha First Languages class leads chapel at Nungalinya College on the Tower of Babel.

Because Wadeye’s school was in the Catholic system rather than a government school, it was able to resist pressure to go with the new philosophy. Thankfully, Catholic Education agreed to continue to fund the production of all kinds of booklets and readers in Murrinhpatha, the most widely understood local language.

“There were some really strong leaders, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous – the non-Indigenous were usually Sisters who’d been there since 1973 – and they were saying ‘we are not caving in, we know what works,’” explains Van Gelderen.

“It doesn’t mean everyone in Wadeye is suddenly more literate than other areas because attendance is still a huge issue, and you can’t become literate in any language unless you go to school. But they held firm – ‘We know from what the elders tell us, from global research, that respecting language is educationally the right way.’ So they stuck to their guns.”

“If you learn to read in your own language, you will transfer much quicker to any other language, but you’re not bi-literate by Year 3.” – Ben Van Gelderen

Alanga credits Wadeye’s ability to continue bilingual education to honesty, strength, and the support of tribal elders, who agreed to focus on just one language, Murrinhpatha, despite their many other dialects.

“It was a great opportunity – it’s like a door that’s open to a new life. And it was really, really, really great. We were so lucky.”

The philosophy is to build children’s oral proficiency in their first language and then gradually introduce reading and writing in English in a stepped format. In the first school year, 90 per cent of learning is in their own language, which reduces to 80 per cent the next year, with 20 per cent in largely oral English.

“So you might not actually get to reading and writing English till Year 2 or Year 3,” explains Van Gelderen. “So, by stepping it, it’s increasing the amount of English as you go up. And the philosophy, which is proven across the world, is that if you learn to read in your own language, you will transfer much quicker to any other language, but you’re not bi-literate by Year 3. You’ve only just started looking at English texts in written form.”

As for the NAPLAN issue, the Wadeye teachers know their literacy results can’t magically improve by Year 3 – they take a long-term view, knowing that students don’t become genuinely bi-literate until their mid-teens.

“So instead of talking about the bad story of Wadeye, we have a school that just didn’t cave in, and the faith side is woven into it. And so it’s identity formation – we want our people to be Murrinhpatha people, and Christian, Catholic people and know their language. That’s the way it should be, so that’s what they’re doing. That doesn’t mean if you went down to Wadeye school, you wouldn’t go, ‘Oh, this is a complex and at some points dysfunctional place.’ There are many other factors, but they’re right in saying, ‘This is part of the good.’”

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?