What is your reaction to the words, “biblical critical theory”?

Suspicion? Excitement? Indifference?

We instinctively form expectations, especially when it comes to an unconventionally titled book that’s generating lots of buzz. But so often, reality dispels our expectations. Hence the saying: Don’t judge a book by its cover.

Whatever your first impression of Christopher Watkin‘s Biblical Critical Theory, you’ll find the reality compelling, insightful, visionary and, the author hopes, a bit strange.

Christopher Watkin’s Biblical Critical Theory won the Sparklit Australian Christian Book of the Year award.

Surely ‘biblical’ and ‘critical theory’ don’t mix?

Watkin acknowledges that the term ‘biblical critical theory” has “caused quite a few people to scratch their heads, or even to raise their eyebrows”. He quickly clarifies that he does not mean “critical theory” in the sense that has recently become all the rage. Watkin is not advocating for a biblical version of “critical race theory”, but using the term in the broader (more original) sense of a cultural theory that does three fundamental things.

“The Bible is doing the same things as these critical theories – not coming to the same conclusions, but making the same moves.” – Christopher Watkin

First, critical theories make things viable. You might think, says Watkin, that a revolution of the working class is impossible. But if you read the critical theory of Karl Marx, you might start to see it as a possibility.

In the same way, while the idea of taking the promises of the Christian God seriously is often unimaginable for the average person on the street, God’s trustworthiness throughout the biblical story enables us to see how dependence on him might be possible and, ultimately, preferable.

Second, critical theories make things visible. Before the 20th century, Watkin notes, people either didn’t notice or chose to ignore how women were discriminated against. But feminist theory intends to help you see the treatment and situation of women in new ways.

Similarly, while we’ve all seen countless sunsets, until we’ve read Psalm 19, it may never cross our minds that each sunset is a witness to us of God’s glory, for which he should be praised.

“The heavens declare the glory of God; the skies proclaim the work of his hands.” (Psalm 19:1 NIV) Dave / Unsplash

Third, critical theories make things valuable. “They teach you what to desire,” Watkin continues, “and in a lot of these critical theories, it’s desiring the transgression of norms, [contending that] we should upset traditions and overturn the usual ways of doing things.”

Before becoming a Christian, Watkin would have laughed if you told him he should seek to serve others. But when “the gospel gets to work on you, and you see the Son of Man, who came not to be served, but to serve and to give his life as a ransom for many,” you begin to see that service is desirable and worth striving for.

When we turn to the Bible, Watkin says, we find that “of course it’s the word of God that makes us wise for salvation; it’s a double-edged sword – all of that. It is also doing these three things for us: making things in the world viable and visible and valuable.

“So the Bible is doing the same things as these critical theories,” Watkin concludes. “Not coming to the same conclusions, but making the same moves.”

‘Only the Christian’

Having explained the similarities between a biblical lens and other critical theories, Watkin’s account becomes even more compelling when highlighting the differences.

One of the main distinctions is that the Bible portrays reality in terms of a story – most fundamentally creation, fall, redemption and consummation. It is easy, Watkin warns, to lose sight of how distinctive this portrayal is. For example, the fall, as well as the incarnation, cross and resurrection, represents a cosmic change.

This grants the Christian a uniquely rigorous position from which to say that wrong really is wrong – to measure the world against the standard of the God who is outside and above it. “Only the Christian,” Watkin concludes, “has a position from which she can say that injustice is properly unjust and shouldn’t exist.”

The Bible’s unique power to heal our culture

Bringing out the uniqueness of the biblical world seems to come naturally for Watkin, especially through one of the book’s most memorable motifs: “diagonalisation”.

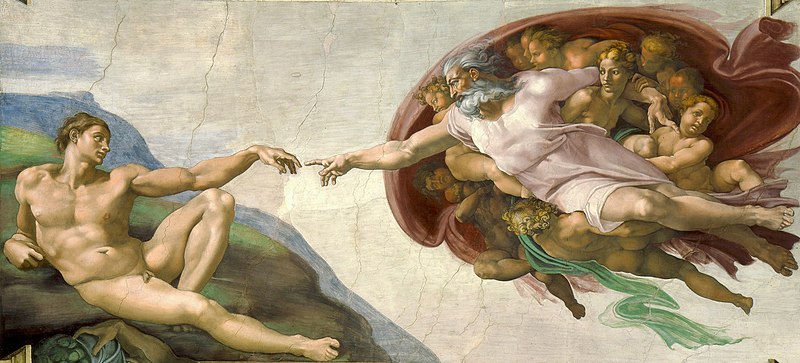

He takes as an example the “beautiful truth” of Genesis 1 that human beings are made “in the image of God”. “In that reality,” he explains, “you’ve got two aspects. Humans have huge dignity, because of all the things in the whole of God’s creation – the Milky Way galaxy, a beautiful sonata, a school of whales or the best art ever made – only humans are in the image of God.

“But there’s also a sense that human beings are being humbled, because if we’re the image of God, that means we’re not God. There’s someone greater and more original than we are, and we only understand ourselves in relation to him.

A photographic reproduction of Michelangelo’s The Creation of Man, illustrated on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel Alonso de Mendoza / Wikimedia

“There’s no sense in Genesis 1 that these are pulling against each other,” he continues, “or that human beings are half dignified and half humbled. There’s harmony.”

Watkin contrasts this beautiful harmony with the extreme dichotomies of modern culture. Modern anthropology tends to see humans, on one hand, as gods, “ripping the idea of dignity out of its biblical context and blowing it up out of all proportion”. It says we should do what only God can, such as define our own reality and decide between good and evil.

But, on the other hand, we are told that humans are basically complicated animals, no different from the rest of creation, or complicated machines destined to be overtaken by the machines we create. Again, Watkin says, this view is grasping for the biblical truth that humans were created from the dust of the ground (“not some sort of cosmic stardust”) on the same day as the animals. But again, that’s not the whole story. We are images of God.

“These things that are opposed to each other in modern cultures are actually dismembered, ripped apart – parts of a beautiful, harmonious, biblical, holy image of God’s idea.”

This tearing apart of biblical truth has profound psychological and social impacts, which we’ve all seen. Since our false cultural dichotomies represent two half-truths, “diagonalisation” is often called a “third-way” approach. But, Watkin objects, “the image of God is the first way. Both of these things that are opposed to each other in modern cultures are actually dismembered, ripped apart – parts of a beautiful, harmonious, biblical, holy image of God’s idea. That’s the original idea, and human sin is always a corruption of God’s original goodness.”

Throughout the book, Watkin traces the biblical storyline, showing how it “diagonalises” and heals countless cultural dichotomies.

Is ultimate reality absolute, like Aristotle’s “prime mover”, or personal, like the gods of ancient mythology? Should we prioritise the sciences or the arts? Should we focus on the community, like traditional societies, or the individual, like modern societies? The answer to all of these questions is “Yes! Both!” because the centre of the universe is one God, absolute and personal, in perfect triune relationship.

And that’s just chapter one.

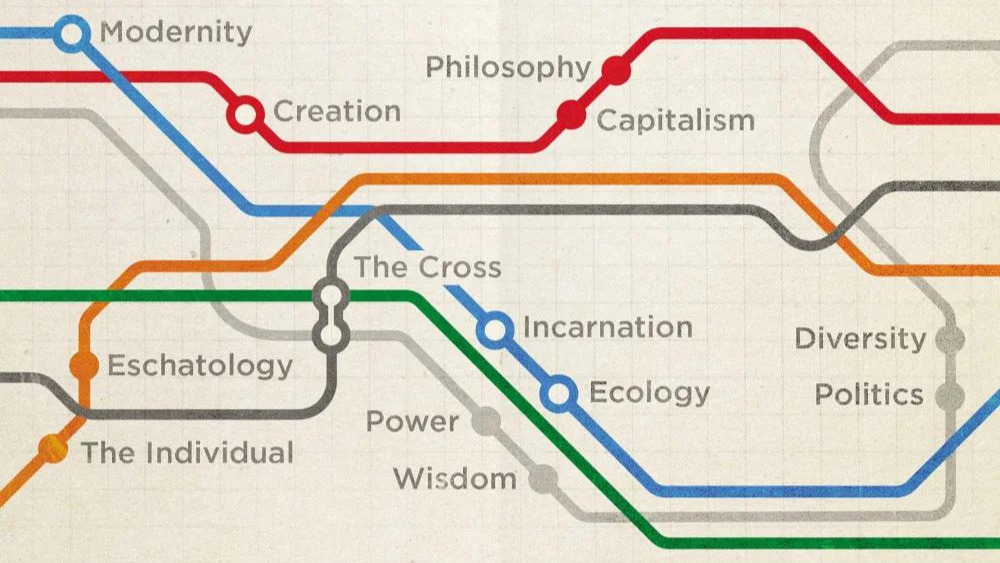

Biblical Critical Theory, by Christopher Watkin

Watkin’s vision

In Biblical Critical Theory and in conversation, Watkin aims to help us see the world through the lens of the Bible. When asked what he would say to the entire Australian church, he responds without hesitating: “If we want to do cultural critique that will honour God and both confront and bless society – because it can’t all be about confronting, and it can’t all be about blessing and comforting; there needs to be both – we will only do that if we press into the riches of God’s word more and more.”

Amen.

Christopher Watkin is a researcher, lecturer and author, lecturing in French studies at Monash University in Melbourne. From 10-12 October, he will deliver the New College Lectures in Sydney (available in person and online). The event is free, but registration is essential, so click to secure your free tickets.