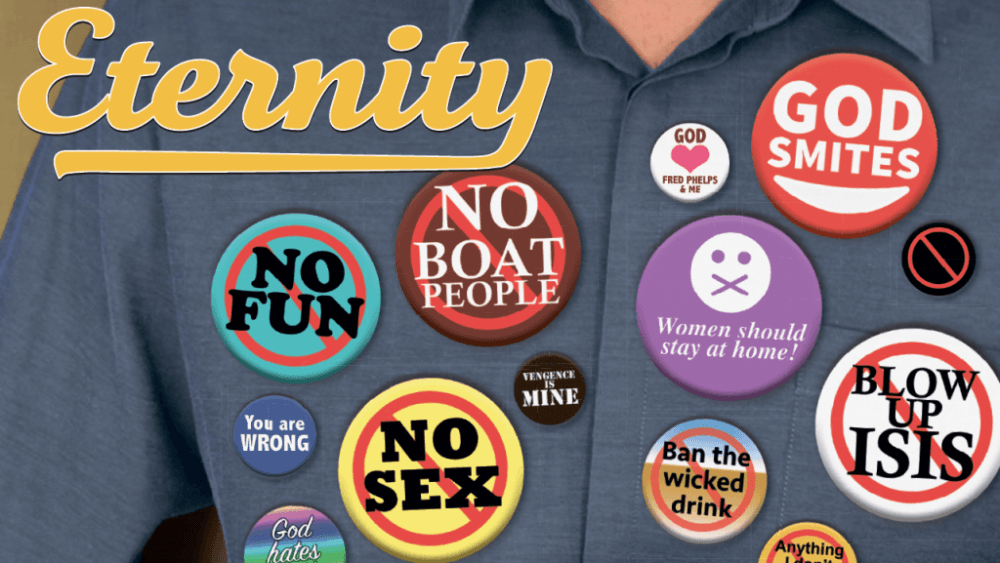

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been confronted with the sweeping criticism that Christians are all narrow-minded, judgmental and even hateful. I usually respond by politely conceding that this is indeed sadly true of some church folk, before I try and point people to the loving counterexample of Jesus Christ.

But after two decades of travelling the world serving alongside Christians across the denominations, I have recently begun to wonder, “Where on earth is this mass of horribly bigoted Christians?” Sure, I’ve come across a handful of Christian “haters” – more on the Christian airwaves than on the ground in churches – but they are so vanishingly small that I feel another theory is required to explain the widespread secularist impression that the church is hateful.

Perhaps it is the de-Christianised Western society and not the church that has lost touch with a culture of grace.

I want to offer such an explanation, without at all avoiding the fact that Christians sometimes don’t live up to their ideals, or denying that sometimes our secularist friends are more “Christian” in their behaviour than many church folk. In short, I wonder if the common accusation that Christians are narrow, judgmental and hateful is rooted in precisely the opposite reality from what many people imagine. Perhaps it is the de-Christianised Western society and not the church that has lost touch with a culture of grace.

Most Christians operate within a theology and culture of “grace”, where profound moral disagreement between people is never interpreted as an absence of love between them. For starters, at the root of Christian faith is confidence in God’s enduring love for us despite the depths of his holy disagreement with our sin.

Divine grace is the starting (and ending) point of all Christian theory and practice.

Moral disagreement and enduring love are central to both God and Christian theology.

But then there’s the fact that most believers find it possible to talk about their shared sinfulness without ever imagining they could not at the same time love one another, and indeed themselves. C.S. Lewis once pointed out that there is a perfectly natural example in our world of “loving the sinner while hating the sin”: it’s the way we treat ourselves, despite our failures.

So, when Christians are asked for their opinions on contentious moral issues, such as gay marriage, abortion and euthanasia, they don’t imagine that sharing their contrary opinions with gentleness and respect could be interpreted as hateful or judgmental. In a grace paradigm, that would never enter into it. Moral disagreement and enduring love are central to both God and Christian theology.

But our secularising society has been slowly losing its Christian vision of life. While many examples of the Christianisation of the West still remain – our commitment to charities, our love of humility, our insistence that every human being is inherently valuable – the culture of grace flowing from a theology of grace has not fared well.

Disagreement, especially moral disagreement, has come to imply hatred or, at the very least, disrespect.

Nowadays, disagreement, especially moral disagreement, has come to imply hatred or, at the very least, disrespect. Gone from our culture is the ethical imagination which grace inspires: allowing someone to critique and love at the same time, and, just as importantly, the ability to be critiqued and still know you are loved at the same time.

All that is left in a graceless culture is an impoverished moralism, which demands agreement as the true sign of compassion, and which in turn inspires contempt for those who disagree. Of course, when churches lose their gospel of grace, they too can become institutions of mere morality – dividing human beings into the “good” and the “bad”, instead of showering love on all regardless of performance. But this is not what Christianity is in its default mode. British intellectual Francis Spufford puts it provocatively in his book Apologetic: How, Despite Everything, Christianity Can Make Surprising Emotional Sense:

The myth of the hateful Christian Ryan McGuire

“So of all things, Christianity isn’t supposed to be about gathering up the good people (shiny! happy! squeaky clean!) and excluding the bad people (frightening! alien! repulsive!) for the very simple reason that there aren’t any good people. Not that can be securely designated as such. It can’t be about circling the wagons of virtue out in the suburbs and keeping the unruly inner city at bay. This, I realise, goes flat contrary to the present predominant image of it as something existing in prissy, fastidious little enclaves, far from life’s messier zones and inclined to get all ‘judgmental’ about them. Again, of course, there are Christians like that. … The religion certainly can slip into being a club or a cosy affinity group or a wall against the world. But it isn’t supposed to be. What it’s supposed to be is a league of the guilty. Not all guilty of the same things, or in the same way, or to the same degree, but enough for us to recognise each other.”

In a grace culture, disagreeing and loving at the same time is routine. It’s second nature. The problem is: Christians can no longer assume that this distinctly Christian logic is shared, or even discernible, in the public square. As Australia secularises, perhaps there will be less and less of a tradition of grace. Ethical disagreement may increasingly be equated with judgment and bigotry. Christians need to think through the implications of this for how we communicate in public.

In short, maybe it is the graceless judgmentalism of secularist thinking that provides the internal logic for the assumption that the moral viewpoints of Christianity are hateful. Perhaps, in other words, when secularists accuse Christians of being narrow and bigoted, they are really looking into the mirror of secularism’s own tragic loss of grace.

Pray

Some prayer points to help

Pray that Christians would always speak with grace when explaining their beliefs to others.