Tom Slockee was sitting in the sun at home on the south coast of NSW, opening a bucket of oysters, when a bloke came up his driveway and said, “Tom, we need you to come to Sydney. The Minister for Housing wants to start an Aboriginal Housing Development Committee and they want you to be part of it.”

So continued Tom’s long career fighting for secure and affordable housing for Aboriginal people across the state and the nation, for which he was recognised with a nomination for this year’s National NAIDOC Male Elder Award.

Tom had felt the call of God on his life to improve access to secure and affordable housing for Aboriginal people, especially in regional areas, ever since he struggled to find a home for his family after leaving the Australian Army in 1983.

“We went to my wife’s country in Batemans Bay, Walbunja Country. That’s where the kids wanted to go – we had four boys. I had some super from the Army, but I couldn’t rent a house. We ended up moving into a condemned house with my sister,” recalls Tom, whose grandfather was a slave taken from Tanna in Vanuatu and who grew up in an Aboriginal community in Tweed Heads (Minjungbal).

“Every time I went to buy a block, they had it taken off the market.”

Eventually, a local Anglican church member housed the family in an old timber cottage that wasn’t connected to the sewerage, so Tom tried to buy a block of land to build a house on.

“But every time I went to buy a block, they had it taken off the market. I thought, ‘This is very strange.’”

Brushing off the racism as someone else’s problem, Tom asked for God’s help and forged ahead with starting an Aboriginal housing company with his wife, Muriel.

“Under the self-determination of those days, some funds were around for community organisations for housing. So we accessed some money and started buying houses for our community, which basically got me into Aboriginal housing.”

“It was sad that, in those days, we still had this anti-feeling about Aboriginal people in Parliament.”

The day he and Muriel were enjoying that feed of oysters in the sun, Tom had been planning to take a break from his work in housing. But Tom responded to the call from then Housing Minister Craig Knowles to join and lead the influential Aboriginal Housing Development committee, which led to the development and eventual passing of the NSW Aboriginal Housing Act 1998.

“It was sad that, in those days, we still had this anti-feeling about Aboriginal people in Parliament and my job was to sit in Parliament and win the Greens and other parties in the upper house. My job was to go and communicate with them why we are doing it, what the plans were and the strategy for the future. People find it hard to believe, but the greatest support was from Reverend Fred Nile – he supported us to the core. The Liberals opposed it, but it got through and we set up the NSW Aboriginal Housing Office.”

Through his leadership, the Aboriginal Housing Office promoted a new regional model to support smaller, community-focused Aboriginal housing organisations.

Through his leadership, the Aboriginal Housing Office promoted a new regional model to support smaller, community-focused Aboriginal housing organisations.

Tom had been developing his advocacy and leadership skills while working as an electoral officer for Pastor Uncle Ossie Cruse, then a member of the National Aboriginal Conference, which Tom describes as like a voice to parliament.

“I used to go to all the different communities from Wollongong to Kiama, all down the south coast to Bega and Eden. I would see what the need was and try to get that need met. I’d advocate for them, write submissions for them, help them set up organisations, get funding for administration, for housing, social issues – what the voice is trying to do now,” he says.

“It was a great job that God had planted in front of me so that I would get to know these people and these leaders in the communities. And I helped them with many things over the years.”

“I call it the holiest church on the south coast of NSW because … it had a lot of holes in it!”

At the same time, Tom found himself reviving a disused Anglican church in Mogo and building it up into the Boomerang Meeting Place.

“While looking for a house, we drove down the road from out of Batemans Bay, 10km kilometres south, to a town called Mogo. There’s an Aboriginal community there. As we drive down the road, we see this church that had been disused and knocked around.

“Muriel said, ‘Let’s stop and pray that church gets restarted again.’ I call it the holiest church on the south coast of NSW because it was an old fibro church and disused, and the kids used it as target practice with stones and rocks, so it had a lot of holes in it!

“Anyway, we stopped there and prayed that God would rebuild the church at Mogo. Of course, when you pray and ask God for something, he will always use you to answer that prayer. So, of course, we were prompted to go and do something about it.”

“When you pray and ask God for something, he will always use you to answer that prayer.”

After rebuilding the church and starting Sunday services and Sunday school, Tom persuaded the Anglican church to give ownership of the land back to the Aboriginal people. Tom went on to become an ordained minister in the Anglican church.

“These were some of the best days for certain in that little church in Mogo. The people would come, the kids would come, we’d have Sunday school, and we had an influence over the whole community,” he recalls.

“But then, the church got burnt down. From that, I believe God raised something better out of the ashes like he always does. That prompted us to build another church. We called ourselves Boomerang Meeting Place. Why Boomerang? It’s from Isaiah, where ‘My word that goes forth from my mouth shall not return void.’ It was the idea that the Creator shapes the boomerang so that when you launch the boomerang, it will take its life journey and circle and return to the one who made it. It was this whole idea that God created you, you live your life, and you come back to God.

“We rebuilt a residence on top and a meeting place underneath. I designed it not to look like a church but like a place that anyone could enter. Kids started using it, we had women’s groups and things were happening in the place and people coming and going all the time. We used to have youth groups and Sunday services there. That was one of the better times in my walk with Jesus.”

Tom’s life changed radically during his last year in the Army. He had been brought up in a Christian family and made a commitment as a child, but after his father died suddenly of a heart attack when Tom was 15, he had to go out to work and he drifted away from God.

I thought, ‘I need to change my life. I’ve got these four boys and I want them to grow up with some example of living better.’”

After the Army posted him to Melbourne, Muriel would take the kids to Sunday school at an Aboriginal Evangelical Fellowship Church in Fitzroy. But Tom would just sit in the car and read the paper. Then one day, he went to a rally with the South Australian Aboriginal evangelist Ben Mason, mainly to encourage his wife, who would give her testimony. But after the sermon, as people were singing old gospel songs, Tom heard the invitation to go forward and give his life to the Lord.

“I’m thinking, ‘I’m not living my life properly. I’m drinking and gambling.’ I wasn’t a bad person, but things just didn’t seem right because I couldn’t stop doing the things I didn’t want to do. And I thought, ‘I need to change my life. I’ve got these four boys and I want them to grow up with some example of living better.’”

But as Tom decided to go up the front, his feet wouldn’t leave the ground – they felt stuck like concrete.

“It was like a struggle between the Devil and Jesus about my life. I didn’t know it then, but that’s what I put it down to now. It felt like forever I was having this fight going on. ‘Will I go up?’ I tried to get my feet off the ground and go forward but I wouldn’t move. When I said, ‘I’ve had it, I give up,’ it was as if I just floated. My feet came off the ground as if I was transported to the front.

“It was amazing. That night I thought there were hundreds of people around me who had all come up the front to give their life to Jesus. I was told later that I was the only one up there. The old Aboriginal Evangelical Fellowship fellows said, ‘You had angels all around you.’ That changed my life.”

“My feet came off the ground as if I was transported to the front.”

Tom continues to be actively involved in the housing sector because he finds it hard to attract younger Aboriginal people, who prefer to work in other social sectors, such as health, education, and employment, which get direct funding.

As chairperson and director of two new peak bodies, the NSW Aboriginal Community Housing Industry Association and the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Housing NATSIHA, Tom wants to engage with governments to ensure that any housing and homelessness package includes a component for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander housing.

“Housing was a big need back for Aboriginal people when I started and there’s still a big need. Even in traditional days, where people gathered as family, a home was always important. Everyone needs a home to launch their lives from and bring up their kids. If you want to have good health, good education, and prospects of employment, then you’ve got to have a good home to come from. You’ve got to have a secure place,” he reflects.

Asked for his prayer points, Tom says: “Pray for strength and that God will impact younger people to come to know Jesus Christ as their Lord and Saviour. To know that when they are doing something, they’re serving a bigger cause – they’re serving God and their people through that. My prayer is for each community that God would raise up young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders to take responsibility and take up their roles with the support of elders. They would provide a great basis for these services that Aboriginal people need to be well-managed and well-governed.”

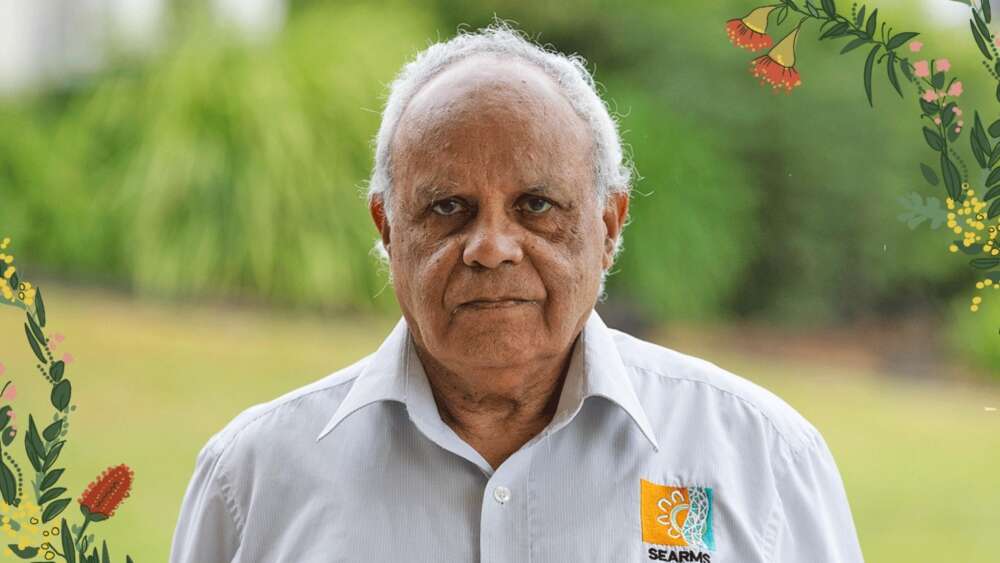

Uncle Tom Slockee is writing a book about the 20-year history of Southeast Aboriginal Regional Management Services (SEARMS) which he set up to manage housing on behalf of land councils and other Aboriginal corporations.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?