This is the second part in Eternity’s interview with Dr Di Rayson. Click here to read Part 1: ‘What would Bonhoeffer do?’ is the wrong question and Part 3: Bonhoeffer’s ‘Religionless Christianity’ and Christian responsibility.

Worldly Christianity

Dietrich Bonhoeffer was very interested in the “worldliness” of Christianity, Dr Dianne Rayson says. He understood that he was living in (or, at the very least was entering, after the atrocities of World War II) a different age when the church was no longer the centre of the village or the driver of how communities would function. But he saw the role of the church to be very much engaged in the world around it.

'What would Bonhoeffer do?' is the wrong question

Bonhoeffer's ‘Religionless Christianity’ and Christian responsibility

“So if that’s the case, when we think about praying the Lord’s Prayer, when we pray ‘Thy kingdom come’ we’re really agreeing with God that we will participate in the manifestation of that kingdom here and now in this world,” she explains.

“In Bonhoeffer’s mind – and I would agree – this is not a prayer for a future ideal, or another place or another time after we die (heaven). This is much more about [the question of] ‘How do we bring the love of God and the reconciliation of God to the world in which we live?’ And you can see that through the parables that Jesus tells, and obviously in Jesus’ own life story.”

To Bonhoeffer, being “other worldly” meant that your focus was on another time and place, and that would distract you from the need that is before you. But he was also concerned about Christians being too engaged with the world – too secular – without appreciating the mystical, spiritual and the transcendent aspects of the world.

The better way, he suggested, was to engage in the world for the sake of Christ.

“We [humanity] are sentient and clearly have ‘the power’ because we’ve utilised that power to harm creation,” Rayson explains. “So we have power, but the question is, how do we use the power?

“Do we use that to participate in Christ’s reconciliation in the world? Or do we use it to continue to harm the world?”

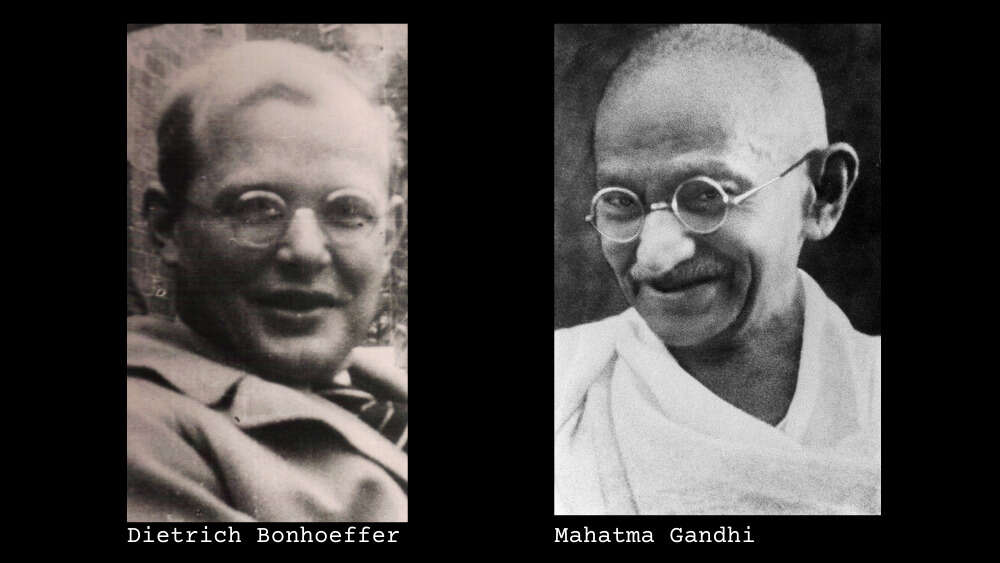

“You really wonder what might have happened had they sat together and conversed,” Rayson muses. “He was very interested in Gandhi’s nonviolent resistance …”

For Bonhoeffer, that meant walking gently and humbly upon the earth – an idea that he knew was not unique to Christianity but featured in different religions, too.

“The notion of walking gently is a really Jain and Hindu notion that (Mahatma) Gandhi made famous,” Rayson says. (Note: Jainism is traditionally known as Jain Dharma. It is an ancient Indian religion that traces its spiritual ideas and history through a succession of 24 leaders. Its main religious premises are non-violence, many-sidedness, non-attachment and asceticism – i.e. abstinence from sensual pleasures.)

Rayson says it is clear that Bonhoeffer was really interested in Gandhi, from the few pieces of correspondence between them which have survived. Bonhoeffer had even received an invitation to go, work, study and live with Gandhi in India. But though he made several attempts to get there, in the end it never happened.

“You really wonder what might have happened had they sat together and conversed,” Rayson muses.

“He was very interested in Gandhi’s nonviolent resistance, the way Gandhi conducted himself in the political arena, and how much Christians – particularly the Deutsche Christen (the German Christian Church during the war years) – had to learn from people outside of Christianity … [Bonhoeffer said they] were actually more Christian than the so-called Christians around him.”

“So he certainly wasn’t averse to thinking broadly about how the transcendent appears to other cultural contexts.”

So what exactly does this Gandhian idea of walking gently and humbly upon the earth mean?

Rayson says it is “that we walk gently metaphorically, so that we have as little impact on the world as possible. That we pollute as little as possible. That we perhaps think about the animals that are being slaughtered for human consumption in an unethical way.”

She provides examples.

“So we might choose not to eat meat. Or we consider how we clothe ourselves – do we clothe ourselves with garments made in very substandard conditions by people with very little power in the greater scheme of things? All of these things are metaphorical ways that we might walk gently.”

“But in Jain and Hindu understandings, it’s also like a really literal meaning that Earth actually is sentient to some extent or feels the weight of bodies on the surface of Earth. And when we walk with this consideration of the impact that we make, as we walk on Earth herself, we then tend to walk differently and to behave differently because we see ourselves as part of this one living organism.”

Bonhoeffer and the rise of Christian nationalism

Rayson explains that Gandhi’s “walking gently and humbly upon the earth” could also have other resonances when shaped through Bonhoeffer’s Christian lens.

“Bonhoeffer’s use of terms such as ‘being grounded’, ‘standing firm’ and ‘having one’s feet on the ground’ in the Tegel ‘Drama’ and ‘After Ten Years’ … could also be Bonhoeffer ‘subverting’ the Nazi use of the slogan, ‘Blut und Boden’ (blood and soil) that had seduced the mainstream church,” Rayson writes in her PhD thesis.

She explains.

“For the Deutsche Christens – the German Christian Church who sided with the national socialists – there was a really strong element of Christian purity which then sort of morphed into racial purity.”

“So there’s two things: the idea that we are German, and that this is the soil of our fathers – the fatherland where we’ve been born and we’ve been returned to this soil.”

So, it seems Bonhoeffer was opposing the nationalism that grew up around the folk myth of the purity of the German blood by noting that ‘it’s not for us to say this since our religion derives from the East. It’s not really a European religion to start with, we’re a middle Eastern religion.’”

Bonhoeffer was “a proud German – a product of his own history and context” Rayson says – but with an important caveat. “He was certainly opposed to layering nationalism with a brand of Christianity which was inauthentic, in his mind.”

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?