Harriet Tubman was working in a laundry and as a nurse in South Carolina before the Union Army asked her to lead a spy mission during the American Civil War.

The illiterate African-American former slave was handpicked by the North’s Colonel James Montgomery – an abolitionist – to head a team of scouts gathering intelligence for a raid on Confederate-held plantations. He wanted to rescue slaves, as well as recruit them to the Union cause, while destroying the properties they had been forced to work on.

On June 1, 1863, Tubman became the first woman to lead an armed expedition in the Civil War.

During the night, she helped guide two boats down the mine-filled Combahee River – from memory, not maps – to places which Tubman designated as escape points for enslaved African Americans.

With bullets flying and women running with babies in their arms, Tubman and the Union forces managed to liberate more than 700 slaves in one night.

In a news story in the Wisconsin State Journal, a reporter referred to emancipator Tubman as “She Moses” – without identifying her.

But this female freedom fighter was already widely known, having been dubbed “Moses” by abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison.

For a decade before the Civil War, Harriet Tubman had been a skilled architect of dangerous escapes for slaves in the American South. And like the man chosen by God centuries earlier to lead his people out of bondage in Egypt, Tubman credited her strength, abilities and survival to the will of God.

Harriet is back

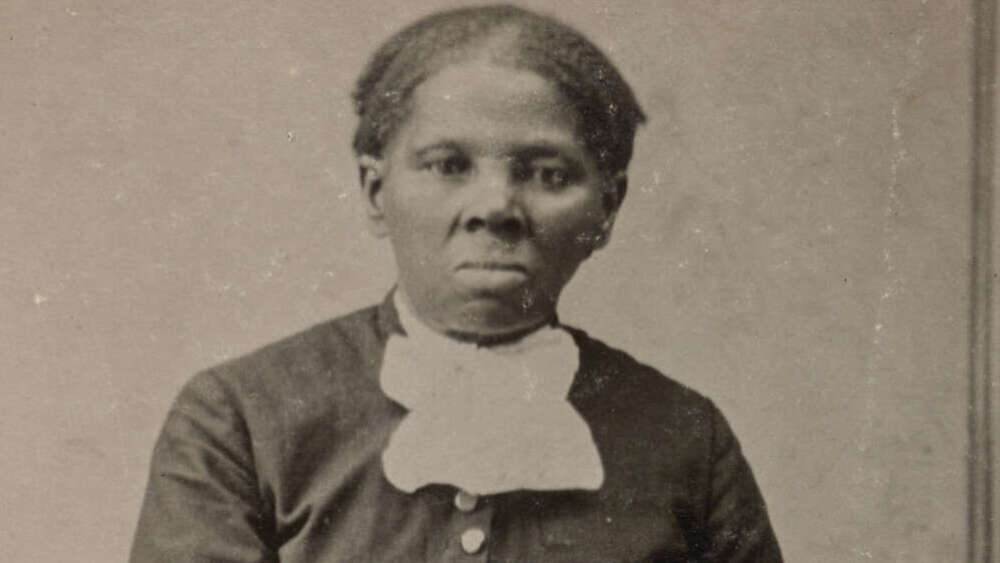

One of the first things US President Joe Biden did when he took the top job in January was to resurrect a promise made during Barack Obama’s second term. Harriet Tubman had been named to replace US President Andrew Jackson – a slave owner – on the American $20 bill.

Tubman would become the first woman to have her face on US paper currency and the notes were intended to start circulating in 2020, the 100th anniversary year of women being afforded the right to vote in the US.

However, the change did not happen when President Trump branded it “pure political correctness”. Fast forward to Biden’s administration and it has confirmed the Treasury Department is back on the Tubman task.

“I never met any person of any colour who had more confidence in the voice of God.”

“It is important that our … money reflects the history and diversity of our country, and Harriet Tubman’s image gracing the new $US20 note would certainly reflect that,” said Biden’s Press Secretary Jen Psaki last week.

“We are exploring ways to speed up that effort.”

‘God, you’ve got to see me through’

Tubman’s efforts to help slaves achieve the freedom she found have become the sort of legend that real-life can sometimes deliver. From the actual number of people she rescued, to claims there was a $40,000 bounty on her head (by comparison, John Wilkes Booth had a $50,000 bounty after he shot Abraham Lincoln), Tubman can almost seem to be a superhero of imprecise proportions.

But one of the things anchoring the Tubman tale is her grip on God. “I always told God,” she said, “‘I’m going to hold steady on you, and you’ve got to see me through.'”

As Christianity Today describes, “Tubman’s friends and fellow abolitionists claimed that the source of her strength came from her faith in God as deliverer and protector of the weak.”

Although some of the details are debatable, Tubman’s life was evidently shaped by trust in the one to whom she “always prayed”, who could “make me strong and able to fight.”

Tubman was known for being guided by visions which she believed came from God. “I never met any person of any colour who had more confidence in the voice of God,” said abolitionist Thomas Garrett about the middle of nine children born to enslaved parents in Maryland (somewhere between 1820 and 1825).

Born Araminta “Minty” Ross, Tubman and was hired out by the family who “owned” her. She would drive oxen, plough fields, haul logs and care for children. During the 1930s, Minty was hit in the head when a slave owner threw a weight at her for refusing to help restrain a runaway slave. Seizures, severe headaches and sleep problems plagued her for the rest of her life. But she also began to experience intense dreams and visions, which she attributed to God.

She married John Tubman, a free Black man, around 1844, and also changed her full name (Harriet was her mother’s name). Without her husband, Tubman escaped from her life of slavery in 1849 when she seized the opportunity created by her master’s death. Before a new owner arrived, she “turned her face toward the north, and fixing her eyes on the guiding star, and committing her way unto the Lord, she started … upon her long, lonely journey” (as biographer and supporter Sarah Bradford wrote in 1886’s Harriet Tubman: The Moses of Her People).

Fact and fiction of freedom

Bradford’s account of Tubman’s escape – which she claimed was based on Tubman’s own words – is an example of the mystery and mystique around the Black Moses of the 19th Century.

Other historians claim Tubman fled slavery with the definite help of those involved with the ‘Underground Railroad’, a network of safe houses, secret routes and abolitionists into the free North.

“She normally rescued people in the winter, when the long dark nights provided cover, and she often adopted some type of disguise.”

Up until 1860, Tubman led many rescue missions out of Maryland as a chief conductor of the Underground Railroad. Her first mission was in 1850, bringing out her niece Kessiah, her husband and their children.

Bradford estimated Tubman completed 19 separate missions and liberated about 300 people. Recent biographer Kate Clifford Larson says the numbers are closer to 10-12 missions, freeing between 60 and 80 people – based on what Tubman herself shared in 1858 and 1859.

Such conjecture can become a worthless distraction, though, if it steers us away from marvelling at what Tubman did.

‘I never lost a passenger’

Regardless of exactly how many times and for how many people, this God-powered former slave frequently put her life in peril. The Fugitive Slave Act (1850) imposed severe punishments on any person who assisted a slave’s escape, but Tubman proved a considered and cunning escape artist.

“She normally rescued people in the winter, when the long dark nights provided cover, and she often adopted some type of disguise,” described history professor Robert Gudmestad on The Conversation.

“She avoided actually going into plantations,” continues Christianity Today. “She waited for escaping slaves (to whom she had sent messages) to meet her eight or ten miles away. Slaves would leave plantations on Saturday nights so they wouldn’t be missed until Monday morning, after the Sabbath. It would thus often be late on Monday afternoon before their owners would discover them missing. Only then did they post their reward signs, which men hired by Tubman would take down.”

“When I found I had crossed that line, I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person.”

“Because her rescue missions were fraught with danger, Tubman demanded strict obedience from her fugitives. A slave who returned to his master would likely be forced to reveal information that would compromise her mission. If a slave wanted to quit in the midst of a rescue, Tubman would hold a revolver to his head and ask him to reconsider.” Reportedly, she never pulled the trigger during any rescue.

As Time put it, “she was an indomitable leader who had her God and her gun as her only weapons.” Most tributes to Tubman don’t linger on the second part of that arsenal, given the times and what she was up against. Instead, the steady refrain about her Moses-like activities contains the air of amazement and respect which Tubman herself understated when addressing a suffrage convention in 1896: “I was the conductor of the Underground Railroad for eight years and I can say what most conductors can’t say – I never ran my train off the track and I never lost a passenger.”

Tubman died one year before World War One, having also been involved with the suffrage movement.

Before the Black Moses who devoted so much of her life to other people’s freedom is commemorated on US currency, her immediate reflection upon reaching the North after fleeing the South is a fitting memorial to a woman empowered by God’s unchained hope.

“When I found I had crossed that line, I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person,” Tubman said.

“There was such a glory over everything; the sun came like gold through trees, and over the fields, and I felt like I was in heaven.”