The novel and appealing arguments of prominent Turkish Muslim thinker Mustafa Akyol take centre stage in a new book, Jesus Through Muslim Eyes, by a specialist in Muslim thought, Richard Shumack.

A Centre for Public Christianity (CPX) fellow, Shumack has written the book in answer to Akyol’s provocative 2017 book, The Islamic Jesus.

“With Christians, we (Muslims) agree that Jesus was born of a virgin, that he was the Messiah, and that he is the Word of God. Surely, we do not worship Jesus, like Christians do. Yet still, we can follow him. In fact, given our grim malaise and his shining wisdom, we need to follow him,” wrote Akyol in The Islamic Jesus.

In Jesus through Muslim Eyes, Shumack gives a sensitive and nuanced commentary on how Muslims like Akyol can meaningfully claim Jesus as the Messiah and the Word of God. And how Christians can respond to such claims. Eternity investigates:

What is so provocative about Mustafa Akyol’s ideas?

Let me just give you a bit of a history of most Muslim takes on Jesus, which is part one of my book. I walk through the landscape of how Muslims have thought about Jesus through the years.

Arabia had thriving Christian communities and Jewish communities, so Jesus was not an unknown figure. Muhammad clearly knew about Jesus. There was no Bible in Arabic, so very few of the early Muslims would have read a Bible.

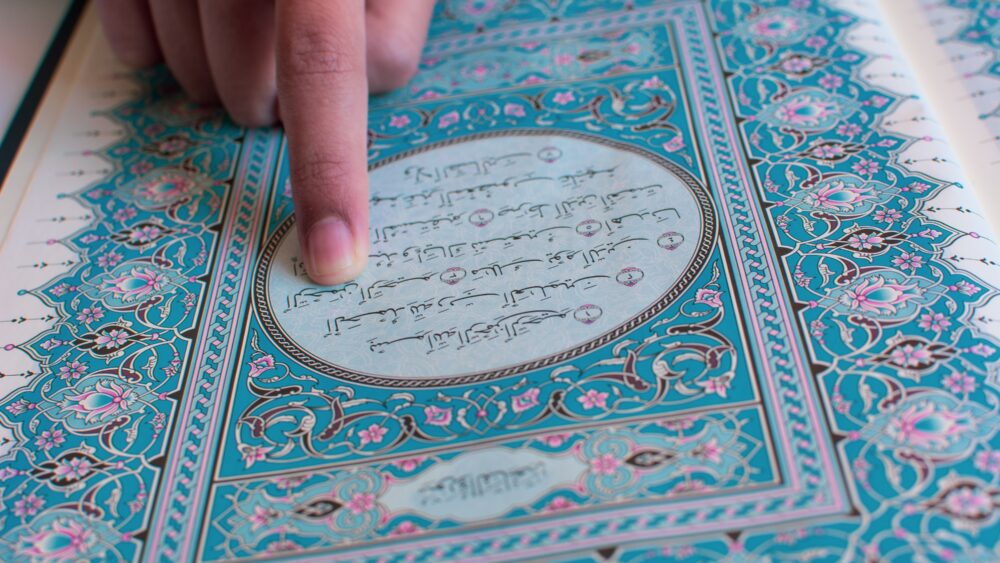

They’d heard lots of stories, but it was all oral. When the Koran came down, it said “we’re happy to have Jesus as Messiah and born of a Virgin and doing miracles, but we’re not happy with him dying on a cross. We’re certainly not happy with him being God.” So there was this sense of “we like Jesus, but we need to correct you on a few elements.”

How did they reconcile him being the Messiah and not the Son of God?

That comes down to what you think a Messiah is and it’s very unclear. Muhammad, and the heroes of the Koran to the Koran’s audience, they’ve heard about this guy Jesus, who was Al-masih or the Messiah, but they didn’t really know much theology, so they didn’t understand the Old Testament backstory of who the Messiah was supposed to be.

The idea of aligning Messiah with the King when Jesus turns out proclaiming the kingdom of God, a Jew will think that’s messianic language, but clearly the early Muslims did not understand it like that. So Messiah was an honorary title, but it didn’t carry a lot of meaning. In fact, even today, if you ask a Muslim what a Messiah is, they won’t really have an answer. It’s just like Jesus’ name.

Then a separate parallel tradition grew up in Islam, Sufism, which was a sort of mystical tradition within Islam. They view Jesus as a mystic. And they thought Jesus was great – he was unmarried, and he was on the road – “like foxes have dens, but the Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head.” So for the Sufis, he was an amazing model of an ascetic who gave his life fully to God, stayed away from worldly affections.

Interestingly, the Sufis over hundreds of years started to draw quite heavily from the gospels and Christian tradition to promote this mystical model. And again, he was not the Son of God for them, but he was a model and a good mystic.

So we had these twin threads, but they didn’t really interact much. So Mustafa Akyol’s innovation, if you like, his creativity, was to try and draw the threads together, trying to create a Jesus that was both a good devotional model for a Muslim, like a good model of what it is to be holy person, but at the same time trying to make him feel theologically aligned with Islam better.

And he drew on a lot of Western sceptical Jesus history scholarship to say, well, actually, the true history of Jesus was more like the Jewish Christian sects, not mainstream Christianity. Mainstream Christianity got Jesus wrong

So the way Christianity developed was, supposedly, a heresy of the original?

Yeah, right. So there was an original Jewish Christianity centred around James in Jerusalem, and then there was an aberrant Christianity that centred around Paul later on and developed out of Rome.

That’s sort of the narrative in a nutshell. Jewish Christianity died off; heretical Christianity become dominant.

So that’s very provocative. How do you counter that?

Well, the way my book wrestles with that is to start by outlining the Muslim Jesus and try and take him on his own on terms and try to outline that story, particularly the one that Akyol tells.

I evaluate that against the history and against the theology or things like Messianic expectations, and then finally devotionally too, see whether that works even within Islam – was it possible for Islam to adopt Jesus as a devotional figure?

Was it possible for Islam to adopt Jesus as a devotional figure?

So I look back at the historical documents around early Christianity … and sects like, for example, the Ebionites, which is a very early sect, whether they were true Christianity. We know almost nothing about the Ebionites. We have a couple of very short texts in the early Christian writings. We don’t even know really what they believed, we don’t know who they were. So the idea that somehow they were true Christianity just doesn’t stack up historically. And that’s just one example. I look at the various historical claims. And say, “well, at best it’s controversial; at worst there’s just no real evidence for it.”

Are Akyol’s views widely held in the Muslim world?

Well, he’s new. So this is a new and innovative take on it. So it’s hard to know how much people have bought in. It’s certainly true that the traditional position I was talking about before is very widely held among Sunni Muslims.

It’s also true that that idea of Jesus being a good devotional model is at least popularly held. There’s not a lot of rigorous thought that goes into that.

I remember years and years ago, I ran into a Muslim friend of mine, just this young guy outside a gym, and he was wearing a T-shirt. And the T-shirt says, “I love Jesus because I’m a Muslim,” and then on the back it said “and he was too.” And so, there’s this strong sense of Muslims saying, “We love Jesus and he’s one of us and he’s a good model of what it is to be a holy person.”

But again, they also don’t really know much about him. So I asked my friend, “What do you love about him?” And he said, “I don’t know much about him at all. It was a free T-shirt at the mosque.”

Do you think this new and innovative take on Jesus is a stepping stone for Muslims towards Christian faith? Or is it an obstacle because it blurs the truth?

I tackle that question in the devotion section of my book.

I think it’s helpful in the sense that I love anything that gets us talking about Jesus and who the true Jesus is and how we can find that out – and particularly when it doesn’t stay in the academics but asks real questions about what devotion to Jesus looks like.

Akyol says some quite controversial things in an Islamic sense. He says things like, “Well, actually Jesus is a better model for Muslims to live in the West or to live in the modern world than Mohammed is,” and he’s got a few reasons why that is, and it seems to me that it’s very controversial in Islam.

In Islam, Mohamed’s the pre-eminent, he’s the ultimate prophet. He’s the one that provides the best model of what it is to be a human. But the idea that Jesus somehow is better or more appropriate for now – I’m not sure if Muslims could accept that – but the broader theology, yeah, I think they’d probably could, particularly the historical stuff.

So that the idea that what’s now Orthodox Christianity is a corruption – Muslims through the years have had various different theories about how that might have taken place. So who corrupted? When did it happen? When was the Bible changed? How was original Christianity suppressed? Lots of different takes – there’s not a consensus on that.

And so what I run through in the second part of the book is looking at all the different supposed culprits for that which Muslims have identified.

Is the book primarily aimed at Christians?

No. I’d love Muslims to read it primarily, but I’m also very aware that most Muslim discussions or thinking around Jesus usually is instigated by interactions with Christians one way or another. Really, what I’d like this book to be is a discussion starter, something for Muslims who want to talk about Jesus – here’s some material you can toss around together. I’m expecting that that’s the way it will happen.

I’d love someone just to pick it up and read it.

Then it could leave the path open for the Holy spirit to do his work.

Yes, and at the end of the book, the book is not merely descriptive. I land quite heavily on, well, actually I think the Christian Jesus is the real Jesus. I’m advocating for him and trying to explain what a true devotion to Jesus of the Bible looks like. I’d like to think a Muslim can be led part of the way there through reading the book to the gospel.

Which is what your role with CPX involves!

Yes. My favourite section is the section on the cross because one of the real distinctives between the two Jesuses, the Muslim and the Christian Jesus, is that the Christian Jesus is absolutely aimed at the cross. His life is cruciform and everything comes together, all the threads around who the Messiah is and why Jesus came and why he needs to be the Son of God or all of the sort of objections that Muslims have, they all actually come together at the cross.

His life is cruciform and everything … comes together at the cross.

That’s literally the crux. The Muslim Jesus stepped around the cross – he was about to be there and then he stepped around it and avoided it. And for me, that’s the real critical point, the critical difference: the Muslims think he just walked around the cross and went straight to heaven. And if you can get that, then you can get to the heart of Christianity.

Pray

Some prayer points to help

Pray for good engagement with our Muslim neighbours. Pray that the true identity of Jesus may be revealed.