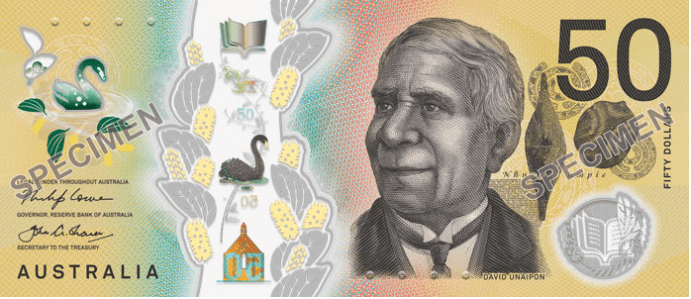

A new $50 banknote will enter circulation next week, retaining the face of David Unaipon, and an image of the Raukkan Church, which sits at the heart of the small Aboriginal community of Raukkan where Unaipon was born, on the banks of South Australia’s Lake Alexandrina, 80km south-east of Adelaide.

Here is the story of David Unaipon, as told by Bible Society Australia’s historian, John Harris:

The first adult Christian at the Point MacLeay Mission, near the mouth of the Murray River in South Australia, was James Ngunaitponi, a Ngarrindjeri man whose name was Anglicised to ‘Unaipon’ by white people who could not pronounce it.

The mission, technically non-denominational, was conservatively evangelical and ruled by the stern George Taplin. James Unaipon, born about 1830, came to Christ in 1862 through the teaching of a far gentler itinerant missionary, James Reid of the Free Church of Scotland, whose name James took at baptism. He chose to accompany Reid, acting as a translator and taking his own first steps towards evangelism.

He dedicated his final years to evangelism, travelling widely on foot to Adelaide and country towns of South Australia.

Reid was tragically drowned in 1863. In 1864 James settled at the Point Macleay Mission. Taplin was delighted and, to give him his due, he encouraged James to evangelise his own people. James was the first of those Aboriginal evangelists later known in South Australia as the ‘Taplin men’. James learned of other Christian Aboriginal people at other missions and linked up with James Wanganeen of the Church of England Poonindie Mission. Taking with them a young Point Macleay man, William Kropinyeri, they undertook missionary journeys along the Coorong and to other places where the Gospel had not yet been preached.

Better known to Australians was James’ son, David Unaipon, the face on our $50 bill. An inveterate reader as a child, he grew up to be a remarkably intelligent and learned man with wide academic interests. Entirely self educated, he was a natural scientist, who patented many scientific and technical inventions. He read the classics and could quote huge slabs of Bunyan and Milton. Newspapers dubbed him ‘the black genius’ and ‘Australia’s Leonardo’.

He had an immense knowledge of the Bible, the King James Bible of course, and knew huge sections of it off by heart. He was obsessed with correct English, the English of the classics which he so ardently read and of course the language of the King James Bible.

For his public speaking he developed a pedantic style of oratory which owed more to the classics than it did to current English usage, particularly the broad Australian idiom of rural South Australia. He became quite famous, regularly sought as a speaker in the southern states. He was a political activist in his eccentric own way, a kind of unofficial spokesperson for what he termed ‘Aboriginal advancement’. ‘Look at me’, he used to say, ‘and you will see what the Bible can do’. David Unaipon defied the stereotype of the lazy, ineducable Aborigine and thus made many people uncomfortable.

But with all his talents and eccentric interests, what he loved doing best was preaching the Gospel. A Christian all his life, David Unaipon was a vigorous, outgoing preacher who modelled himself on the forceful, Bible-based style of the missionary preachers who had influenced him. With Aboriginal people he preached in the Ngarrindjeri language but elsewhere he preached in his idiosyncratic brand of English, His sermons were full of Biblical allusions, from the King James Bible of course, and it was said that he even sounded like the King James Bible.

For all his learning, David Unaipon never lost touch with his Aboriginal roots. He collected and recorded Aboriginal stories. He researched Greek and Egyptian mythology at the South Australian Museum, and came to understand Aboriginal stories as having a similar weight and purpose. He published three books of Aboriginal legends.

In a Christian sense, David’s greatest contribution was in his old age. By the time he was about 80, younger Aboriginal people were taking over the role of campaigning for Aboriginal rights and he was less courted by the influential and the newspapers. He dedicated his final years to evangelism, travelling widely on foot to Adelaide and country towns of South Australia, regularly refused accommodation because of his race and often being detained by the police. David died aged 94, convinced he was about to discover the secret of perpetual motion.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?