Catholics say Australia can pioneer eradicating slavery

Sydney QC John McCarthy believes Australia can be at the forefront of eradicating human slavery and forced labour from the world within a generation.

And he believes the Catholic church – one of the top-six procurers of goods and services in the country – will play a big part in achieving that goal.

The chair of the Catholic Archdiocese of Sydney anti-slavery taskforce says about 50 Catholic entities are preparing plans and programs to rid their supply chains, worth billions of dollars, of any connection with slavery or forced labour. They include schools, universities, hospitals and welfare services.

Australia “could be the first country in the world that substantially slavery-proofs its supply chains.” – John McCarthy

These programs will encompass tendering, pre-purchasing arrangements with suppliers, training of employees, and contract terms and clauses.

As part of Australia’s new Modern Slavery Act – passed in December last year – entities are required to identify and address modern slavery risks in their operations and supply chains. Unlike the British Modern Slavery Act, the Australian version encompasses the public sector and non-profit sector as well as the corporate sector. This is why McCarthy believes Australia “could be the first country in the world that substantially slavery-proofs its supply chains.”

“We’re supposed to be working to eradicate modern slavery and human trafficking in this generation.” – John McCarthy

The recent Eradicating Modern Slavery from Catholic Supply Chains conference in Sydney was presented with an analysis of the gaps in internal systems and processes of 32 Catholic entitles in various sectors with a combined spend of more than $2 billion. The results are in its progress report.

The key findings overall were that three-quarters of the reported spend had high potential risks for modern slavery and about half of the suppliers analysed were potentially high risk. In addition, 12 of the 23 categories of goods and services procured were deemed high risk.

McCarthy says the biggest shock for him was learning the very low percentage – less than 20 per cent – of Catholic entities that felt they were equipped to deal with the issue of modern slavery and forced labour.

“A similar percentage had no particular plans or programs in place, in relation to their suppliers, about this particular issue and how they would wish to deal with it. Nor did they presently have explicit programs in place, with respect to the preparation of contracts, the hiring of employees, and the training of employees and staff.”

About 50 entities have now been charged with getting “a serious program on foot” by the middle of next year. Six months later, they will need to present a modern slavery report. Both will need to reflect the organisational will to reorganise procurement procedures, not just complete “tick-a-box exercises”, he says.

“The guidance documents that were put out by the government make it clear that these are not to be speculative documents prepared by lawyers. You are reporting on what you are actually doing and you are required to assess what you are doing in terms of taking this out of your supply chains,” he says.

McCarthy says many participants in the conference had not been aware that, in September 2015, Australia and other nations had pledged to eradicate modern slavery and human trafficking by 2030.

“We’re supposed to be working to eradicate modern slavery and human trafficking in this generation. What the Holy Father wanted, and what this is all about, is that there is not another generation that is part of the shackling and the degradation of human dignity [of modern slavery], and the lack and loss of freedom and exploitation that comes with it,” he says.

“Saying you’re not going to do anything about it is saying there’s going to be another generation condemned.” – John McCarthy

McCarthy readily admits to being passionate about achieving this goal.

“I mean, the Pope says of this – ‘human trafficking is an open wound on the body of contemporary society, a scourge upon the body of Christ. It is a crime against humanity.’

“It is one of the great injustices of our world. But more than that… I was over in Connecticut where our third daughter lives, with her husband, in April. She had just had her third daughter. That little girl will never be a slave, but if we don’t work on it, there are little boys and girls who are born at the same time as her who may be fated for this terrible circumstance. So saying you’re not going to do anything about it is saying there’s going to be another generation condemned.”

The Catholic church has already introduced an ethical purchasing scheme.

As the largest employer of people outside of the public sector, the Catholic church is also in the top six procurers of goods and services in the country – larger than some states and territories.

There are 800,000 students in more than 1300 Catholic schools across Australia. In the Archdiocese of Sydney alone, there are 75,000 students in 153 schools with an expenditure of between $1.1 and $1.2 billion.

“Basically, the money is spent on salaries and wages. But in Sydney, expenditure on goods and services is somewhere between $150 and $200 million,” says McCarthy.

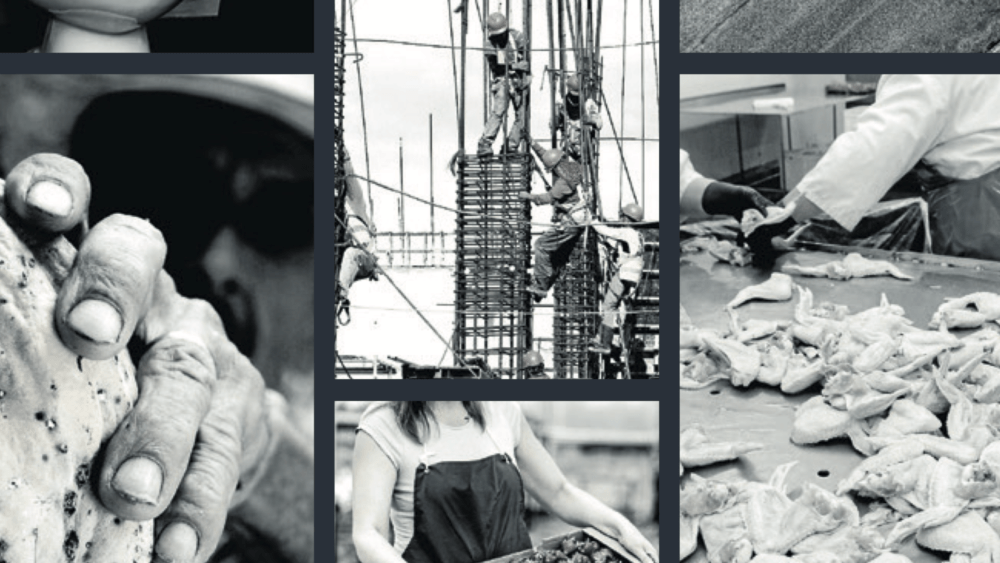

“About 70 per cent of Catholic expenditure on goods and services is in relation to construction – the building of schools or their renovation and extension. That brings into play the whole construction industry and all construction materials – much of which is imported from overseas.”

“A large number of uniforms worn at public and private schools (and elsewhere) have, in the past, been made from slave cotton.” – John McCarthy

Other major concerns relate to subcontracting cleaning services and the purchase of uniforms.

“There’s a whole range of things that have to be worked on. Australia is one of the great uniform-wearing countries in the world. Ninety-five per cent of uniforms are made in Asia, famously in India and Pakistan, and also in China. There’s a big issue around cotton from Uzbekistan and the way it’s picked using forced labour. It’s going to take some time to completely alter, but it seems that there’s a fair case for saying a large number of uniforms worn at public and private schools (and elsewhere) have, in the past, been made from slave cotton.”

“We’re going to take their money and their prestige away from them – that’s how this is going to end. ” – John McCarthy

While Sydney Catholic schools has an enormous procurement department, individual schools and parishes are responsible for buying uniforms. This means parents will have to be willing to pay more for uniforms in order to contribute to the anti-slavery cause.

McCarthy says International Labor Organisation figures show that modern slavery and human trafficking is a $150 billion industry.

“We’re going to take their money and their prestige away from them – that’s how this is going to end,” he declares.

“These people are cowards and if no one puts pressure on them they will continue to do these things. But if you take the money out of it, that’s the end of it.”

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?