The PM is a good Pentecostal but is he a Good Samaritan?

The pastor and the PM

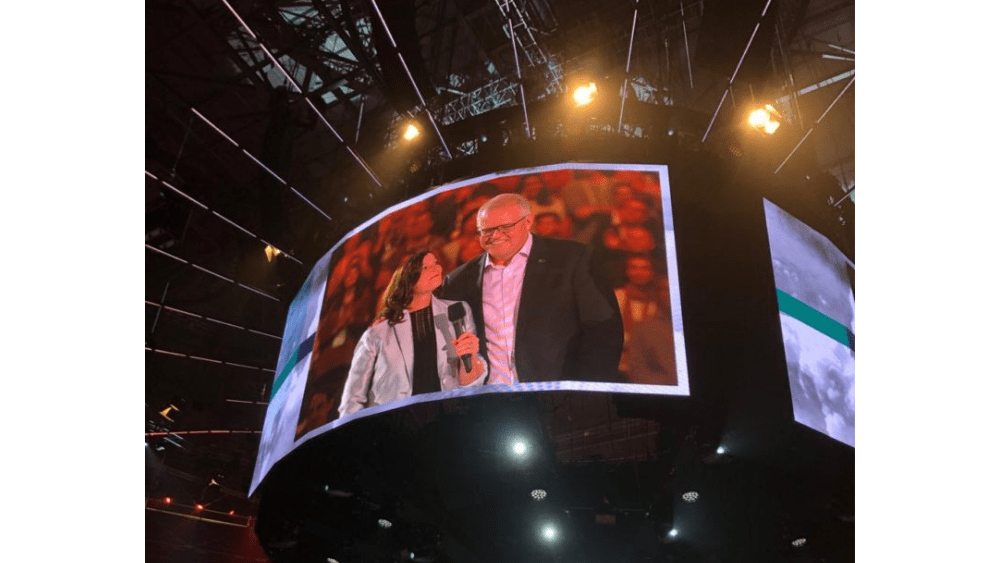

The nation’s most famous Pentecostal, Prime Minister Scott Morrison, stood on the stage of Qudos Bank Arena at Hillsong’s annual conference last Tuesday and urged Australians to treat others with love.

The following morning, just a short distance away, as the PM’s Hillsong visit made headlines, another Pentecostal pastor stood, trembling and shackled by mechanical handcuffs, and made a similar plea.

Luke just wants to be free to devote himself to Jesus

#hometobilo campaigner says God placed Tamil asylum seekers in her life for a reason

With a huge smile, Rosemary serves refugee and migrant women

Why Edris Cheraghi is locked away with no hope of release

But there were no standing ovations for the second Pentecostal. Caught in Australia’s immigration laws, the pastor was returned to immigration detention to continue waiting to find out if a claim for a protection visa would be granted, allowing the pastor to live with friends in the Australian community and have their request for asylum processed.

Human Rights lawyer Alison Battisson, who asks Eternity to refer to her client as “they”, says the contrast between the Pentecostal PM’s appearance at the conference on Tuesday night and her Pentecostal pastor client’s experience on Wednesday morning left her feeling very concerned.

Her client flew to Australia in February on a tourist visa. They had, at the hands of their government, experienced persecution, torture, assault, the seizing of their property, along with death threats against them and their family for political reasons that were connected to religious activities. They always planned to apply for a protection visa in Australia.

Her client’s mistake, Battisson explains, is that her client applied for a protection visa as soon as they arrived, approaching immigration officials at the airport to declare themselves a refugee. As a result, they were handcuffed and taken to immigration detention.

They were provided with photocopies only, which were rejected by the Department of Home Affairs precisely because they were photocopies.

Had her client told immigration officers they had tourism plans and passed through immigration to the baggage claim before disclosing their intention to apply for asylum, their experience would have been entirely different. They would have been issued with an automatic bridging visa and permitted to live in the community while their applications were processed.

Battisson says the initial interview with the Department of Home Affairs was flawed. Her client was told they weren’t allowed to use photos they had to prove their claim, which were being kept in the detention centre’s property vault. Instead, they were provided with photocopies only, which were rejected by the Department of Home Affairs precisely because they were photocopies rather than originals. Her client’s protection visa was subsequently denied.

At this point, Battisson became the client’s legal representative, quickly lodging an appeal for her client’s protection with the Administrative Appeals Tribunal.

This was the appeal that took place the morning after Mr Morrison went to Hillsong. It was lengthy, and was therefore adjourned, upon which Battisson says her client crumbled, began to shake and cry and asked her “Ali, how will I survive?”

She says the pastor, who has been assessed by the Department of Home Affair’s medical expert as showing symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, is not in a position to handle living in immigration detention without a sense of hope or certainty. They aren’t coping well emotionally.

But, having missed the initial opportunity to get a protection visa, her client is now finding the climb out of immigration detention more protracted and difficult because Australia’s compulsory immigration processes are harsh – as is the case for all asylum-seekers who find themselves in the same situation.

One example is the mechanical handcuffs her client wore during the hearing, despite having never been assessed as a security threat of any kind. In fact, her client doesn’t really have any kind of negative assessment at all, with the credibility concern addressed by Battisson getting their original photographs out of the detention centre’s property vault.

Regardless, Battisson explained to Eternity, “Immigration detainees are placed in the same mechanical handcuffs that prisoners wear whenever they are transported to and from appointments of any kind, including medical appointments, during which they are often handcuffed to the bed whilst being treated.”

Battisson is tough and not one to go quietly into the night when there’s something she can do to help her client. Just last year she took a case all the way to the United Nations, which subsequently handed down a scathing report on Australia’s treatment of asylum-seekers, basically amounting to recommendations for a complete overhaul.

She hopes that when Christians become aware of the pastor’s case, they will share the story and call for their protection. Yet, despite her faith in the Christian community’s ability to rally and speak up for her client, Battisson herself is not a Christian. And she doesn’t tip-toe around the PM’s faith, telling Eternity she finds his “hypocrisy overwhelming,” in the face of the toll his immigration laws have taken on her clients.

As Immigration Minister, Mr Morrison oversaw the closing of Australia’s borders to people arriving by boat, declared that no asylum-seeker who arrived by boat would be settled in Australia, whether they were found to be genuine or not. He instigated boat turn-backs, introduced legal changes that made the application process for people seeking asylum more laborious and lengthy, and cut funding to services that assist in the application process.

As Prime Minister, Mr Morrison has cut the overall numbers of refugees Australia accepts, and refused to resettle detainees who have spent six years in offshore detention, rejecting ongoing offers by New Zealand PM Jacinda Ardern to resettle them, and despite numerous UN reports denouncing Australia’s offshore detention. Most recently, he has expressed plans to overturn medevac laws and place medical needs of people in offshore detention back in the hands of Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton.

Suffice to say that Prime Minister Scott Morrison has been no champion for the care of vulnerable asylum-seekers.

“If my client deserves a bridging visa now, they deserved one a month ago, and they deserved one back in February when they arrived,” Alison Battisson

When Battisson began tweeting about the case of her Pentecostal pastor, and threatened to go to the media, within two hours, she was informed the Minister’s Department for Home Affairs had made a recommendation to him that he issue a bridging visa.

This is the most the minister can do now that the matter is before the Administrative Appeals Tribunal and it will most likely help, but Battisson is concerned for other cases that don’t have the option of threatening negative media.

“If my client deserves a bridging visa now, they deserved one a month ago, and they deserved one back in February when they arrived,” she says.

In her view, the entire system is arbitrary and it’s real people whose lives are being ruined by its cruelty.

“And unless you have someone pushing your case, you get left behind,” Battisson says. “That needs to change.”

A previous edit of this article said that the Minister for Home Affairs had made the recommendation, which was incorrect. The Minister’s department has made the recommendation to him, so we have updated this article to correct the inaccuracy.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?