10 reasons you can trust the Bible

Facts, manuscripts and historical accuracy are just some of the evidence for God’s Word

There is so much scepticism about the Bible today and about Jesus, in particular, it’s difficult not to feel alarmed. The drip-drip nature of the challenges means that, just like constant, low-level criticism in relationships, many of us over time feel deflated, insecure and frightened to open our mouth. But the anxiety is psychological more than intellectual.

Our sacred texts, and especially those surrounding Jesus, pass the test of history with flying colours.

Frankly, I don’t think we need to know any of what follows in order to be a fulfilled and confident Christian. The word of God stands all on its own. But since so many of today’s criticisms of Christianity are historical in nature, it seems reasonable to me to offer these

ten reasons not to panic about Bible scepticism.

1. We should expect historical questions because Christianity is historical

The Bible’s New Testament is different from the Scriptures of other world religions.

The Koran claims to be a direct revelation from God, entirely devoid of historical markers and claims. The Hindu Vedas and Upanishads, and the Buddhist Tripitaka are the same. One can believe these writings but there is no way to verify their contents.

We should take questions that zero in on history as a kind of compliment

That makes being a Muslim, Hindu or Buddhist quite “safe” because their sacred books are immune to historical criticism. But it also means onlookers have no way to “test” the core content of these faiths.

The Bible is different. The heart of Christian faith is a series of events recorded in a collection of histories and letters, gathered together in the Bible. As soon as you say, “This man Jesus said … and did …” you are making claims about history.

It is only to be expected, then, that others would ask, “How do you know that happened?”

We should take questions that zero in on history as a kind of compliment and a sign that our questioners understand the nature of our claims.

2. The gospels are now widely recognised by secular experts as historical biographies

There was a time when people read the gospel accounts as “myth.” The great German scholar David Friedrich Strauss (1808-1874) argued that the narratives of Jesus were never intended to be read as history but were only meant as poetical and metaphorical accounts of the spiritual and moral life. Jesus didn’t actually give sight to the blind, for example; such stories were really only about the religious “insight” we gain when we listen to the wisdom of Christ.

This view may persist in the popular mind, but it has disappeared from scholarship. Between the 1970s and ’90s, a consensus emerged among experts that the gospels have to be read as “biographies” of a real individual. They share many similarities – in length, structure, design and content – with the 20-30 other biographies from the period. So they have to be read as real-world accounts of the sayings and deeds of a first-century individual.

3. The New Testament contains a “collection” of independent evidence about Jesus

The New Testament seems like one book today. It has its own ISBN, after all! But, originally, many of these texts were written independently of each other.

The Gospel of Mark was written without a knowledge of what was in the letters of Paul. Paul himself wrote without any knowledge of the Gospel of Mark. James wrote his letter without possessing copies of Mark or Paul’s epistles. Here, then, are three separate sources, only later (in the second century) brought into a single volume called the New Testament.

Do we have more than one source testifying to the event?

There are even sources within individual gospels, according to most secular experts today. Luke in his opening line tells us, “Many have undertaken to draw up an account of the things that have been fulfilled among us.” Today, scholars reckon they can detect at least three separate sources in his gospel. Overall, then, there are between five and seven sources in the New Testament which haven’t been simply copied from each other. The point of the observation – from the historical point of view – is that this fulfils one of the most important “tests” that contemporary historians apply when trying to work out what happened in the past: Do we have more than one source testifying to the event? In the case of Jesus, we have between five and seven different sources saying roughly the same thing about him. That puts the broad outline of Jesus’ life beyond reasonable doubt for most specialists working today.

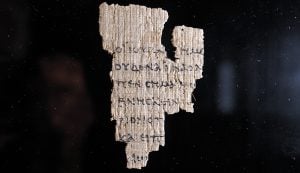

“Papyrus 52” is a fragment of John’s Gospel, kept at John Rylands Library in Manchester, England. CPX/Allan Dowthwaite

4. The New Testament sources are relatively early

In ancient history, scholars are used to assessing sources written many decades, or even centuries, after the events under investigation. That’s the norm.

Rarely, if ever, do we find sources contemporaneous with events. So, for example, our first detailed biographical account of Alexander the Great (356-323 BC) was written by Polybius about 120 years after Alexander’s death. Likewise, the most important account of Emperor Tiberius, who ruled when Jesus lived, was penned by Tacitus some 80 years after his death.

The New Testament documents, on the other hand, are significantly earlier. The gospel source known as Q and the earliest letters of Paul come from around the year 50, just 20 years after Jesus’ death. Several more documents (like Mark and James) come from the ’60s, just 30 or so years after Jesus. And the latest New Testament document in the opinion of secular scholars, the Gospel of John, was probably written around the year 90, just 60 years after the event. (Personally, I think John is much earlier, but I’m giving the dates used by most secular specialists.) That means that the latest New Testament record we have for Jesus is still earlier than the best record we have for Emperor Tiberius who lived at the same time.

5. Before the New Testament was written, the words and deeds of Jesus were preserved by oral tradition

In the ancient world only about 10-15 per cent of the population could read. So people’s first instinct when important things happened wasn’t to write them down. That only preserved the news for a small, elite subset of the population. If you wanted the masses to know something – whether an important military event, a summary of a philosophical system or a particular teacher’s sayings – you relied on what scholars call “oral tradition.”

In our instant, media-saturated world, we expect things to be on Twitter or our news feeds within minutes of them happening. But that’s not how the first century worked. We know beyond doubting that ancient Greeks, Romans and Jews were well practised in the art of memorisation and rehearsal of important material. (We have lost this art, to our great detriment.)

In reality, it is surprising that we have so much Christian material written down so soon.

For example, initiates in the philosophy of Epicurus, one of the most popular schools in the period, had to learn by heart about 2000 words of complex philosophical sayings of the founder of the movement. This wasn’t unusual. Jewish rabbis made similar demands of their disciples, and all of the evidence points to Jesus insisting upon the same with his disciples. These disciples then appointed others – known as “teachers” – to ensure that the same material was passed on and preserved in the growing churches. In reality, it is surprising that we have so much Christian material written down so soon.

6. Non-Christian writings confirm the broad outline of Jesus’ life

Scraps of information about Jesus can be found in writers with no Christian faith at all. Tacitus left us a passing criticism of the Christians that mentions Jesus’ title (Christ), time and place and the circumstances of his death. The Jewish writer Josephus mentions Jesus on two occasions. If you read the “scepti-net” you will find many ardent atheists today dismiss Josephus’ evidence as a wholesale Christian forgery. They are confused. The consensus today is that one of Josephus’ two paragraphs about Jesus has indeed been “improved” by a Christian copyist in an effort to turn “a wise man” into “more than a man.” But once these additions are removed, the paragraph makes perfect sense as a neutral, passing remark about Jesus from a non-Christian Jew.

And several of Josephus’ comments make no sense if all of them were a Christian invention: for example, he sounds surprised that “the tribe of Christians has still to this day not disappeared,” which suggests he expected Christians to dwindle any day now. In any case, Josephus’ other mention of Jesus falls under no suspicion. He certainly knew of “the one called Christ.” “The fact that Jesus existed, that he was crucified under Pontius Pilate … seems to be part of the bedrock of historical tradition,” writes Christopher Tuckett, an Oxford University professor and no friend to Christian apologetics. “If nothing else, the non-Christian evidence can provide us with certainty on that score.”

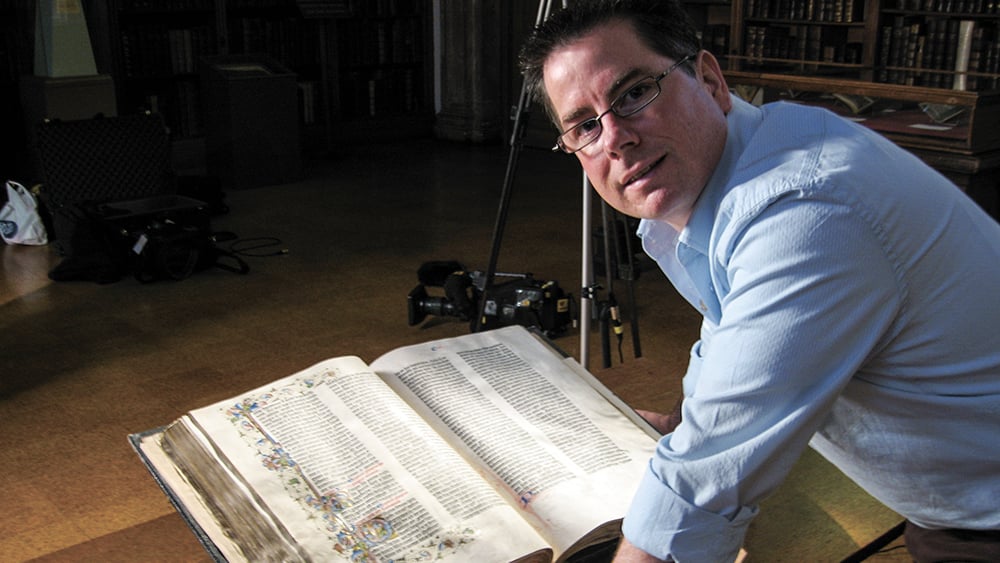

John Dickson consults a medieval manuscript of Josephus in Cambridge, England. CPX/Allan Dowthwaite

7. Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence

Despite the range and early date of our evidence for Jesus, there is still a great deal that cannot be corroborated by other sources. Some might see this as reason for concern. Surely events as significant as those in the Bible should be reported by everyone in the ancient world, right? Not really.

This is one of those occasions where the study of history is very different from the study of yesterday’s news. 99 per cent of the written material of the first century is simply gone. We know of hundreds of writers – mentioned by the authors we do have – whose writings are completely lost from history. It is just a painful reality of ancient historical research that we are trying to piece together the past with less than 1 per cent of the relevant material. Loads of things can be affirmed from 1 per cent of evidence, but it’s not advisable to deny things when 99 per cent of the evidence is missing.

For example, there is no evidence outside of Luke 2 for a census of the Roman world around the time of the birth of Jesus. But with 99 per cent of the documentation missing, it would be unwise to say with confidence that Luke made a mistake. His evidence counts as evidence, even if it is not able to be corroborated.

“It is an elementary error to suppose that the unmentioned did not exist.” – Graham Stanton

I remember debating someone from the Rationalist Society years ago. He demanded to know why we don’t have any mention of Jesus in any of the correspondence between governor Pontius Pilate and Emperor Tiberius. Governors were indeed required to issue constant reports to their superiors, so the absence of evidence is significant, he thought. But what he didn’t know (how, I have no idea) is that we don’t have a single piece of correspondence from Pontius Pilate to anyone. In fact, we don’t have a single piece of correspondence from Emperor Tiberius to anyone. Thousands of documents must have flowed to and from Rome and Jerusalem, but none of them survives. The absence of evidence from Pilate about Jesus is not evidence of the absence of Jesus from history. Scholars are usually far more cautious about such things. As Cambridge University’s famous Graham Stanton once put it, “every student of ancient history is aware, it is an elementary error to suppose that the unmentioned did not exist.”

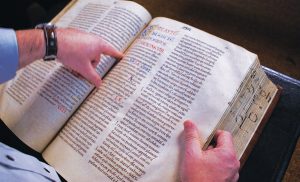

8. The New Testament is probably the best preserved text of all ancient history

A rumour has spread that the text of the New Testament has not been reliably passed down through the centuries. It was copied from one document to another document, translated from one dead language to another dead language, and eventually it ended up in our pew Bibles. Who knows if what we read today is what the original writers first wrote!? Well, in fact we do know. The more manuscript copies of an ancient text we have, the better able we are to determine what was in the original document. Mistakes and changes certainly happen – in all ancient copies of documents – but if you only have, say, two or three copies of a document and they vary from one another here and there, it is quite difficult to work out which wording is original and which is a variation.

So how does the New Testament fare in the copying stakes? Better than any other ancient writing! Let me offer the fairest comparison imaginable. The most celebrated epic poem of Roman history is the Aeneid, by Virgil (it runs about the same length as the four gospels combined). It was so popular, it was copied over and over. And it is now considered the best preserved Latin text we have from ancient times. It has come down to us in the following manuscript copies:

- Three complete or near-complete copies

- Seven partial manuscripts (a partial manuscript could include 50 or more pages of writing)

- 20 papyrus fragments (which might just be a page or two)

Compare this with the New Testament manuscript copies:

- Four complete or near-complete copies (very comparable to the Aeneid)

- 340 partial manuscripts (far more than the Aeneid. And keep in mind that “partial” can include manuscripts which contain entire gospels or several of Paul’s letters)

- 1000s of papyrus fragments (scraps of paper with short or long passages from the New Testament)

Because of the overwhelming number of copies of the New Testament, we are far more easily able to spot the variations and arrive at a high degree of confidence about the original text.

9. Archaeology confirms important facts about the world of Jesus

Scores of digs are going on around Israel. Some are uncovering vital information about the world of Jesus. There are numerous chance findings that “prove” bits and pieces of the gospels – the Pool of Siloam in 2004; a house from Jesus’ home town of Nazareth in 2009; an early first-century synagogue on the shore of Lake Galilee in 2009 – but they are not the most significant results of archaeology.

Two crucial features of the gospels have been verified by recent findings in Galilee and Judea. First, the thoroughly Jewish character of Lower Galilee (where Jesus was from) is confirmed by the discovery of Jewish pots, ritual baths and the absence of pig bones (a forbidden food for Jews) in the rubbish dumps of these towns. Some scholars used to claim that the Jewish nature of the story of Jesus didn’t fit with the more Gentile physical environment of Galilee. They were wrong.

And, yet, secondly, the gospels were written in Greek. How could an authentically Jewish story end up in the “pagan” language (instead of Aramaic)? And does this mean there is a large cultural gap between the Jewish Jesus of Galilee and the Greek language of the later gospels? Archaeology has helped here, too. It is now known that a significant proportion of Jerusalem’s population spoke Greek as a first language. Scraps of documents and inscriptions in Greek make clear that the international “pagan” language was very widely used by Jews inside and outside the holy land.

The discovery of a first-century Greek-speaking synagogue right next to the Jerusalem temple suggests that some of Jesus’ first followers in Jerusalem would have had good Greek (as well as Aramaic). The stories and teachings of Jesus would have been translated and communicated in Greek from the very beginning.

10. Jesus is more trustworthy than we are trusting

In the opening paragraph of his Gospel, Luke reveals the historical nature of his subject. He mentions his earlier sources, insists that the information comes from eyewitnesses, and claims to have “investigated everything from the beginning.” He rounds off his introductory remarks with a highly significant statement about his goal: “so that you may know the certainty of the things you have been taught.”

The word “certainty” is the Greek term asphalaia, from which we get the English “asphalt,” that mixture of bituminous pitch with sand or gravel that we make roads with. The term means firmness, safety, stability. While it is possible Luke just means he wants readers to arrive at cognitive “certainty” about Jesus, the precise wording suggests something different.

I no longer stress about doubts.

He wants readers to perceive how firm Jesus is. In other words, this isn’t about us having no intellectual doubts. It’s about us developing a sense (however strong that sense might be) of the dependability of Christ himself.

The difference may seem subtle, but it is significant. Having spent decades reading and researching ancient history and the historical Jesus, I have come to believe Jesus is more reliable than my subjective feelings of confidence.

Our personal confidence in the Bible can ebb and flow. It is affected by whatever documentary we last saw on the subject, or by what our friends think of Christianity, or just by how much sleep we had last night!

But I no longer stress about doubts. When a question arises in my mind about the history behind Scripture, I assess whether it is a doubt of substance or just subjective feeling of lack of confidence. If it’s the former, I do a little more digging; and I have found through the years that there are always answers to the intellectual questions. If it is the latter, I just relax and remind myself that the gospel of Jesus is far more substantial and solid than anything the discipline of history can uncover and far more trustworthy than I am trusting.

John Dickson is Founding Director of the Centre for Public Christianity and Honorary Fellow of the Department of Ancient History at Macquarie University.