Bioethicists: Aussie model embryo research highlights need for overdue ethics conversation

The work of Australian researchers who have developed a ‘model embryo’ will “revolutionise research into the causes of early miscarriage, infertility and the study of early human development”, according to Monash University, the home of the scientists behind the groundbreaking research.

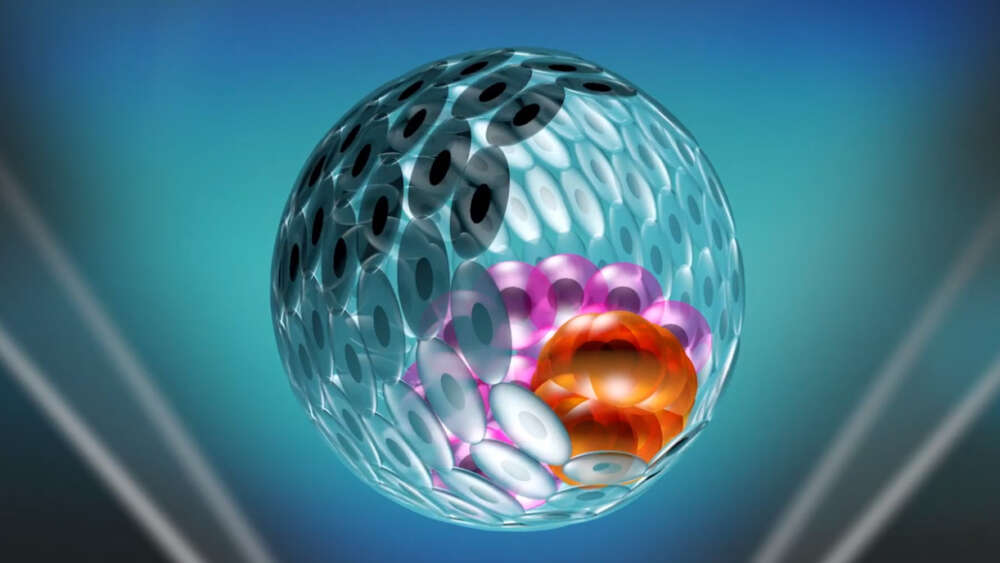

Earlier this month, a team led by Professor Jose Polo published their research in the journal Nature, outlining how they reprogrammed skin cells into a 3D cellular structure similar to human blastocysts. In a natural pregnancy, a blastocyst is an early stage embryo that forms a few days after fertilisation. Some of the cells in the blastocyst will help to form the foetus, while others help to form the placenta.

Can the creation of model human embryos lead us to ask deeper questions?

Bioethicists: Aussie model embryo research highlights need for overdue ethics conversation

The researchers are calling their model embryos ‘iBlastoids’ stressed that these embryos, while closely mimicking the early human embryo, are not the same as human embryos.

“An iBlastoid is not generated using an egg or sperm, and has limited ability to develop beyond the first few days,” the researchers said.

In an interview with the Sydney Morning Herald, Professor Polo said there needed to be a conversation about the status of these new creations, including what research can ethically be performed on them, and how far they can be allowed to develop. So far, the researchers have not allowed the model embryo to grow past the 11-day mark. Polo said that while he wasn’t sure what religious leaders might think of his research, he did not consider that he had “created life”.

“This is clearly early days, it is right to tread carefully as we approach new frontiers” – Anglican Archbishop of Sydney Glenn Davies

Anglican Archbishop of Sydney Glenn Davies commended the researchers for their ethical concerns on ABC Radio last week, saying “This is clearly early days, it is right to tread carefully as we approach new frontiers.”

“I cannot see that there’s an ethical problem. It’s not embryonic research as we normally know it. Embryonic cells and stem cells for example, we’ve always had difficulties with that by using aborted material, but adult stem cells, we have always supported that.”

Debate about the ethics of using human embryos for research began in earnest in the late 1980s. Professor Margaret Somerville, a bioethicist at the University of Notre Dame in Sydney was part of those debates.

“Around those times there was talk of creating human embryo manufacturing plants – creating embryos just for scientific research,” Professor Somerville told Eternity. “The research had the potential of great benefit to a lot of people, but mostly it was considered unethical.”

“In Canada, where I was based at the time, you could only do research on an embryo if it was meant to be for the benefit of that embryo. You couldn’t use the embryo as a product,” she said.

“… you really have to start with respect for human life. It’s probably the single most important value in our society” – Professor Margaret Somerville

“In debates like this, you really have to start with respect for human life. It’s probably the single most important value in our society.”

Stem cell research at the time involved taking the stem cells from the human embryos, which meant killing it. With limits placed on human embryo research, other methods were developed for stem cell research that did not involve embryos. The Catholic Church in Australia even funded research into the therapeutic potential of stem cells that are not derived from human embryos.

Research on the early stages of human life is tricky, with ethical restrictions on studying human embryos. Studying human embryogenesis in the lab could lead to better infertility treatments or contraceptives, more-effective and safer in vitro fertilization (IVF) procedures, the prevention and treatment of developmental disorders, and even the creation of organs for people who need a transplant.

But with the publication of this new research, the question becomes: what is the ethical status of a model embryo?

While the Monash researchers maintain the model embryo could never go on to create a human life, other developmental biology experts and bioethicists say it won’t be long until the kinks are resolved.

“I’m sure it makes anyone who is morally serious nervous when people start creating structures in a petri dish that are this close to being early human beings,” Dr Daniel Sulmasy, a bioethicist at Georgetown University, told NPR.

“They’re not quite there yet, and so that’s good. But the more they press the envelope, the more nervous I think anybody would get that people are trying to sort of create human beings in a test tube,” Sulmasy says.

Professor Margaret Somerville told Eternity that part of the problem is that no one is sure what the model embryos really are. She warns that society must be wary of the manipulation of language that researchers can often use when they are trying to study ethically grey areas.

“We need to watch out. Sometimes language can confuse the real issue. We had people in the early days of human embryo research label an embryo as a ‘pre-embryo’ and arguing it wasn’t an embryo until 14 days after conception, because before that time it could still split and become twins or triplets, so you couldn’t say it was one ‘human person’. Language is slippery. There can be a lot of manipulation.”

“We should be suspicious of those who rush to characterise them as no embryo at all, particularly when they stand to benefit from this type of dehumanisation” – Catholic Archbishop of Sydney Anthony Fisher

In an opinion piece for The Australian newspaper, Catholic Archbishop of Sydney Anthony Fisher questioned the researchers labelling of the model embryo as an ‘iBlastoid’: “Is this label just a matter of convenience, masking legitimate questions about their identity and making them sound more like the latest Apple product and less than a human being worthy of respect or protection?”

Fisher, who also holds a doctorate in bioethics from the University of Oxford, wrote, “As the saying goes: ‘If it looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, it’s probably a duck.

“So, too, with an embryo: if it has human genes, develops as a human being develops, and does the things a human embryo does, it’s probably an embryonic human.”

However, Fisher conceded that if the model embryos do not have such a development trajectory, then they might not be bona fide embryos at all.

“In that case, there might be ethical uses for them, and we would support and encourage such ethical use.”

But, he said, “we should be suspicious of those who rush to characterise them as no embryo at all, particularly when they stand to benefit from this type of dehumanisation.”

While the Monash team said the creation of their model embryo was an accident, Archbishop Fisher was not convinced. Model embryo research has been ongoing for at least five years, with researchers in the United States making significant steps forward using mouse models. In 2018, a group of biologists involved in this research wrote an editorial in the Nature journal saying “it now seems feasible that stem cells can be developed into models that are almost indistinguishable from embryos in the lab. Such models can also be transferred into the womb of a mouse, where they begin to implant.”

They urged for more regulation, in particular to ban the use of model embryos to try and start a pregnancy.

“We urge regulators to ban the use of stem-cell based entities for reproductive purposes,” they wrote.

As the pace of scientific research continues to intensify, an international conversation is needed to “ensure that promising avenues for research proceed with due caution, especially given the complexity of the science.”

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?