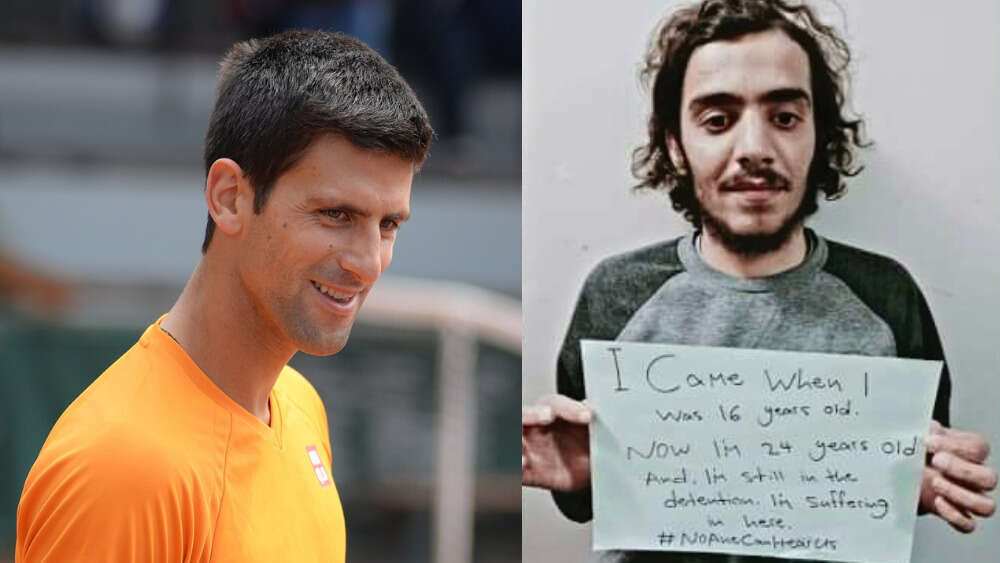

Melbourne’s Park Hotel has been in the news for all the wrong reasons this week. It’s where tennis star Novak Djokovic was temporarily detained when his visa was declined on entry to Australia. It’s also where 32 refugees and asylum-seekers are being detained — and have been detained, in some cases, for nine years.

One of them is Mehdi Ali, who arrived in Australia from his native Iran aged 15 and has been formally recognised as a refugee by the federal government, and yet is still being held in immigration detention. Last week he tweeted:

“It’s so sad that so many journalists contacted me yesterday to ask me about Djokovic. I’ve been in a cage for 9 years, I turn 24 today, and all you want to talk to me about is that. Pretending to care by asking me how I am and then straight away asking questions about Djokovic.’

Mehdi asks a searching question of us: Why do we care? Why have we vented so much rage and spilled so much proverbial ink on a tennis star detained for mere days — while for refugees detained for many years we can do little more than shrug our shoulders, if we even notice them at all?

At least part of the reason is anxiety. It’s been widely reported that the pandemic we’re living through has driven an epidemic of anxiety. We all live with anxiety now, in a new way, with the ever-present threat of another outbreak or forced isolation.

One of the things that anxiety does is to narrow our concerns. Because we’re anxious about the pandemic, all our cares are filtered through that lens. We might even find scapegoats on whom to project our fears and anxieties. Maybe none of the last week’s outrage has really been about Djokovic at all.

Maybe none of the last week’s outrage has really been about Djokovic at all.

But there’s an alternative. Our scapegoating has inadvertently brought to light a long-forgotten injustice. We’re paying more attention to Mehdi and his 31 fellow detainees than we have in a long time.

The dark and light sides to this story — the anxiety-fuelled rage on the one hand, and the renewed concern for justice on the other — have been on display throughout the pandemic.

On the one hand, we’ve become attuned to those around us who disagree about how the pandemic is best managed, judging their laxity or obsessiveness regarding whatever the current restrictions are. We’ve heard people demonise particular suburbs, and even entire suburban regions, quick to suggest that “those people” are the ones whose behaviour has got us into this mess.

On the other hand, there have been stories of genuinely rediscovering community, and noticing disparities between how different suburbs and classes have been affected by the pandemic and treated by government interventions.

The challenges, pressures, and injustices faced by people with disabilities, those who struggle with mental health and Aboriginal communities have been brought to the forefront of our collective consciousness, along with a new sense of how dependent we are on the work of the chronically underpaid: truck drivers, nurses, supermarket staff.

And we’ve looked on with rightly-raised eyebrows as the famous have consistently been granted “exemptions” from quarantine.

The pandemic, then, can teach us the wisdom of God’s proverb: ‘The rich and the poor have this in common: the Lord is the maker of them all’ (Proverbs 22.2). In other words, we’re not that different from one another. And, therefore, we’re all in this together. The pandemic can be — should be — a great leveller. And in God’s kindness, such a leveller could even realign our hearts toward his justice and grace.

But in order to do that we need to deal with our anxiety in a different way. The Apostle Peter counsels us: ‘Cast all your anxiety on him, because he cares for you’ (1 Peter 5.7). God himself invites us through his word to project our anxieties and fears onto him, and nowhere else. He’s provided us a scapegoat — one who has willingly shared our sicknesses and carried our pains (Isaiah 53.4). Our spiritual challenge is to look up from our own anxieties and instead look at him: at Jesus, who has carried it all for us, and who will come again to make all things new (Revelation 21.5).

If we can do that, then maybe, just maybe, God can renew our sight, so that we can see things rightly: to see injustice; to walk in love, seeking the common good. If we can cast all our anxieties on him, then maybe, just maybe, we can care a little less about Djokovic, and a little more about Mehdi.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?