*This article contains Barbie spoilers*

By the time I saw one of the most hyped movies ever, a thousand spoilers and opinions were swirling in the back of my mind.

With Barbie, there are as many opinions as audience members. And with total earnings approaching $1.5 billion, there is clearly no shortage of audience members. The pinkest movie ever made has become a cultural moment, inspiring countless conversations about gender and beauty standards. It has also become the latest battleground in the (alluring but exhausting) ‘culture wars’, with Barbie-related social media threads always more controversial than the film itself.

So, by the time my wife and I left a remarkably mediocre pub and headed for the cinema, I had heard such irreconcilable reviews that I didn’t know what to expect.

The good

Barbie‘s weakness is also its greatest strength: its satirical presentation of gender in society.

The aimless and submissive ‘Kens’, deriving their purpose from the occasional glance of their corresponding Barbie, made me cringe. ‘Barbieland’ is an exaggerated inversion of ‘patriarchy’ in which women utterly subjugate men. I initially bristled at the portrayal of women-under-patriarchy as useless, subservient and desperate for their partner’s attention – that trope of vacuous housewives which doesn’t match a single woman I know.

But I suspect Barbieland is an intentional caricature. By identifying Kens as the lonely house-husbands, the setting becomes an evocative window into the minds of women, to the extent that the caricature matches reality. Men, in particular, are invited to empathise with women when they see the male characters taken for granted. ‘You don’t like how this feels, do you?’ Barbie asks male viewers.

There’s enough potential for good in Barbie that we – men in particular – dodge responsibility if our reaction is defensive.

The (perhaps unhelpfully titled) ‘real world’ is a caricature too (although horses absolutely should be recognised as the epitome of power and style). In Barbie and Ken’s first 30 seconds rollerblading down the Venice Beach boardwalk, Barbie (Margot Robbie) can hardly get out the words ‘real world’ before she notices leering men and catcalls, culminating in her being spanked by a stranger on the beach in broad daylight.

Admittedly, it was tempting to be defensive. This “real world” is unrealistic! Barbieland is nothing like the way I treat my wife! And there has been – praise God – tremendous progress in the treatment of women as equals inside and outside the home.

But Barbie is a chance for men to prove that we’re on board – not necessarily by embracing the movie entirely, but by demonstrating a willingness to walk in women’s shoes for a while. Like any disagreement, the point isn’t just to progress but to show compassion and understanding, to show that we get it – not in a self-congratulatory, virtue-signalling way, but in an outward-facing, relational one.

In short, there’s enough potential for good in Barbie’s presentation of ‘patriarchy’, in all its subversiveness and cinematic dramatisation, that we – men in particular – dodge responsibility if our reaction is defensive.

The bad

The problem is that while Barbie poignantly portrays the symptoms of domestic and societal conflict, its diagnosis is faulty, and its prescription is a poisoned apple.

It’s hard to pin down one problem within Barbie’s disjointed plot. Obvious candidates include the patriarchy, power and, frankly, men. With this unholy trinity of antagonists, it is easy to see how some conservative commentary was unfavourable.

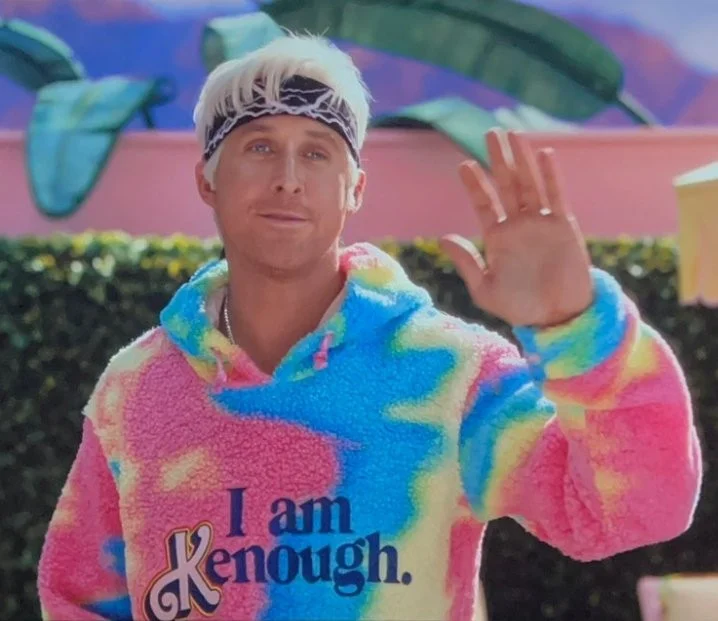

While stereotypical Barbie (Robbie), weird Barbie (Kate McKinnon) and real-world mum Gloria (America Ferrera) are likeable and three-dimensional characters, there is not a single decent man in the Barbie universe. The CEO of Mattel (Will Ferrell) is a pathetic jerk, surrounded by sycophantic minions. The Kens, including beach Ken (Ryan Gosling), go from desperate house-husbands to power-hungry tyrants, somehow devious and ruthless enough to turn Barbieland into Kendom in a few hours, but also stupid and impotent enough to be manipulated easily back into submission. Even the counter-cultural non-Ken, Alan (Michael Cera), becomes likable only by distancing himself from his cowardly counterparts.

Ryan Gosling as Ken in Barbie Warners Bros

Not only are there no good men in Barbie; there are no good relationships at all. The background of the movie is a pendulum of power, swinging back and forth from matriarchal Barbieland to patriarchal ‘real world’ to patriarchal Kendom back to matriarchal Barbieland. The glaring omission is loving relationship. There is no mutuality between Barbies and Kens, a lack symbolised by the genitalia-less, and therefore family-less, dolls; there is only animosity and power struggle. The cursed relationships of Genesis 3 are ever-present, but the mutual and fruitful dominion of Genesis 1 is nowhere to be found.

Nor is it suggested that better relationships would be a path to flourishing. Instead, the movie ends with the Barbies retaking control, intending (reluctantly?) to grant Kens gradually more rights.

It seems to me that the power struggle between men and women is merely a setting intended to provoke conversation; the real moral is more implicit. In fact, this captures one of my biggest criticisms of the film: with all its self-promotion as edgy, progressive and philosophical, the conclusion is as mainstream as it gets.

Ryan Gosling wears ‘I am Kenough’ in Barbie Warner Bros

Stereotypical Barbie and Ken both undergo transformations. Ken, initially plagued by feelings of inadequacy and desperate for Barbie’s attention, embraces a new motto: I am Kenough.

Barbie’s trouble begins with an outburst: “Do you guys ever think about dying?” The movie’s theme song, What was I made for? is a modern existentialist anthem. And when Barbie finally meets her creator (Ruth Handler, played by Rhea Perlman) in a white, ethereal realm, she is reassured that, in her climactic existential decision, she need not seek her creator’s permission or approval, but should simply make her choice and … “feel”. The only kind of loving relationship advocated in Barbie is self-love.

What is the solution to patriarchal impulses, abuse of power, the plight of women and ‘irrepressible thoughts of death’? Expressive individualism.

Yawn.

With all Barbie‘s self-promotion as edgy, progressive and philosophical, the conclusion is as mainstream as it gets.

Definitely no ugly

The underwhelming solution is not the only way Barbie overpromises and underdelivers.

One of the first signs that something is rotten in Barbieland is cellulite, appearing for the first time on Barbie’s thigh. Suddenly, her perfect plastic skin is blemished; suddenly, this iconic symbol of women’s insufficiency becomes part of the struggle.

Later, in the real world, Barbie tearfully tells an elderly, wrinkled woman, “You are so beautiful.”

“This”, director Greta Gerwig told Rolling Stone magazine, “is the heart of the movie”.

But even Gerwig can’t ignore the glaring problem. When Barbie discovers that Barbieland has become Kendom, she breaks down. She finally expresses her existential struggle in the house of ‘weird Barbie’, telling Gloria, “I’m not pretty anymore. I’m not ‘stereotypical Barbie’ pretty.”

Suddenly the film pauses, and the narrator (Helen Mirren) says, “Note to the filmmakers: Margot Robbie is the wrong person to cast if you want to make this point.”

The ‘not stereotypically pretty’ Margot Robbie as Barbie Warner Bros

But this “self-aware” joke only works because it illustrates the unmistakable hypocrisy of Barbie‘s critique of unrealistic beauty standards, a flaw that can’t be covered up with a throw-away line.

You can’t cast Margot Robbie, complaining about her unattractiveness, and subvert the stereotypical, thin, white Barbie with whom generations of women have such complicated relationships.

You can’t cast the biggest stars in your billion-dollar blockbuster with an official line of beauty merch, inspiring ‘Barbiecore’ as the trendy summer look, and critique the consumeristic beauty culture that constantly burns unattainable standards into women’s brains.

Barbie herself remains a contradiction.

Conclusion

Barbie caused backlash partly because the hype was so inescapable and the opinions were so numerous. The film was disjointed and ambiguous enough for almost any interpretation and, therefore, almost any criticism.

But the reality is that Barbie didn’t say everything – it shouldn’t have and couldn’t have. It provided a window into women’s emotional and existential lives without similarly portraying the struggles of men. And that’s okay. No story can or should be told from every perspective.

But, equally, no story should explicitly reject the unattainable standards and contradictions of female life while implicitly perpetuating all the same standards and contradictions. When all is said and done, Barbie remains a contradiction – symbolic of female empowerment and insufficiency, of progressive reimaginations of beauty and profit-driven plasticity. The conversations Barbie sparks, especially among Christians, should be nuanced, not toeing the party line but acknowledging the good, the bad and the definitely not ugly.