Shorty Brown reckons he was born to be a soldier. He was just five years old when he was inspired by the sight of a soldier standing at a bus stop with a slouch hat and khaki and a kit bag.

“I looked at this man who looked a million feet tall and a great specimen of a man, and I said, ‘That’s what I want to do,’” says the Vietnam veteran who spent 20 years as a soldier and 24 years as an army chaplain.

“Some people should never be soldiers, and some people were born to be soldiers. At the age of five, I knew what I wanted to do. I suppose there’s that ancient warrior that flows through your blood. On my father’s side, there’s always been people in the military.”

Richard gained his nickname when he joined the army in 1965. In Australia, when someone is called Shorty, you don’t know if it’s because they’re really tall or really short. This Shorty – whose Christian name is Richard – was rejected for being too short when he first tried to join the army as an apprentice (he measures only 4ft 11½ inches or 151cm). But when Australia first introduced conscription for the Vietnam War, he decided to have another go.

Shorty could easily have been one of those who didn’t make it out alive …

“When the call up came, I didn’t fill out the paperwork and my father said, ‘You should register.’ I said, ‘I’m too short.’ He said, ‘You should still do it.’ So, I did. I was working as a butcher up in Guyra, New South Wales. I went and had my medical interview and the doctor there, Dr Williams, said, ‘How tall are you?’ I said, ‘I’m five foot two.’ And that’s how I got into the army.”

Speaking to Eternity to reflect on the 50th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War, Shorty said he remembers the fellows who he served with who died during the war and those who have since died.

Shorty could easily have been one of those who didn’t make it out alive. After getting his boots in 1965 and his initial training at the NSW base at Kapooka, Shorty was posted to Vietnam with the infantry corps 6th Battalion, in the 12th Platoon Delta Company, 6th Royal Australian Regiment.

On August 18, 1966, he was part of the famous Battle of Long Tan, where the 108 troops of D Company came upon an enemy force of 2500 North Vietnamese and Viet Cong soldiers. Seventeen members of D Coy died in the battle, along with another Australian soldier who was part of the battle.

Shorty (Richard) Brown on Anzac Day with his medals: Military Medal; Active Service Medal 1945-1975 Vietnam; Vietnam Service Medal; Australian Active Service medal 1975 ICAT; Afghanistan Medal; Australian Service Medal Solomon Is; 3 long service medals; Australian Defence Medal; National Service Medal; Republic of Vietnam Campaign Star; NATO Medal ISAF. Infantry Combat Badge and 3 Unit Citations for the Battle of Long Tan; Australian Unit Citation for Gallantry; US Presidential Unit Citation; and the Vietnam Unit Citation with Palm for Gallantry Citation.

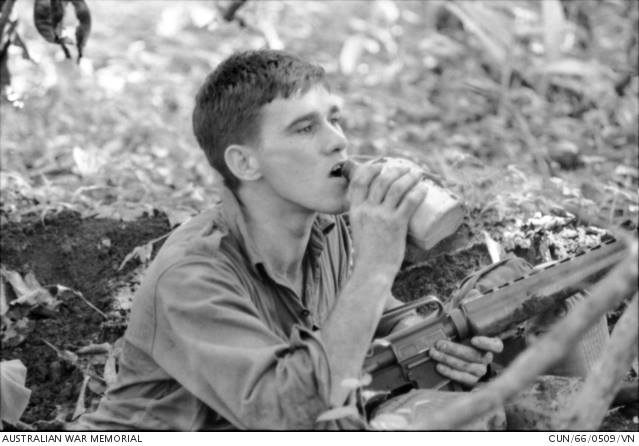

Shorty, a forward scout with 12 Platoon, ended up lying in the mud in a rubber plantation after D Coy was sent to track down a mortar crew who had fired on the Australians’ base at Nui Dat. They initially didn’t realise the enemy force was much bigger than D Coy. But they knew they were in trouble as the battle flared between rifles, machine guns, mortars and artillery shells, deafening them.

To worsen the situation, they were hit by a tropical downpour that reduced visibility to about 20 metres, and the company ran low on ammunition. D Coy was finally saved by reinforcements of more troops in Armoured Personnel Carriers. The enemy withdrew as the afternoon turned into night, and the battlefield fell silent. And Shorty was thankful to still be alive.

But for Shorty, that was not even his most frightening experience. That came during his first contact with the Viet Cong when a machine gun fired over him.

“A lady came down this track with an empty basket, going back to a village, and so my tour commander sent me up to see what she was doing. When I got up there, I looked, and four enemies jumped up and fired, and my rifle jammed, so I hit the ground. My big mate, who since passed away, a fella called Peter Dettman, who was a machine gunner, fired right across over my body because he thought I was dead. It was pretty scary because I’m getting bullets one way and bullets the other way.”

“For many years I used to see the faces of the families [in photos] they carried in their pockets, which we saw when we had to search their bodies.” – Shorty Brown

While those people got away, Shorty acknowledges that he did take lives during two tours of duty in Vietnam.

“That was mainly on my second tour, but for many years I used to see the faces of the families [in photos] they carried in their pockets, which we saw when we had to search their bodies,” he says.

He was wounded during his second tour when, as a corporal in charge of a section of soldiers, he moved his section forward to take an enemy pit. “We were moving forward, but we were fired upon from the flank and I realised if I went further, I would’ve exposed all my section to this machine gun. We stayed in dead ground where they couldn’t get us, so they fired rocket-propelled grenades into the trees. When they hit the tree, the grenades burst and a lot of my section were wounded by shrapnel, so I withdrew my section and got the wounded fellows back.”

Recovering at home, Shorty was posted to the Jungle Training Centre at Canungra, Queensland, as a sergeant, and he joined the 8th Battalion. It was here he was converted at a baptism service.

“When I got wounded on my second tour, my wife, who was a Christian, wanted to take me to church to give thanks to God, and I just said, ‘There’s no such thing,’” he recalls.

“My neighbour’s son, Robert was being baptised and I was going to get the barbecue ready. And my wife said, ‘Well, you better change and get ready for the church.’ And I said, ‘No, I’ve got the barbecue.’ And she said, ‘The barbecue isn’t the baptism service – you’re coming.’ So I went to church and the priest held the child up and said, ‘This child is the heir of the kingdom of God!’ Something inside me said, ‘And so are you.’”

The first thing his mates noticed after his conversion was that he wasn’t drinking anymore.

Struggling with that voice from God, the next Sunday, Shorty decided to go to church by himself and when the communion service started, he went forward to receive the sacraments.

“When I did, I suddenly remembered the priest who trained me for confirmation when I was about 12 – it all came back to me, and I gave my life to Jesus there. I drove from there to the first traffic light up in Brisbane, and ‘I thought I’ve got it all made’ – because my marriage at that time wasn’t the best. But God said to me, ‘But you’re a drunk.’ So from then, I realised I needed not just to give my life to Jesus but to ask for help. That’s how I became a Christian.”

Before he went to Vietnam, Shorty was already drinking a litre of wine most nights, and his drinking had only become heavier under the stress of being on active duty. So the first thing his mates noticed after his conversion was that he wasn’t drinking anymore.

“I said, ‘No, I don’t need to … And I realised through the Holy Spirit I had victory over a problem that was obviously caused by my service in Vietnam.”

A lasting effect of fighting in the Vietnam War is that sudden noises frighten Shorty even today.

“If someone walked behind me and I didn’t realise it, it would frighten the daylights out of me,” he said. “You really don’t want to know what it was like.”

Paul Large from Coolah in rural New South Wales who departed for the Vietnam War on his 21st birthday. He was killed in action 10 weeks later at the Battle of Long Tan on 18 August 1966. Australian War Memorial

Another enduring legacy of the conflict is Shorty’s reluctance to make close friends for fear of losing them.

“I used to have a friend called Paul Large. He was a forward scout like I was, and he got killed at Long Tan. He’s buried at Coolah. Because of his death, I found it very hard to continue on with the friendships I had,” he says.

“I did not want to be hurt again. Even today, I’ve got lots of friends, but they’re not close.”

It was the voice of God again that prompted Shorty to become a chaplain.

“I was taking the garbage bins out and as I was putting them on the road to go to work, I just felt God say to me, ‘I want you to serve full time.’”

He went on to do theological training in Brisbane and was ordained as a deacon in 1984 and to the priesthood the following year.

“My first appointment was in Murwillumbah and my boss was my first army chaplain in Vietnam. So then I became an army chaplain part time, went back in full time and then, when I got to retirement age, I went back to the reserves. Then they called me back and sent me off to Afghanistan and I said ‘no more’. So I did 44 years service in the army, 20 years as a soldier and 24 years as a chaplain.”

Thinking about the 50th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War, Shorty gets emotional thinking of his friends who have died and their families.

“I’ve got three daughters and four granddaughters – and when they come home at Christmas time, I get a bit emotional. I look at my daughters and my granddaughters and think how fortunate I am. And I think of other families that don’t have that. And so when I do the RSL poppy service, I find it very inspiring to share with the widow, the legatee, what their husbands experienced. I’ve never served with their husbands, but I know of their service. Pray for me that I will continue to care for war widows in a loving way. And gently introduce Jesus into their lives.”

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?