Philip Yancey on not trusting his body, healing a 50-year family rift and what's so hard about grace

The bestselling author on the gift he didn’t want

Growing up in a strict, fundamentalist church in the southern US, a young Philip Yancey tended to view God as a scowling cosmic cop, “searching for anyone who might be having a good time – to squash them.” He later discovered that God’s grace comes free of charge to people who do not deserve it, even to him, who was “a single hardened link in a long chain of ungrace learned from family and church.”

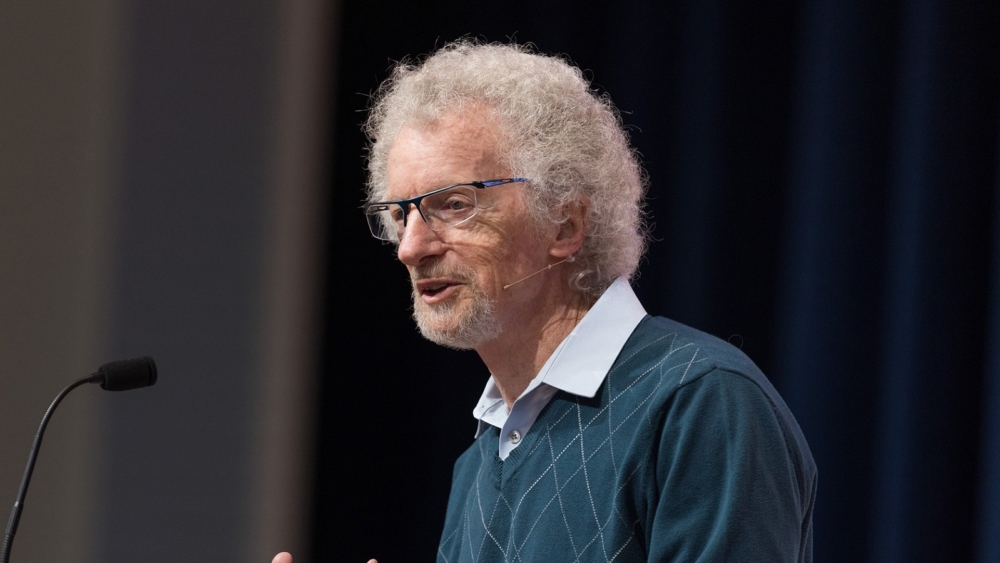

In this interview with Eternity on the eve of his 74th birthday, the bestselling Christian author reveals how his 2021 memoir healed a 50-year rift between his mother and brother, how he is grappling with his recent diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease, and why so many of his 25 books are titled with questions. Speaking from his home in Denver, Colorado, he talks candidly about the pain of his messy background and how it gave him a unique perspective to share the real Jesus with others who have been badly damaged by the church.

Eternity: You’ve been very busy lately, doing speaking tours of Canada and the US and sharing what you’ve learned from your messy background, your journey of faith, and how you’re coming to grips with your diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. So, how are you dealing with Parkinson’s?

It’s a daily habit, I suppose. I’m addicted to the medication. I have to take the pills four times a day, and if I don’t, I immediately start feeling shaky, a little buzzed in the head, and more uncoordinated than usual. At this point, it’s more an irritation than anything else where maybe I knock over a cup of coffee on the carpet or something like that, but compared to what it could be down the road and compared to what it is for some people, it can be very serious.

Philip Yancey

The thing is, in a nervous disease like that when it’s destroying your nerves, it only gets worse. It doesn’t get better because they die off and they don’t regenerate. And it also affects your entire body. So I started feeling pains in my toes that were operated on 30 years ago. I presume it’s either the medication or the Parkinson’s itself because strange messages are going through those pathways and the body will often respond to a strange message with pain, which is a good thing because we pay attention to it. But it does make me aware of how cognitive abilities could go, executive function … I figure I’ve got maybe 10 years of productive time left if everything keeps working as it is … So I need to choose what I do with my time carefully.

What’s been the most challenging thing for you? Has it been the disability or the change in your identity?

The most difficult thing for me is, is I’ve always been the master of my body. One year, I decided to run a marathon and went through all that learning. [My wife Janet and I] knew nothing about climbing mountains when we moved to Colorado. We’d lived in Chicago – we were city slickers. But eventually, my wife and I both ended up climbing the 54 highest mountains in Colorado. Each one is 4300 metres. So, I was used to beating my body into submission, and what I wanted it to do, it would eventually do. But now I can’t really depend on it.

It can be rebellious. It can be disobedient. And it’s a strange feeling not to be able to count on your body. I have not, to this point, started falling. That’s likely in the future. It’s certainly common among Parkinson’s people. I do balance exercises to prevent that, but it may happen, and it’s an uneasy feeling.

Philip Yancey skiing in Colorado. In 2022, while skiing, Yancey realised something was wrong when his legs refused to turn and he slammed into a tree.

I was amazed at how clearly and in what detail you recall your early years in your recent memoir, Where the Light Fell. I guess they were pretty unusual, growing up in a toxic church bubble.

Well, when you go through it, it seems totally normal. You think every family is like this; every church is like this. And only later did I realise these are some weird people over here – and I was one of them. But my first job was with a teenage magazine. All I had at that time was my first 21 years of life, and so I quickly wrote down everything I could remember about those years.

Then, later, I could go back with my brother, my uncle and my mother, and interview them about their own memories and try to put that together. So I consider it a gift, my life. It was not always pleasant; there were some hard parts, and people read it, and they say, “Oh, you were abused.” Well, I didn’t feel abused at the time. I just thought that that was life – you know, life includes pain. Now, it really did become a gift for me because all we writers have is, is our perspective. My perspective is different than yours and any other person in the world, and if it’s not different, you shouldn’t write – they don’t need you.

So I was given a unique [story] and I found that the extremes of my church, which was an angry, fundamentalist, racist, unhealthy, toxic church, that gives me the ability to say to people who are complaining and dissatisfied about their own church, “It’s actually worse than that – let me tell you my story.” And they would say, “Wait a minute, I thought you were a Christian writer.” And I say, “Well, I am, but it would be a bad trade to forfeit an opportunity to connect to the God who created everything because of the way the church treated you 30 years ago.” And it just gives me an entree.

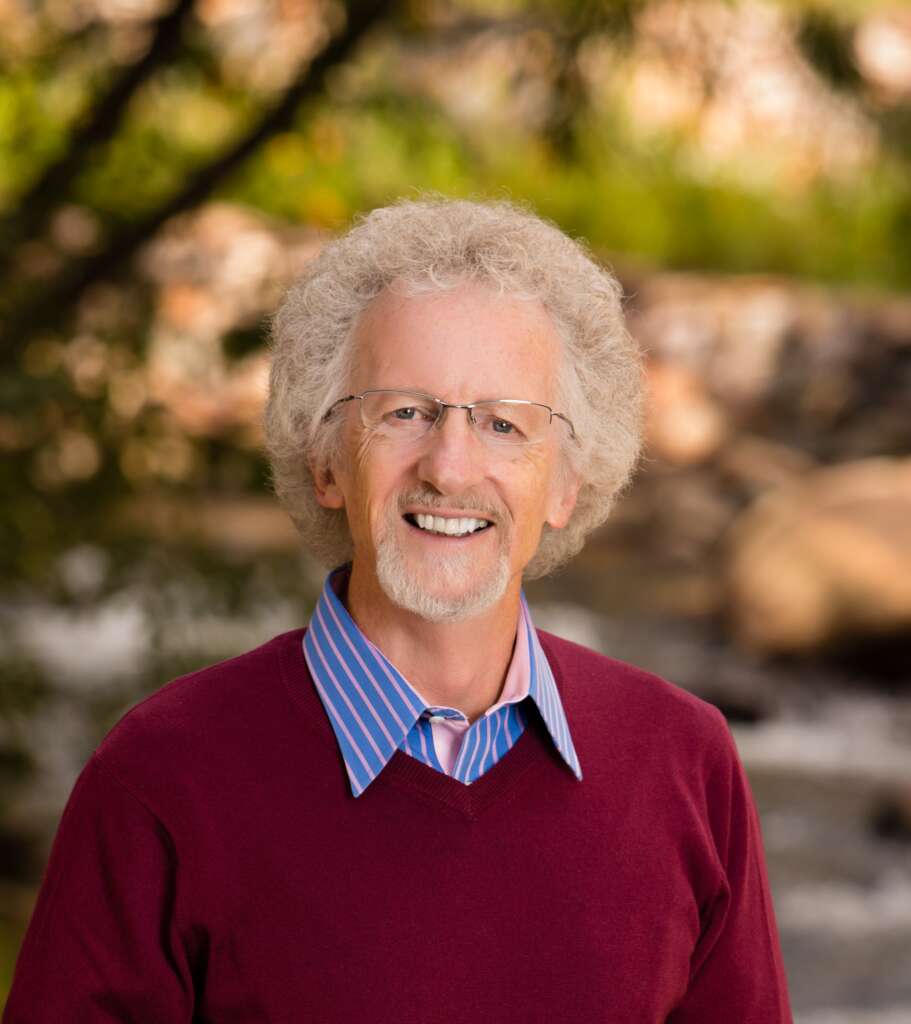

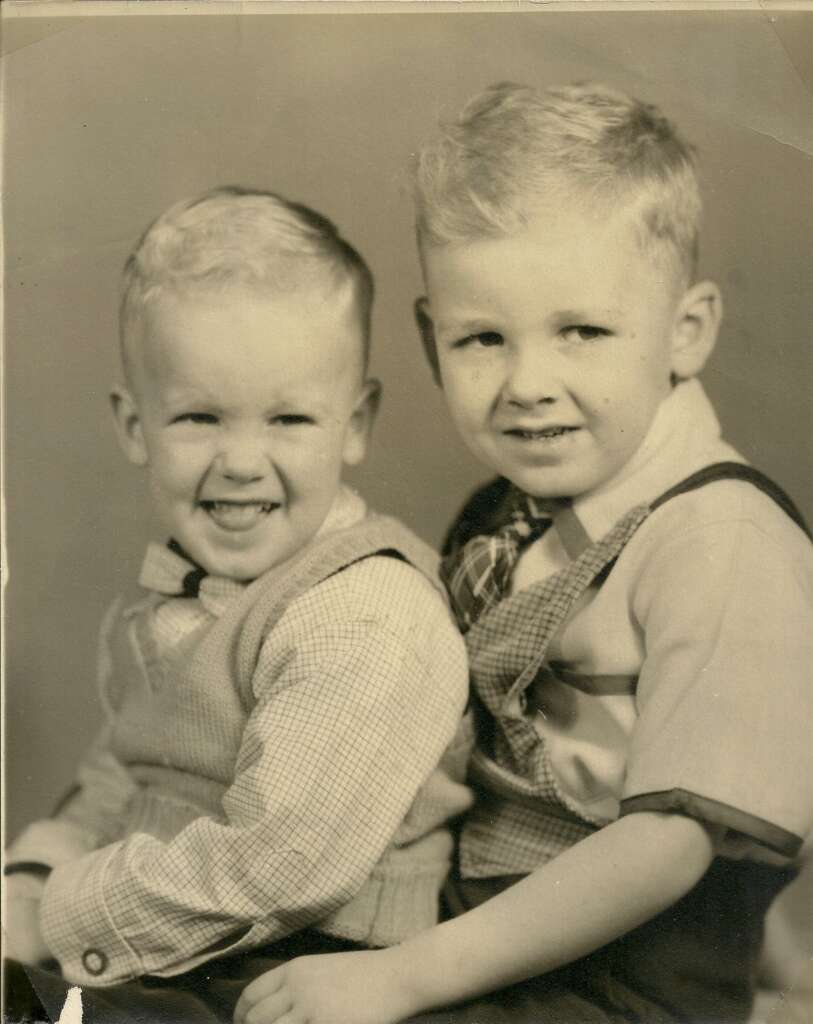

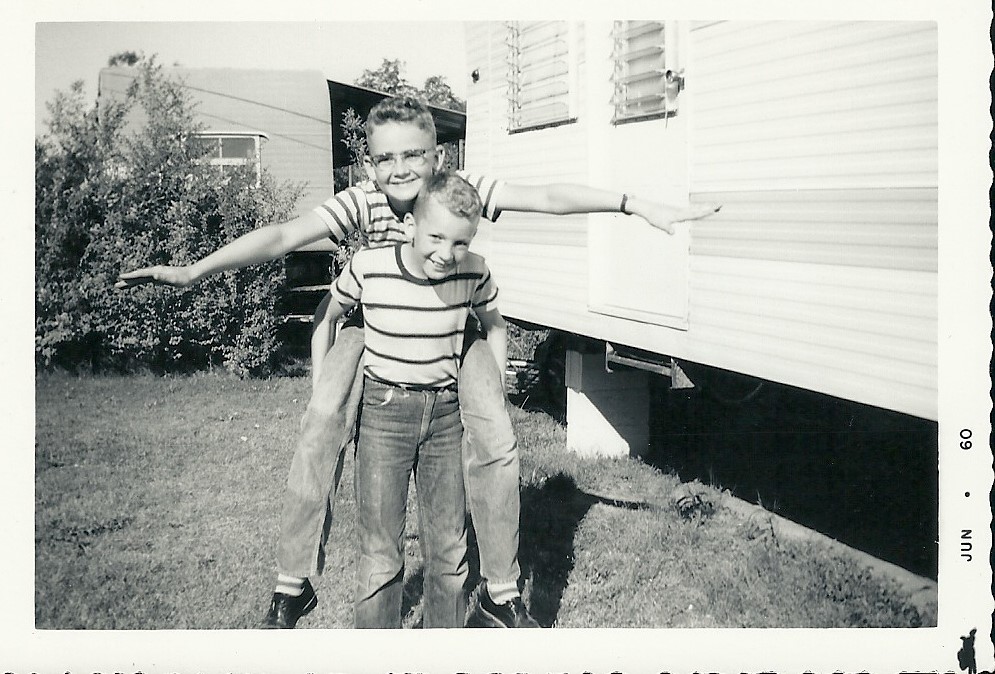

Philip and his elder brother Marshall.

You have acknowledged that not everybody likes your books, but that there’s a need for them among those who have had bruising experiences of church and haven’t encountered the real Jesus.

Yes. As long as you get the criticism from both sides, I feel okay. My wife likes to say you cast yourself as a bridge builder. And I try to do that on controversial issues and things like that. She said the problem with bridge builders is you get walked across from both directions. But what’s the alternative? A one-way bridge that just drops off into the ocean? I don’t like that one either.

Let’s have a look at the bombshell of your father’s death and how discovering that in your college years affected you.

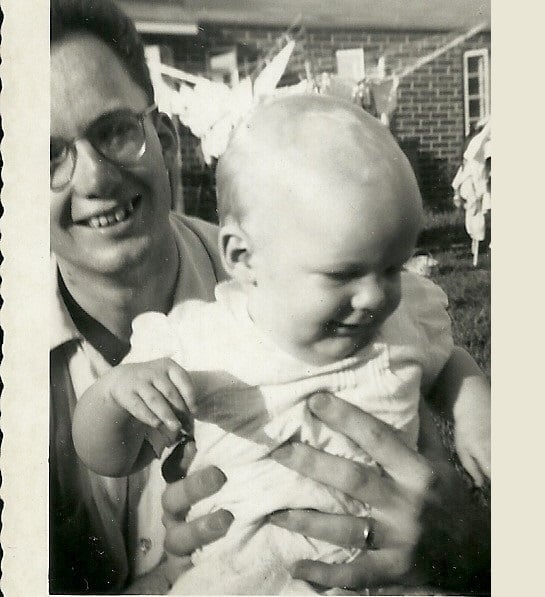

Well, my father’s death was the primary event of my early life. I was one year old when it happened, so I have no conscious memories of it. Of course, I knew he died. That was around us every day – there was no father in the house, never was. But I didn’t really know the story behind this story.

I knew that he had polio … he was 23 years old. And he went overnight from being totally healthy to being totally paralysed. So much so that he couldn’t even breathe on his own; his lungs weren’t strong enough. So he was put in this machine called an iron lung. You may have seen pictures. And the machine breathed for him. It was a miserable existence. He was in a charity hospital, the only one that had an iron lung in Atlanta at the time. And people wouldn’t come when he tried to call. He couldn’t even push a button to call the nurse. He was paralysed; he just lay there all day looking at the ceiling. There was no TV, he couldn’t read a book, nothing. He was planning to be a missionary. They had actually gone around and raised support. So they had several thousand people on a mailing list and they were getting ready to go to Africa with two young sons.

Philip with his father

And then suddenly, he’s in an iron lung, unable to move. So the Christians around him cared for him. Obviously, they wanted the best [for him], but they decided that it could not possibly be God’s will for God to take him at such an age with such a future in front of him. So they prayed and believed that he would be healed, and against all medical advice, eventually, they removed him from that iron lung, from that hospital. He showed a little bit of improvement, maybe for a few days, and then nine days later, he died. And I found that out, not from anybody telling me, but when I was a college student, by reading an old newspaper clipping from the main paper in Atlanta, the Atlanta Journal.

“My writing career really has been taking one part of doctrine, one question, one puzzle of theology at a time, picking them up, taking them apart.” – Philip Yancey

Secrets have power, don’t they? When the secret is out, it really has power. And one of the things I learned right away was not everybody who claims to speak for God does so. And that became a theme in my writing because, again, I grew up in a church that was blatantly racist, unashamedly racist. They believed it was doctrine – the Bible taught that people of colour were inferior. Later, I found out they were wrong. Not everyone who claims to speak for God does so.

So my writing career really has been taking one part of doctrine, one question, one puzzle of theology at a time, picking them up, taking them apart, going to some people that I trust, and then figuring out what I can stand behind. That’s why so many of my books start with questions. Where is God When it Hurts?, Prayer: Does it Make any Difference?, What’s So Amazing about Grace? [revised and expanded after 25 years.] I have that kind of “prove it to me” attitude as I circle around these questions, not just accepting what everybody would automatically say because I learned not to trust that, but to really pursue in a careful, systematic way and only talk about things that I feel confident in and other things I just don’t deal with.

Something that stood out for me in What’s So Amazing About Grace? was how you said God shows a marked preference throughout the Bible for the real people, not the good people. I found that so comforting.

When you think about it, who are the giants of the Bible, the real giants? Well, you have to say Moses is right up there and David, those two in the Old Testament. Moses was a murderer and had an anger problem that got him in trouble. David was a murderer and adulterer. Well, let’s go to the New Testament: Peter was somewhat like Judas. Judas betrayed Jesus. Peter did the same thing, saying “I never knew him …” three different times. And then the Apostle Paul, well, he was converted after spending several years as a terrorist, sniffing out Christians, persecuting and helping murder them.

The Yancey brothers, 1960.

And those are the best of the lot – Moses, David, Peter and Paul. So no one can say, as you may be tempted to do, “Oh, God can’t possibly use me. I’m beyond the pale. God can’t forgive that.” I think God deliberately chose those people, the giants of the faith, as it were, so that we can’t say, “I’m beyond the reach of grace.” No, no, look at these. They’re the best.

I noticed that in What’s So Amazing about Grace, you tell your family story but under pseudonyms, as if it were happening to someone else. And then, in your memoir, you come out of the closet, so to speak.

That’s right. Yes. For years, I was frightened to write my story because the people who were the main characters were still living.

I did finally publish it. My mother had turned 98, and I decided, “Now’s the time.” I didn’t know how much longer I would be able to write. So I worked on it for about three years, and it was published about six months before she died. She died just after turning 99. And in that last year, after I had turned in the manuscript, which tells the story about my brother and mother not speaking for more than 50 years, they actually had their first contact, and I got them both on the telephone three or four times.

They didn’t go especially well, but at least they made contact. And then my brother, unprompted, on his own volition, wrote her a card that had three words in it: “I forgive you.” I had been afraid to use their names to write my story, thinking it would just destroy them. Actually, almost the opposite happened because of the coming to terms with it. We tend to push those things down and not deal with them. Sometimes, when you lance that boil, even though it looks messy, it’s the only way for healing to come.

“Grace doesn’t give us what we deserve. In fact, it gives us the opposite.”

You’ve written What’s So Amazing About Grace, but you also discussed what’s so hard about grace. Can you explain that to me?

Well, grace is just plain unfair … The hard thing about grace is we’re so used to, in a capitalist competitive economy especially, earning our way, being paid by how much we’re worth, how much we deserve, and the world runs that way. But God does not. Grace doesn’t give us what we deserve. In fact, it gives us the opposite. We deserve God’s wrath; we get God’s love. We deserve God’s punishment; we get God’s forgiveness. The Pharisees were ticked off at Jesus going around talking about these sinners and hanging around party people and tax collectors and people like that. They were mad at Jesus because he wasn’t going by the rules. Now, you’re right – God doesn’t go by the rules. God breaks the rules again and again.

That’s what grace is all about. So it’s hard. It’s kind of unhuman. I remember having a conversation one time with the singer Bono of U2. I’d just read a book he wrote based on interviews he had with a French agnostic journalist, and Bono kept trying to explain why he’s a Christian to this journalist who couldn’t figure out why would anyone want to be a Christian.

And finally, Bono says, “Well, at the end of it, it boils down to either the world runs by karma or by grace. And I’m going to cast my lot with grace.” Most religions and a lot of Christians run by karma – “I’m going to get what I deserve.” I don’t run that way. And I don’t think Jesus did either. He said, “There’s another way. It’s an easier way. Seems hard, but it’s actually easier.” You’ve just got to overcome your pride and accept that God’s love is a free gift. It’s not something you have to earn. It’s already there. You just have to act on it.

Philip Yancey

And yet we all battle daily with pride and judgmentalism and a feeling that we somehow need to earn God’s approval. How can we just accept God’s love and stop trying to earn it?

One way I know is to find people who don’t have that option of looking upon their good deeds. I’ve learned a lot from the recovery movement. I’ve gone with friends to Alcoholics Anonymous and groups like that, and they start every meeting by saying, “Hi, I’m Bob; I’m an alcoholic.” “Hi, I’m Joy, and I’m a drug addict.” They start with their weakness. They start with the worst part about them, and that’s why they’re at the meeting and acknowledging, “I can’t make it on my own. I live by the grace of God.”

“Grace is free gift … but to receive a gift, you have to hold your hands out.”

I went one time to Folsom Prison (of The Folsom Prison Blues song by Johnny Cash). It’s a maximum security prison in California, and there was a group studying my book on grace. They said, “We’d like to teach you what we know about grace.” They told me that you couldn’t get by for one day without grace in that place. And I realised that’s really where we learn grace – hanging around people who are in recovery, who aren’t making it and know they’re not making it. If you hang around people with leprosy, or people who don’t have a place to live, homeless people, or some people who have addiction disorders, you’ll quickly find the veneers that we live by don’t work, and they admit it. The only way for cure is to cry out for help.

Henri Nouwen used to say that grace is free gift. [There is] nothing you can do to earn it by definition. It’s free, but to receive a gift, you have to hold your hands out. And it’s religious people like the Pharisees who have their hands closed tight in a fist, thinking, “Well, I’m better than that guy over there. Look, he’s a tax collector. He’s a sinner.” When you do that, the gift falls to the ground and you don’t receive it. So it’s the people at the lower end of success in the world, who teach me to keep my hands out so I don’t end up like that Pharisee over there.

Philip Yancey has a new book out Undone, a modern rendering of the work of John Donne, one of the great minds and great poets of English literature. He is also finishing a book about the religious and social background to the Russia-Ukraine war.

Pray

Some prayer points to help

Having spent most of his life writing about pain and suffering, Philip Yancey seeks prayer for wisdom in choosing how to spend the rest of his life. He feels he may have two or three books left in him. “What should they be? What has equipped me in these last days to speak most urgently? I don’t know the answer to that question right now.”