Why do people burn crosses?

When a group of neo-Nazis got together in the Grampians, a popular Victorian tourist destination, over the Australia Day weekend, images of the masked men standing in front of a burning cross made national headlines.

Thirty-eight members of the far-right National Socialist Network participated in the ritual, described as being associated with the Ku Klux Klan. They chanted “white power” and other Nazi slogans.

But how did the cross – the principal symbol of Christianity, and a sign of love and sacrifice – become tied up with the KKK as a symbol of hatred?

The influence of the Scots

The Ku Klux Klan was founded in the 1860s as a club for Confederate veterans. It was established as a vigilante group against the progress of Reconstruction – the period after the American Civil War when attempts were made to redress the inequalities of slavery and its legacy, and readmit the Union of 11 states that had seceded. The first wave of the Klan had members from all parts of US Southern white society and used violent intimidation to prevent Black people (or white people seen as supporting them) from voting or holding political office.

A group of Ku Klux Klan members burning a cross in Knoxville, Tennessee. September 4, 1948. US Library of Congress

“The first KKK was a terrorist organisation in the literal meaning of the word ‘terror’,” said Linda Gordon, Professor of History at New York University and author of The Second Coming of the Ku Klux Klan.

Gordon told Eternity that it was unlikely that the first group ever burned crosses.

“The original KKK was not particularly religious. They didn’t make a big deal of religion in their activities. They would, almost all of them, claim Christian belief, of course, but this wasn’t a religious group in itself.”

The first Klan was, however, a secret society, and some historians believe it was inspired by Scottish history.

Some 14th Century Scottish clans would set ablaze crosses on hillsides, as symbols of defiance against military rivals or to rally troops when a battle was imminent. But the first wave of the Ku Klux Klan didn’t engage in the practice.

The first wave of the KKK died out when it became clear that ‘Jim Crow’ laws in the US – “state and local statutes that legalised racial segregation” – would cement white supremacy.

The KKK no longer needed to operate in secret. In fact, it didn’t need to use vigilantism at all. The law of the land did the job for them well enough.

The influence of Hollywood

In 1905, Thomas Dixon wrote The Clansman, a romanticised account of the Klan which included its supposed Scottish ancestry, and depicted a fictional Klan cross-burning. Dixon called cross burning the “ancient symbol of an unconquered race of men”.

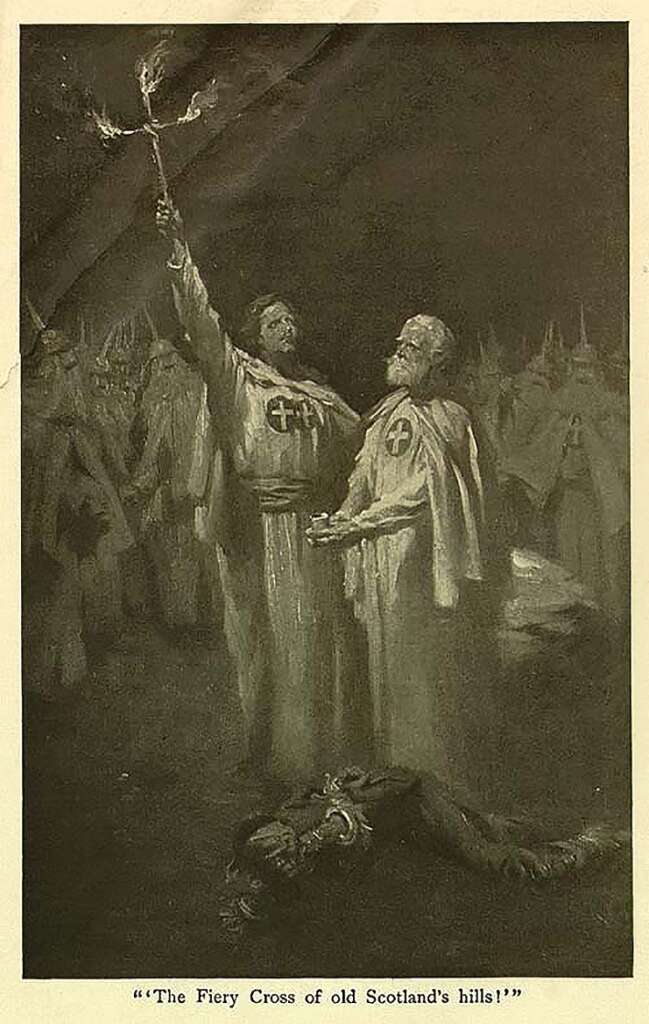

An image from Thomas Dixon’s 1905 book, The Clansmen, depicts cross burning at the scene of a lynching.

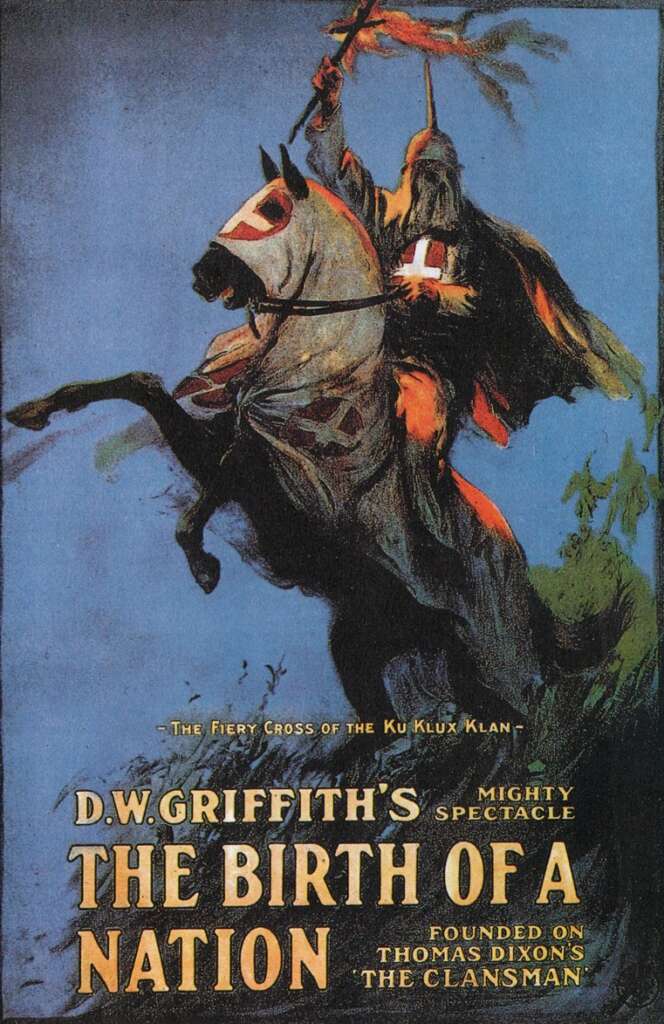

Theatrical poster for The Birth of a Nation.

The image was reconstructed in The Birth of a Nation, a 1915 film by director D.W. Griffiths, based on Dixon’s book.

In 1915, Methodist preacher William J Simmons and about 15 other men climbed Stone Mountain in Georgia, and put a match to a pineboard cross. As the cross went up in flames, they announced the revival of the Ku Klux Klan.

That was the second recorded cross-burning in the United States. The first was recorded on the same mountain in Georgia just a month before the KKK revival, when a mob celebrated the lynching of Leo Frank – a Jewish man accused of murdering a 13-year-old girl – by burning a “gigantic cross” on Stone Mountain. As Wyn Wade wrote in The Fiery Cross: The Ku Klux Klan in America, it was “visible throughout” Atlanta.

A Christian symbol for a religious KKK

The second wave of the KKK – begun by Simmons on that Georgian mountainside – restricted membership to white Christians. Members wore white robes to symbolise “purity” and burned crosses to signify “the light of Christ”.

“The second version of the Klan was really the product of evangelical Christianity,” Gordon told Eternity. “It was very religiously-oriented.”

The second wave of the KKK was primarily a non-violent movement, said Linda. “They were involved in electoral campaigning,” she said, and targeted not just African Americans, but immigrants, Catholics and Jews. Despite its non-violent claims, many instances of Klan violence have been recorded, including murder, floggings, and tar and feathering.

“They could be very provocative,” said Gordon, recounting one instance when the Klan burned crosses around the perimeter of a Catholic university, or plastered leaflets on synagogues. Crosses were burned as intimidation tactics and threat.

“But the cross burning was often not a direct threat against anyone in particular. You’d often see these burning crosses at monster rallies that the KKK held. In the 1920s, the KKK was not a secret organisation. It was entirely public. Burning crosses was like a form of fireworks.”

At its peak in the 1920s, the KKK boasted close to five million members, and was extremely popular in the North of the United States.

“After a time, they started using light bulbs on the crosses instead. It reduced the threatening nature of it. It was just a symbol.”

“The burning cross in the KKK did not have the same meaning at various moments in its history.”

The second wave of the KKK was depleted by the Great Depression in the 1930s, and all but petered out by the end of WWII.

The third wave of the KKK

The third wave of the KKK arrived in the Deep South of the US during the 1960s. The KKK burned crosses on the lawns of those involved in the Civil Rights movement, and in Alabama and Mississippi murdered African Americans, attacked the ‘Freedom Riders‘ and bombed a primarily-black church in Birmingham, killing four young girls.

Wade writes that the Klan constitution (called The Kloran) outlined that the “fiery cross” was the “emblem of that sincere, unselfish devotedness of all klansmen to the sacred purpose and principles we have espoused”.

Freedom of speech and cross burning

In 2002, the US Supreme Court struck down a Virginia state law that banned cross-burning, because of the law’s unconstitutional presumption that all cross-burning is intended to intimidate.

Barry Black set fire to a cross on a private farm in Carroll County, with permission from the owner of the farm to use the area for a KKK rally and to ignite a cross as part of the ceremony. He was charged under Virginian cross-burning laws.

Black described cross burning as “a very sacred ritual“.

“We don’t light [the cross] to desecrate it,” he told The Roanoke Times in 1999. “We light it to show that Christ is still alive.” The burning symbolises the “burning away of evil”, according to Black

In the court’s decision, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor said in Virginia v Black, “To this day, regardless of whether the message is a political one or whether the message is also meant to intimidate, the burning of a cross is a ‘symbol of hate’. And while cross burning sometimes carries no intimidating message, at other times the intimidating message is the only message conveyed.”

“While a burning cross does not inevitably convey a message of intimidation, often the cross burner intends that the recipients of the message fear for their lives. And when a cross burning is used to intimidate, few if any messages are more powerful,” O’Connor wrote.

However, she wrote, “As the history of cross burning indicates, a burning cross is not always intended to intimidate. Rather, sometimes the cross burning is a statement of ideology, a symbol of group solidarity. It is a ritual used at Klan gatherings, and it is used to represent the Klan itself. Thus, ‘burning a cross at a political rally would almost certainly be protected expression’ [referencing a previous case].”

The modern cross-burning

The cross-burning in the Grampians last month in Australia sparked some to call for the National Socialist Movement, and groups like it, to be added to official terrorist lists.

https://twitter.com/KKeneally/status/1354883544712024065?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1354883544712024065%7Ctwgr%5E%7Ctwcon%5Es1_&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.sbs.com.au%2Fnews%2Fhow-the-modern-face-of-hitler-began-rearing-its-head-as-australia-marked-holocaust-remembrance-day

These days, says Professor Gordon, white nationalists are more likely to announce their racism “by hanging a noose”.

“It’s the symbol of lynching. When the mob entered the Capitol building on January 6, some of the protestors erected a noose as a threat to black people and an assertion of white supremacy,” she said.

According to Slate, nearly 1700 instances of cross-burning have been recorded in the United States since the 1980s, many of them in the front yards of African-American families “although, in all fairness, the majority have been carried out by lone racist yahoos, rather than by organised Klan groups.”

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?