Mike Gore’s life story sounds a bit like a movie script. Abandoned at birth in a field in southern India, he was rescued by a paediatrician, placed in an orphanage then smuggled across state lines so that he could be put up for adoption.

Adopted by a Christian couple in the Sutherland Shire in Sydney, Mike grew up as “a brown kid in a white family”, an experience that exposed him to racism and bullying but developed an inner strength and a deep sense of empathy for the vulnerable.

Now 42, the former CEO of Open Doors Australia is co-inventor of a new app that aims to be the “Uber Eats” of charitable giving. Charitabl. aims to swell the giving pool by making it easy to give to any of 39,000 curated charities. It’s a rags to (potential) riches story of a man whose mantra is “I love God, I love people and I generally love building something out of nothing.”

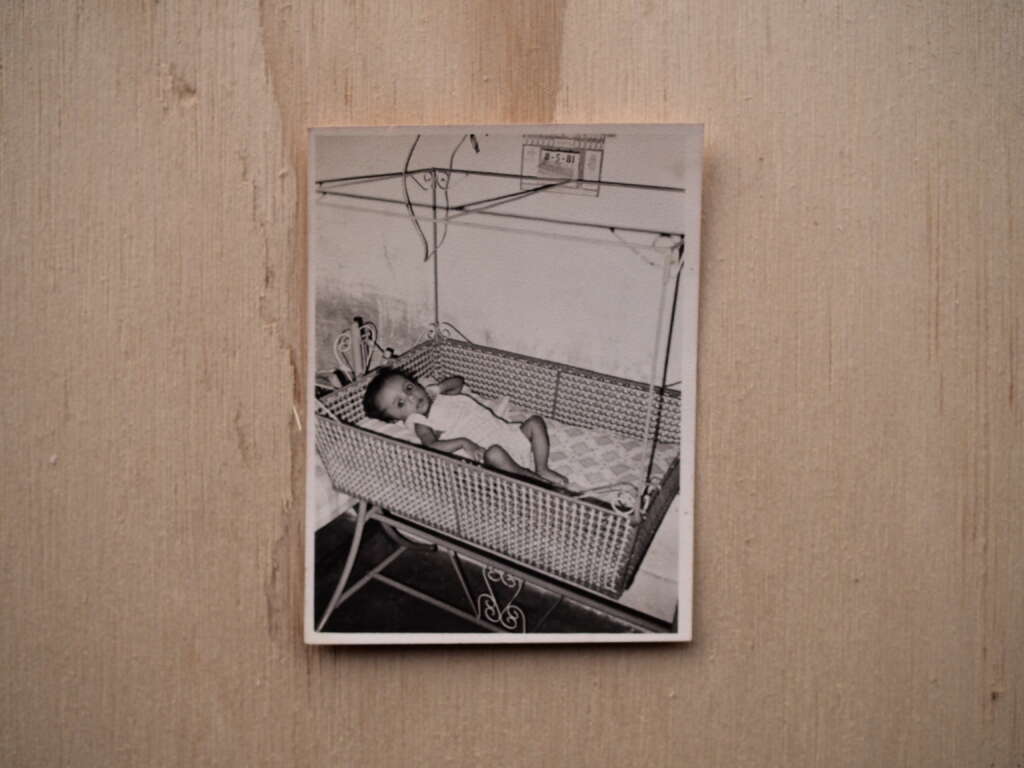

“I was born in 1981 as a Hindu, abandoned at birth, left in a field and found by a paediatrician,” he recounts.

“The paediatrician took me to someone, and they placed me into an orphanage. But because of the caste system in Hinduism in India, they believe what you have done in your previous life determines the circumstances amid which you were born. And so for me to be born out of wedlock and abandoned in a field suggested I’d done something relatively heinous in my previous life, so I wasn’t allowed to be adopted.”

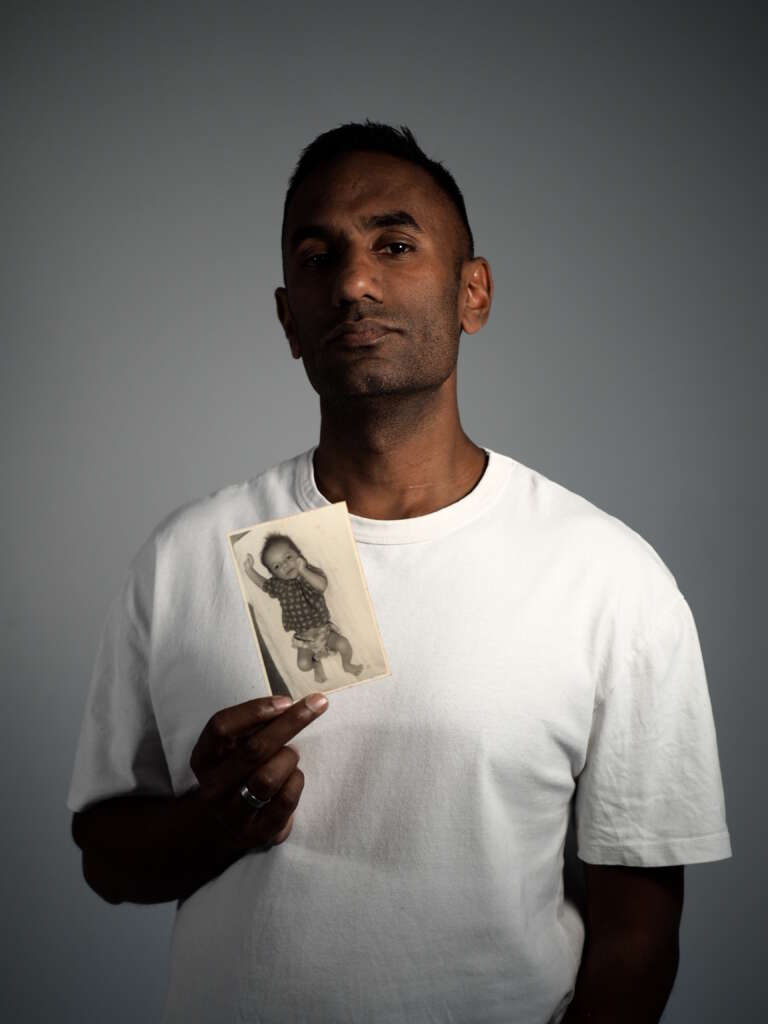

Mike Gore as a baby.

Four years before his birth, a family in Sydney with two biological daughters applied to adopt a child from India. In 1981, having heard nothing conclusive, they decided to spend the money they had saved on a trip to America as a way of closing the chapter on adoption and moving on in life.

“While this was happening, a lady in the orphanage took a liking to me and one night she smuggled me across the state line. She bribed some nuns to say that I was abandoned on their doorstep and they changed my birth certificate, which meant I could be adopted under that state’s law,” Mike recounts.

“When the Australian family got back from their holiday, they got a phone call saying, ‘The adoption’s gone through, and your son will be at the airport at the weekend.’”

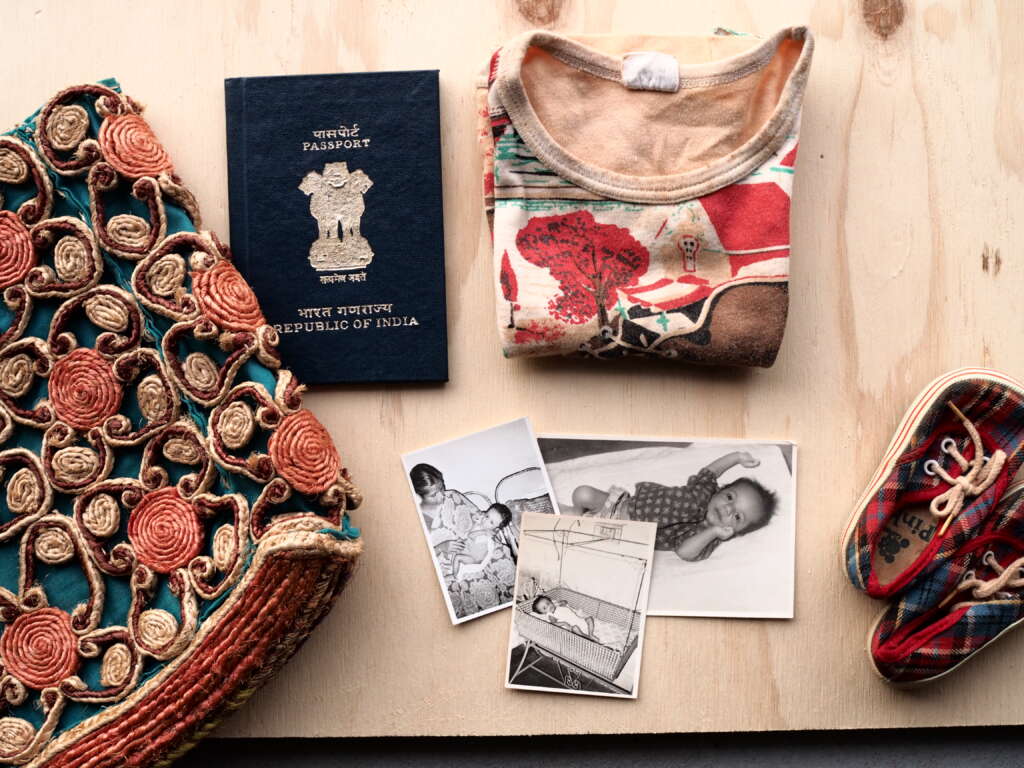

Mike Gore’s childhood memorabilia.

Feeling stressed, this Christian family prayed about the situation and the next day, the mother had a car accident while driving with her two daughters.

“She wrote the car off. But without a scratch or a bruise to anyone in the car. And then she said what was a miracle was that two days later, the day before I arrived at Sydney airport, the insurance money had been returned to her bank account. It was to the exact dollar that was needed to pay for the adoption. Not a single dollar more, not a single dollar less.”

“Church gave me a sense of identity and a sense of strength.” – Mike Gore

Mike has no memory of India and has always felt Australian. And yet he never quite fitted in at school or in Australian culture. The only place he felt at home was in church – St John’s Sutherland Anglican Church in Sydney.

“I went there as one of the Gore family, so, man, the old ladies of a morning would chastise me as much as any other kid if I stepped out of line, but every single place I went elsewhere, I was always the brown kid with these white people.

“So church gave me a sense of identity and a sense of strength. I’ve met a lot of other adopted kids who may not have had a community like a church community, and the bullying has sent them the opposite way. They’re a mess; they’re broken people these days. Whereas I feel like the church helped build in me a sense of courage.”

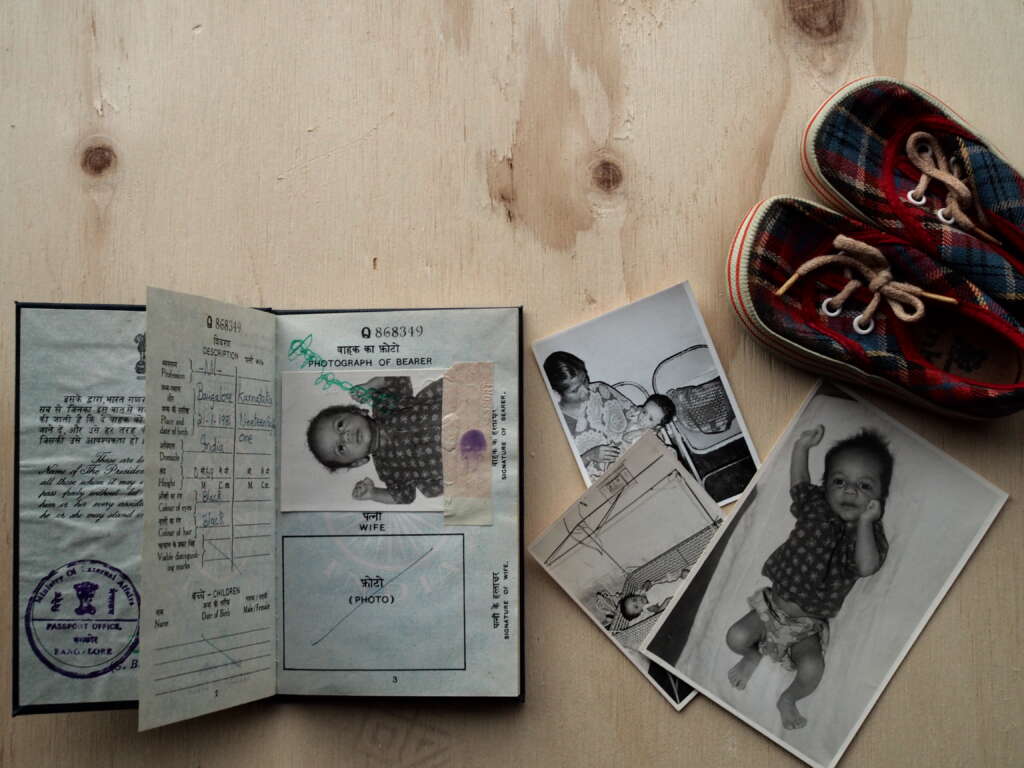

Mike Gore’s passport and other memorabilia.

Now, if this were a movie script, one would expect Mike to feel the call of his Indian heritage and possibly seek out his mother – as in the movie Lion, in which Saroo Brierley, played by Dev Patel, is adopted by a Tasmanian family and spends years tracking down the mother he was accidentally separated from.

But for Mike, the experience of going back to India when he was 18 was somewhat traumatic.

“I literally hated every moment of it, from the moment I landed to the moment I left,” he confesses.

“I didn’t feel like I fit in Australia. I desperately wanted to be seen as Australian. I was a good cricketer, a good sportsman. Where I made most of my friends was on the sporting field because I could compete with everyone else at their level, but I still never fit. The only brown kid in every single room you ever walked into, and to this day, still most of the rooms you walk into.

“I had this weird feeling that when I got off the plane in India, the motherland would metaphorically open her arms and embrace a long-lost son. It was vastly different to that. I mean, I’m dressed like a Westerner. I speak like a Westerner. I’m travelling with two Westerners. I had my passport taken. I had guns pointed at me. I was pulled out of cars on the side of roads to check who I was. People thought I was a Tamil tiger or all sorts of stuff.”

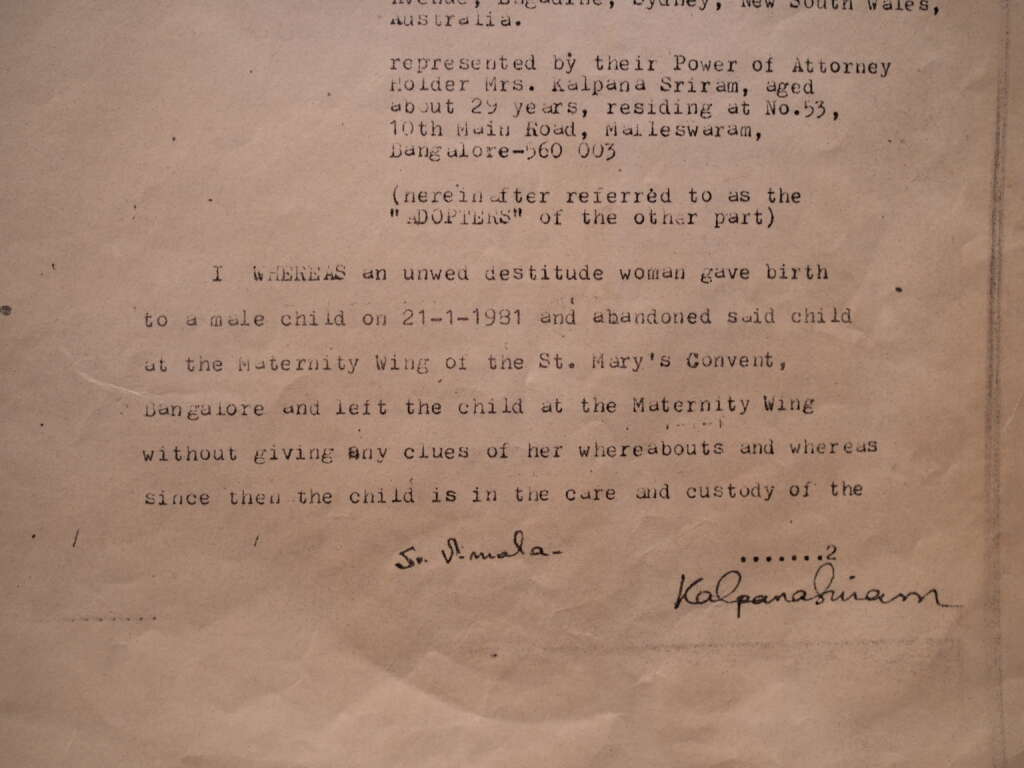

The letter that put Mike Gore in touch with his ‘fairy godmother’, Kalpana.

There is, nevertheless, a fairytale twist to the story. When Mike told his life story at an event for Open Doors, which works to support the persecuted church, he reconnected with the Indian “fairy godmother” who had changed his life.

One of the few things he had from his childhood was a letter from the orphanage with a signature on the bottom. When that was published in the Open Doors magazine, a pastor in Dapto reached out to say he recognised the signature of a woman who had helped him to adopt a child from India. He told Mike that this woman lived in Sydney and offered to reconnect them.

Mike Gore with Kalpana in Sydney on October 7. It was their second meeting in 42 years.

![]() “She was a person who escorted me out from India on the plane, handed me over to my parents, but she’s also the person who changed the court system in Chennai so I could be adopted. She is one of those fairy godmother figures that you’ve never met in your life, but in many ways, you owe your life to,” he says.

“She was a person who escorted me out from India on the plane, handed me over to my parents, but she’s also the person who changed the court system in Chennai so I could be adopted. She is one of those fairy godmother figures that you’ve never met in your life, but in many ways, you owe your life to,” he says.

Three months ago, Mike met this woman, Kalpana, for the first time as an adult. And discovered that she had facilitated the adoption of 42 children out of India.

“And just last week, I had a celebration dinner with her because she was awarded an OAM in the latest round of Honours. And she asked me to attend that dinner as one of the only children she’s in contact with that she has adopted. So it was amazing to meet her and then be able to celebrate that day with her.”

Mike Gore

To appreciate the chutzpah of Mike Gore you have to consider how he got the job at Open Doors. Rejected for both of the jobs he applied for, he got a job there by default when their first choice fell through. Three years after walking in as second choice, Mike became CEO of the organisation.

“I spent seven years as the CEO of Open Doors, travelled the world, smuggled Bibles into all sorts of weird and wonderful places. While I was at Open Doors, I – with my best friend – dreamed up this idea called Charitabl., which is like the Uber Eats of giving.”

The guiding belief behind the app is that if you make it easier for someone to buy something, the market for it grows.

“Can you imagine what could happen if we make it easier for people to give? That’s the dream with Charitabl. If we can make it easier for people to give, accessibility increases market size. If we can increase market size, reduce costs and increase the impact of every dollar raised, I’ll tell you what, we can have a really big indent on the world.”

Mike Gore with his Charitabl. app.

While Mike and his partner, Jocelyn Goto, are living off savings in the early days of the launch, they are encouraged by the positive industry response to a forward-looking technology.

“We want to be the go-to app when it comes to charitable giving in Australia. That would be our dream and vision,” says Mike.

Asked if he hopes to make a mint from Charitabl, Mike says he and Jocelyn are not interested in becoming rich and famous. They just want to make giving easier.

“If my role in life is simply to pay it forward, then I will die a happy person.”

“I’m not interested in being a millionaire. If it can make giving easier and if we were able to bring a sector together that has been historically fragmented, then it’s one of those things that Joss and I could look back on in 30 years and be proud of. We may not be millionaires, but I’ll tell you what, if we have increased the amount of money going to people at the end of it, people in beds battling leukemia, First Nations people battling living and health, sick babies …” he entreats.

“I couldn’t care less about the money. But what I do care about is that if my life story can pay it forward. Someone picked me up in a field and they dropped me off at an orphanage. Someone at an orphanage took a liking to me and smuggled me across borders. A family in Australia were selfless enough to adopt me. If my role in life is simply to pay it forward, then I will die a happy person.”

For more information about Charitabl. head to the website charitabl.org.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?