Do we need revival today?

Aziza Green explores the what, why, how and when of revival.

Eternity is revisiting some of the stories our staff writers most loved writing.

Aziza Green, Content Producer for Eternity, chose this story. She says, “Researching and writing this story allowed me to do a deep dive into the remarkable history of revival in Australia and beyond. I was fortunate enough to interview Professor Stuart Piggin (Professor of History at Macquarie University), Pastor Mark Sayers (Senior Leader of Red Church in Victoria) and Pastor Jemima Varughese (Senior Associate at multi-site megachurch, Kingdomcity), who have each passionately studied revival over many years.

“Talking about revival, studying revival and praying for revival ignited a fresh hunger in me, not for signs and wonders, but for unity and the transformation of whole communities for the glory of God.”

When a small chapel service at Asbury University sparked a two-week outpouring of the Holy Spirit earlier this year, it got a lot of people talking about revival.

But revivals divide as much as they unite, attracting the attention of seekers and critics. Eternity sat down with three ‘revival experts’ – Professor Stuart Piggin (Conjoint Associate Professor of History at Macquarie University), Pastor Mark Sayers (Senior Leader of Red Church in Victoria) and Pastor Jemima Varughese (Senior Associate at multi-site megachurch, Kingdomcity) – to learn about revival and what it means for the 21st-century church.

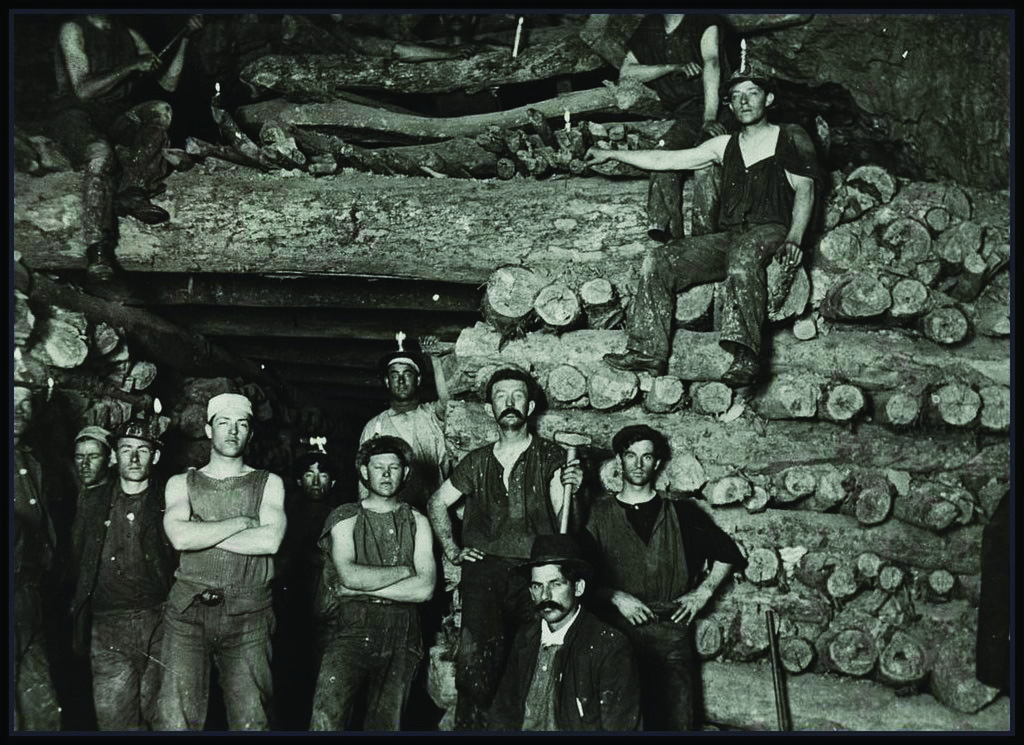

Prof Stuart Piggin is the author of seven books, including 2019 Australian Christian Book of the Year, The Fountain of Public Prosperity: Evangelical Christians in Australian History 1740–1914. He came to study revival seemingly by accident in the 1970s while researching the 1902 Mount Kembla mining disaster. Piggin stumbled upon a local newspaper story about an extraordinary religious event that also occurred in 1902 in the Illawarra region.

“It’s a bit of a shock to discover that the life that you’ve lived, even as a Christian, has been suboptimal, less than the reality which God has intended for us,” – Stuart Piggin.

“In all the mining communities, which dotted the coastline like beads on a string, there was this blessing and hundreds of people were brought to the Lord. I thought, this is amazing. What’s going on here?” He began finding revivals everywhere, particularly in the 19th century and in Methodist circles.

Miners State Library of South Australia / Wikimedia Commons

Wanting to understand the theological underpinnings, Stuart turned to Jonathan Edwards, the American theologian said to be the church’s finest theologian on revival. Edwards described revival as “waking up to reality”.

“Edwards thought that reality was greater than truth. Reality is the world as it is made and perceived by God,” Piggin explains.

Edwards noted there is a sudden realisation that one’s own perspective is not God’s perspective. “That’s why revivals are very dramatic and often involve emotion. It’s a bit of a shock to discover that the life that you’ve lived, even as a Christian, has been suboptimal, less than the reality which God has intended for us,” says Piggin.

The implication is that the church, believers, were asleep. Tired. At times, exhausted.

Pastor Jemima Varughese remarks that “revival is about bringing what was dead back to life.” Varughese is a voracious student of the history of revival, which continually stirs her own passion for a move of God. “I look at all that and pray, ‘God, do it again. Do it in me. Do it in our cities, do it in the church today,” she says.

Varughese is passionate about Christians, especially children, learning the history of revivals. Kingdomcity have an online school for students (K–12) located anywhere around the world and have included a curriculum on revivalists.

The characteristics of revival

“Revival is a concerted assault on the powers of darkness. So, there is spiritual dimension,” says Piggin.

As people experience God’s presence during a revival, there is a shift of focus away from the self and onto God; moving a person from self-reliance to God-reliance. This sense that “with God, all things are possible” (Mark 19:26) invigorates people, revitalising churches and communities.

One of the most important contemporary Australian revivals was among Aboriginal people, beginning in Elcho Island in 1979 with Rev. Dr Djiniyini Gondarra. “Aboriginal revivals were critical because they empowered First Nations people for the hard work of claiming their identity, which enabled them to survive and thrive in this world,” says Piggin. He suggests that there is a strong link between the 1979 revival and First Nations’ land rights developments. Another great revival in Pinnacle Pocket released scores of Aboriginal pastors into ministry.

“Across Canada, New Zealand, the UK and Australia, there are small fires all over the place. Like a bushfire, revival takes off when the environment is right.” – Mark Sayers

Pastor Mark Sayers notes that revivals have always been contagious, and now with digital media, there’s a virality like never before. This can be seen in the outpourings at other universities and colleges in the weeks following the Asbury Revival.

Sayers began studying revivals after a period of difficulty and personal transformation in his spiritual life. He has observed that “across Canada, New Zealand, the UK and Australia, there are small fires all over the place. Like a bushfire, revival takes off when the environment is right.”

Revival often comes in times of crises, Sayers adds, saying, “We are facing multiple crises right now. Emerging generations are losing their belief in some of the promises of worldly culture.”

This link between revivals and crises may be one reason why revivals are not long-lasting. Piggin suggests that revivals don’t last because “through revivals, God equips us for a purpose and to get on with it. Once we’re refreshed, we can start again.”

How do we test if a revival is a genuine work of the Holy Spirit?

Even Jonathan Edwards received opposition when he talked about revival in his many studies on the Great Awakening. For Edwards, a work of the Spirit is more than emotion or a change of mind – it changes the affections; our strongest inclinations. It changes what we love most and our will. He had a sixfold test to distinguish a genuine work of the Spirit of God:

1. It makes you love God more; God for himself – his glory, power majesty and love – rather than what he can do for you.

2. It makes you love Jesus more and recognise what he did on the cross for you.

3. It makes you love the Bible more.

4. It makes you love Christian doctrine more.

5. It makes you love other people more.

6. It makes you love the devil less and sin less.

This increase in love always spills out into the community. In the 1902 Illawarra revival there were 2735 conversions throughout the coalmining villages – 15 per cent of the region’s population. There were reports of miners doing more earnest work, repaying debts and consuming less alcohol.

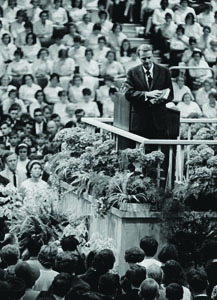

“I read in the local press that the pit ponies [mining horses] had stopped working – they didn’t understand the commands of the miners because they had stopped swearing,” notes Piggin. The great revivals have always resulted in a decline in national crime and immorality. The same is true of the Billy Graham Crusades in Australia in 1959.

A work of the Spirit is more than emotion or a change of mind … It changes what we love most and our will, says Piggin.

“You look at The Great Awakening, that overflowed into social reform – everything from slavery, to the creation of the RSPCA. Revival increases people’s love for Jesus, which then flows out into the world,” says Sayers.

What precedes revivals?

There is no formula, but Piggin has observed three things that have always preceded revival:

1. Unprecedented prayer for revival;

2. Unusual unity among Christians;

3. Heightened faith and expectation for a move of God.

“Whenever you study a great move of God, you’ll find that there was a group of people who were praying beforehand,” says Varughese. She notes that Evan Roberts (Welsh Revival, 1904-1905) had prayed for revival since he was 13 years old. “I haven’t heard of a revival where God’s just turned up and there’s been no hunger. There’s got to be a hunger. There’s got to be prayer.”

Piggin notes that Methodists were particularly expectant for revival. “They expected revival and that’s why they prayed for it. Methodists tended not to hold evangelistic meetings until the expectation was high, till they were confident that God was in this,” says Piggin. Pentecostals, as the heirs of the Methodists, have inherited the godly habit of expecting revival.

Billy Graham preaching Erling Mandelmann / photo©ErlingMandelmann.ch

Different flavours of revival

Some revivals are characterised by amazingly gifted preachers like George Whitefield, the Anglican preacher, whose dramatic preaching style sparked the American Great Awakening movement. American revivalist preacher Jonathan Edwards would give you 12 reasons why you shouldn’t want to go to hell. By reason number five, you were totally convinced.

Billy Graham, with his passionate, energetic preaching style that led to his nickname ‘God’s Machine Gun’, led thousands towards Christ.

In the Welsh revival, however, there was sometimes no preaching. Evan Roberts would encourage his female singers to sing, and he would hardly say anything. Music and worship have a lot to do with revival, notes Piggin.

“With Asbury, [God] didn’t use production, he didn’t use lights, he didn’t use screens to attract that generation of young people, he used repentance and prayer. It’s just another side of him,” Varughese says.

In the Azusa Street Revival, which started in Los Angeles in 1906, God used African-American pastor William Seymour while racial segregation thrived in the US. The effect was to renew and unite diverse people. Eyewitness Frank Bartleman noted that “the ‘colour line’ was washed away in the blood.”

Where to from here?

In 1889, Melburnian minister John MacNeil started a prayer meeting with four other ministers on Saturday afternoons. “The Band”, as they called themselves, were joined by ministers from other denominations praying for “the big revival”. Their longing for it deepened in their hearts. They determined to pray without ceasing until they saw it, at times spending whole nights in prayer. Later that year, MacNeil invited every minister in Victoria to a day of prayer – 700 came.

By 1902, 200 churches (80 per cent of those in the region) came together to pray and prepare for a great evangelistic gathering for which they had petitioned. MacNeil had passed on to heaven but “The Band” and 30 home prayer meetings, started by a Mrs Warren, grew to 2100 meetings.

By the time American evangelist R.A. Torrey arrived in Melbourne in 1902, thousands were eagerly awaiting an outpouring of the Holy Spirit. At the height of that revival, 250,000 people (of 1.2 million in the region) attended across many simultaneous meetings in one night.

Revival “begins in a hungry few. If you’re a minister, gather the hungry people in your church. All you need to do is open a regular space for prayer and invite people to come,” encourages Sayers.

“We need to work together; we can’t stand alone. We all have different flavours and that’s good because people are different.” – Jemima Varughese.

Sayers suggests that now is the time to reach out across the denominational divides in your local community. “Prayer is something we can all agree on. Gathering to pray with people in your area, that’s what our church is doing.”

Varughese concurs, “The church down the road is not competition. There is so much need in our communities and it’s too big for one church to do alone. We need to work together; we can’t stand alone. We all have different flavours and that’s good because people are different.”

She continues, “We’re coming into a time in the world where if we don’t have prayer as part of our life, or a core part of our church, we probably won’t survive. In my church, we have really ramped up our prayer – more prayer groups, prayer teams praying around the clock.”

Piggin has often wondered why Edwards used the word “surprising” in his book The Surprising Work of God, when there had been revivals before in his father’s church and his grandfather’s church. “I was interested to find that Edwards never used that word to describe revival, it was put in by his editors,” says Piggin.

“We’ll always find [revivals] remarkable. We’ll always wonder at them, praise God. Rather than be surprised by revivals, we should be surprised by their absence,” he asserts.

“They are for the refreshment of the church, which the church desperately needs. And for the relief of problems in the nation, which the nation desperately needs. It’s a fearful time. We should be surprised if we don’t enjoy and experience a revival,” says Piggin.

Revivals are not taught, they’re caught. When you learn about a revival, it can spark in you the same desire for a move of the Spirit. That’s why it’s important to talk about them, read about them and pray for them so that perhaps we might come together and cry out, “God do it again. Do it in our city. Do it in me.”

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?