A real danger to religious freedom

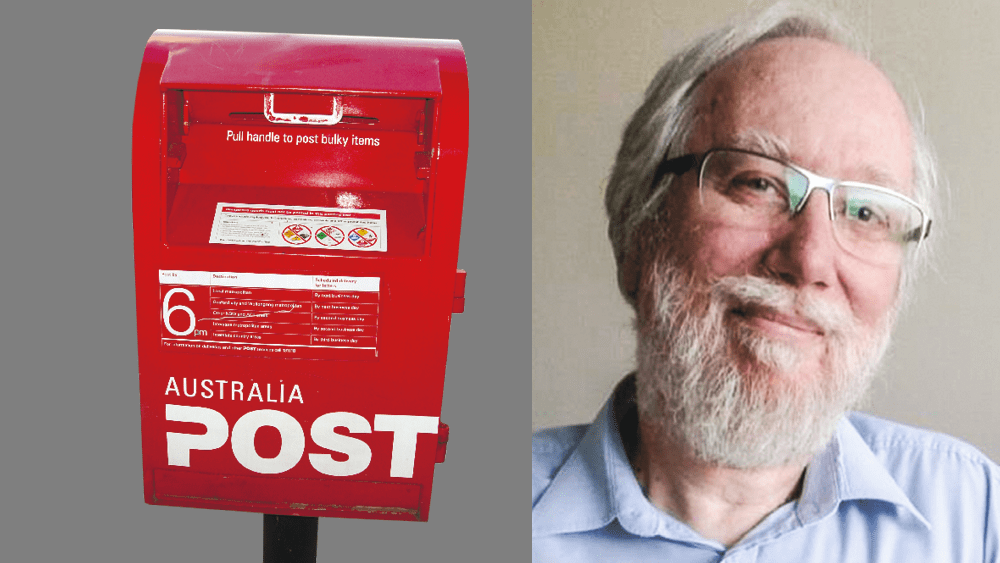

Neil Foster says key issues need to be addressed

There are many good reasons to retain the classical definition of marriage as the voluntary union for life of one man and one woman, to the exclusion of all others, as part of the law of Australia. I have written about some of those reasons elsewhere. But here I would like to briefly outline the case for retaining the classical definition, and voting “No” to the current survey question, based on the negative implications for religious freedom in Australia that are likely to flow from any recognition of same-sex marriage (SSM).

Why is religious freedom important?

Why be concerned about religious freedom? And do we really have to worry about it in Australia – anyone can go to church or a synagogue or a mosque whenever they like, can’t they?

But protecting religious freedom is about more than going to church. Australia has signed up to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (the ICCPR), and article 18 provides for a fundamental human right of religious freedom. This is not just the right to have a private belief, but a person’s “freedom, either individually or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his [or her] religion or belief in worship, observance, practice and teaching.”

Section 116 of our Federal Constitution also forbids the Commonwealth Parliament from making a law “for prohibiting the free exercise of any religion” (although the scope of this provision is limited, not extending to state laws).

Religious freedom, then, is about more than the right to hold certain opinions internally; it is about a right to “free exercise” of religion, which will mean that a person will live out their religious beliefs in everyday life. Indeed, it is a fair criticism of someone who claims to be a believer that their life does not match their claimed religious beliefs. All of us are grateful when people with deep religious beliefs live out those beliefs in caring for the poor and marginalised, in generous giving to worthy causes, and in looking after people in their local communities. So we need to resist the occasional “reframing” of religious freedom in terms of “a right to worship”; it is much more than that.

What are the limits on religious freedom?

Yet, like every other “right”, the right to religious freedom is not absolute, and needs to be balanced with other rights. We don’t allow the sacrifice of humans on the top of pyramids. Under international law, article 18(3) of the ICCPR says that Australia can limit the free exercise of religion in a narrowly defined set of circumstances, including by passing a law that is “necessary to protect … the fundamental rights and freedoms of others.” Generally, the right to not be discriminated against on irrelevant grounds is regarded as one of those “fundamental” freedoms.

But the fact that some limits on religious freedom are justified, does not mean that all possible limits are right. The rights of believers to live in accordance with their deeply held convictions about what God requires of them, is an important feature of our democratic heritage. And it has to be said that there is no “human right” to be able to marry a same-sex partner (see my earlier comments here and the very recent affirmation of this in a Northern Ireland court.) At the moment in Australia there is almost no difference at all between the statutory rights and benefits available to same sex couples, and those available to those who are formally married.

What are the likely impacts of SSM on religious freedom?

How does this relate to SSM? Both as a matter of logic and experience, introduction of formal recognition of SSM leads to serious challenges to the rights of believers to live in accordance with their fundamental religious commitments. Indeed, because of the patchwork and unsatisfactory scope of religious freedom protections in Australia at the moment, the implications of this change have the potential to be even more serious in this country than in other Western countries that have made the change.

Many religious groups have clear doctrines that provide that an essential feature of marriage is that it be between a man and a woman, and that homosexual activity is contrary to divine purposes for humanity. That is certainly the mainstream position of the Christian church, and has been since the founding of Christianity. There are, then, a number of religious freedom issues presented for religious groups and individual believers by proposals to fundamentally transform a social institution in which religious beliefs have played a key part for millennia. As I indicated in a submission I made to a Parliamentary Committee considering the religious freedom protections provided by an Exposure Draft released by the Government, some of these issues are:

- whether religious celebrants will be required to solemnise SSMs;

- whether other celebrants, not formally associated with a religious group, will be so required;

- whether religious groups will be required to host same sex weddings on their premises;

- whether public servants who are employed in registry offices will be allowed to exercise their religious freedom to decline to solemnise such marriages;

- whether small business owners in the “wedding industries” (such as cake makers, florists, photographers, stationary designers, and wedding organisers) will be permitted to decline to use their artistic talents for the celebration of a relationship that God tells them is not in accordance with his purposes for humanity.

Some of those issues were dealt with in the Government draft, others were not. And the later Parliamentary inquiry did not even accept the minimal protections provided by the Government draft. These, however, are just the specific issues with the “ceremony” for SSM. There are number of broader issues that arise once SSM is authorised by the law of Australia to be the equivalent of classic marriage.

- Will there still be robust freedom of speech protection for believers to express their views, based on their deep religious convictions, that SSM is not a good idea?

- Will religious schools be able to continue to teach children who are sent to them by parents who want their child to have a religious education, what those views are? Or would such views be regarded as “hate speech”?

- Whether financial support currently offered to religious organisations that provide important services to the community will be conditioned on support for SSM?

- Will educational institutions operating on religious principles find their students unable to work in the wider culture unless they affirm the validity of SSM?

- Will employees be sacked for holding the “wrong” views on this issue?

These are not theoretical, academic, questions. There are clear examples of actual court decisions overseas imposing damages awards of a large amount on small business owners who politely declined to make their artistic talents available to celebrate a sexual relationship they see as sinful. There are documented examples of employees who have been disciplined, and students suspended, simply for expressing their belief in classic marriage. In Tasmania a Catholic bishop was sued for presenting Catholic teaching on the matter to Catholic school students.

I have to disagree, then, with the Attorney-General, who recently said that these matters can be resolved in Parliament after the decision is made whether or not to allow same sex relationships to be recognised as marriage. The impact of the change on religious freedom is an important reason, even if not the only one, why there should be no such change.

Neil Foster is an evangelical Christian, an Associate Professor in law, a father and a grandfather.