Pilot program aims to prevent child sex abuse with helpline for potential perpetrators

Please be advised that this article discusses child sexual abuse and may be upsetting for some readers.

Jesuit Social Services (JSS) will pilot a new program that aims to prevent child abuse by providing support to individuals regarding their own or someone else’s sexual thoughts and/or behaviours towards children.

The program, called Stop It Now!, has operated successfully in North America, the United Kingdom and Ireland (since 2002) and the Netherlands (2012). Its key feature is an anonymous phone helpline for people who are worried about their own sexual thoughts and behaviours in relation to children, as well as professionals and family members who are concerned about the behaviour of others. The service also includes a website with advice, self-help materials and guidance to raise awareness around child abuse.

Stop it Now! is dedicated to reducing or eliminating the sexual abuse and exploitation of children and seeks to achieve this by engaging with adults who may go on to harm children. While the service can be accessed both anonymously and confidentially, all mandatory reporting guidelines will be complied with.

Stop It Now! was selected as the best model for the pilot program following a detailed study undertaken by JSS in collaboration with the University of Melbourne. The study, which examined models for early intervention, found that Stop It Now! has proved successful in other countries and offered “a significant opportunity to counter child sexual exploitation in Australia”.

A major bank is initially sponsoring the pilot. If successful, JSS hopes the program will receive government funding to continue. The University of Melbourne will remain involved in the setup and evaluation.

JSS’s ‘The Men’s Project’ Executive Director Matt Tyler told ABC Radio Melbourne, “in Australia, at the moment we’re missing a really critical prevention window.”

“On average there’s a 10-year window between someone first becoming aware that they’ve got these concerning thoughts and behaviours, and then that person coming to the attention of police,” Tyler said.

The one-year program is expected to receive around 5000 calls.

Stop It Now! ‘s history

According to JSS’s scoping paper:

“Stop It Now! was established in the United States 26 years ago, in 1992, by Fran Henry, a survivor of childhood sexual abuse who recognised that prevailing approaches to keeping children safe were inadequate. She argued that the sexual abuse of children should be treated as a preventable public health problem, and that adults (parents, survivors, family members, law enforcement, professionals and even potential perpetrators) needed to take more responsibility for preventing sexual abuse of children.”

The program has already been used in Australia.

“In 2006, Stop It Now! was launched in Bundaberg, Australia, as an initiative of Stop It Now! UK in collaboration with local social services organisation Phoenix House. The then director of Phoenix House, Kathryn Prentice, had a particular interest in the program, having studied it as part of a Churchill Fellowship.

“Phoenix House successfully ran Stop It Now! for around 10 years in the Bundaberg region, with a phone-in service and off-site counselling. The program was run on a very tight budget, due to a lack of philanthropic or government funding, but those involved were confident that the initiative had an impact in reducing offending. The Phoenix House experience also showed that men with concerning thoughts would approach an organisation for assistance and that there was a clear market for both the helpline and counselling services for this group. The Phoenix House program ceased operating in recent years.”

The need for ‘Stop It Now!’ was identified by the Royal Commission research

JSS’ pilot program of Stop It Now! is a direct response to a problem identified in the work of the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse – Australia has a gap in services to support potential offenders and prevent them from becoming abusers.

In 2017, Vicky Saunders and Professor Morag McArthur published a research paper conducted for the Royal Commission on Help-seeking needs and gaps for preventing child sexual abuse. The paper included a service-mapping exercise (i.e. mapping what services were available) and interviews with 23 existing service providers responding to the target groups’ needs.

Their study identified eight key target groups relevant to preventing child sexual abuse in institutional contexts and child sexual abuse more broadly. They are: adults with problematic sexual thoughts toward children; adult child sex offenders; family members of adult child sexual offenders; professionals working with children (including teachers, school counsellors and sports coaches); parents and family members; community members; young people with problematic sexual thoughts and/or behaviours; and children with sexually harmful behaviours.

“Each of the target groups described a range of challenges to accessing information and support about preventing child sexual abuse. Such challenges included problems with recognising issues, accessing support services, having a knowledge and awareness of services, and the availability of those services. For those individuals (adults and young people) with problematic sexual thoughts, there was an additional layer of complexity: fear of being reported, fear of persecution, stigma, shame and guilt. Such feelings often prevented these individuals from seeking or accessing services,” the report stated.

The study described the range of internal and external barriers that prevent individuals from accessing support and assistance for problematic sexual thoughts about children. For example, it states, “denial is high among men accused or convicted of child sexual abuse offences”. This denial occurs for several reasons, including “a lack of insight, the fear of the familial, social and legal consequences, and the desire to maintain a positive self-image.”

A lack of preventative services

Added to these significant obstacles is the lack of available preventative services:

“Participating service providers highlighted that there are currently no primary prevention interventions available in Australia that focus on individuals with problematic sexualised thoughts about children. Furthermore, secondary interventions such as counselling and support services – which aim to change the trajectory for those at risk of perpetrating child sexual abuse – are also severely limited. While a range of support programs exist for child sexual abuse offenders within the criminal justice system, this study found only one community organisation in Australia that actively offers support to individuals to address their sexualised thoughts before they act on them. Helpline service providers stated that they have limited places to refer these individuals.”

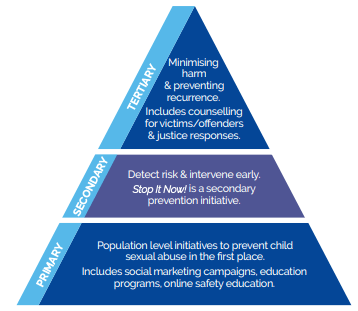

Stop It Now! is an example of a secondary prevention

program. However, it may serve as a tertiary prevention program in certain instances, such as when callers have already abused a child. Source: Stop It Now: A Scoping Study on Implementation in Australia / Jesuit Social Services Stop It Now: A Scoping Study on Implementation in Australia

In interviews, service providers generally understood the concept of “preventing” child sex abuse as involving the provision of victim/survivors of child sexual abuse with responses like helpline counselling and support services, face-to-face counselling, and referrals that could prevent any further trauma or negative impacts for them.

Service providers who worked with offenders similarly understood prevention, with a critical focus on deterring and preventing further offending.

“The people we work with have already crossed the line and committed an offence. Our focus is targeting what has put the community at risk and putting resources around that,” one Service Provider (PS2) told researchers.

Focus groups with community members, professionals and parents “also highlighted that the definition of ‘prevention of child sexual abuse’ was understood as more about learning to ‘pick up the signs’ of when a child may have been sexually abused or when an adult had offended, to prevent further offending or trauma.”

“Some community members and parents spoke more about their scepticism that child sexual abuse could be prevented. One parent commented: ‘I don’t know if you can prevent it – I don’t think you can prevent it but you might be able to minimise duration and effect’.”

So what have people who have problematic sexual thoughts about children done until now if they wanted to seek help? Those seeking help have had to call a more general helpline about preventing child sexual abuse and hope they could provide a referral for further care.

“We have over 4,000 organisations to refer to [for other callers], but there is definitely a lack of specialist support services for these callers – they are a bit thin on the ground,” one Service Provider (HL4) is reported as saying.

Despite the lack of services, service providers told researchers that men with problematic sexual thoughts towards children do access telephone helplines as a means of support.

One helpline service provider (HL8) stated that “if a telephone helpline were established specifically to respond to the needs of this group, ‘it would be flooded'”.

“The bottom line is we need more programs to deal with perpetrators… There are hardly any programs anywhere that deal with perpetrators, they are virtually non-existent… you might have a couple in each state… the need is far greater than that,” they said.

Additional barriers to potential perpetrators getting help

Another barrier for those who seek help is cost.

“All helplines that reported receiving calls from men highlighted the difficulties they had with referring them on to other services for longer-term counselling and support. As noted earlier, there are specialist private psychologists available; however, service providers indicated that the costs associated and the lack of services for those living in regional and remote areas are problematic. Some service providers also said that while a Medicare rebate may be available for some individuals to assist with this cost, the duration of that rebate scheme does not support the long-term work required for this group of individuals.”

In fact, researchers found that it wasn’t until someone with problematic sexual thoughts about children began to act on those thoughts that they could access specialised help.

A further issue is that of confidentiality. Service providers said that “individuals accessing services need a protected and judgement-free environment, and that the offer of anonymity is a key enabler to men seeking support.” But referring someone anonymously to specialised help is not easy.

“The availability of a service that is safe and confidential and can guarantee someone’s security if they don’t disclose any offending… and if there was a service that could provide such a thing I think that would be a really good thing to do,” said a Service Provider (PS8).

While all service providers agreed that there must be a limit to confidentiality and that if a child was in danger, the police must be informed, they also reported that men who called for help often hung up if they learned they were speaking to a mandatory reporter.

If you would like further information about Stop It Now!, go to Jesuit Social Services’ ‘The Men’s Project’

If you have found the subject matter of this article upsetting and need further help, here are some options for Australian readers.

Police: Phone 000 if you’re worried about your safety or a child’s safety at any time.

National Sexual Assault, Domestic Family Violence Counselling Service: Phone 1800RESPECT or 1800 737 732 – 24 hours, seven days a week.

Lifeline: Phone 131 114 – 24 hours, seven days a week.

Kids Helpline: Phone 1800 551 800 – 24 hours, seven days a week.

Bravehearts: Phone 1800 272 831 – 8.30 am-4.30 pm, Monday to Friday AEST.

If you are outside Australia, please seek help in your local area.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?