A few years ago, the word ‘intersectional’ went from being an academic term to a culture wars weapon.

Coined in 1989 by Black feminist scholar Kimberle Crenshaw, the term had been a useful (though not uncontroversial) one for discussions about the many facets that make up an individual’s identity (including but not limited to race), and how these overlapping parts can impact someone in advantageous and disadvantageous ways.

But when progressives began to use it in mainstream forums, intersectionality’s definition became – in the words of writer Kory Stamper – “a bit flabby”. Intersectionality soon became a buzzword, a cliche and a hashtag, much to Crenshaw’s dismay, who said, “It’s like a very bad game of telephone.”

Conservative media pundits pounced on the diluted version of the word, using it with derision. Anyone concerned with intersectionality, they implied, wanted to force everyone to compete in a “victim olympics” they had rigged to win.

“The rigid social classes of the 1800s have been replaced with an equally rigid system of ‘intersectionality’, whereby a person’s power and privilege are determined by the amount of melanin in their skin,” warned Karen Lehrman Bloch in Intersectionality: The New Caste System.

Conservative onlookers – ordinary people who most likely were unaware of the term’s origin – were told to fear intersectionality at the same time they learned of its existence. They likewise adopted the word as a label, insult and general dismissal of progressive values.

So it was that a useful academic term was rendered a progressive cliche, then a culture wars weapon, in just a few short years.

In recent years, the word ‘woke’ has followed a similar trajectory.

Way back in 2017, the Oxford Dictionary expanded woke’s definition to include the adjectival meaning: “alert to injustice in society, especially racism”. Yet now the word is used by conservatives as a single-word denigration of all progressive values.

“The Woketopians will settle for [Joe] Biden… ” said US Congressional Representative Matt Gaetz in his Republican Convention speech last year.

UK Prince Harry and his wife Meghan Markle were recently dubbed the “oppressive King and Queen of Woke” in the The Sun newspaper.

Two weeks ago, US General Mark Milley – the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff – found himself needing to defend the US military from Republican claims that it has gone “woke” as a result of excessive diversity training.

Even Christian leaders have begin to use the word derisively.

“‘Woke’ Christian leaders and pastors today are jumping on the ‘hype train’ of what culture is currently applauding,” warned megachurch pastor Ed Young.

So where did the word woke come from and how did its meaning stray so far from that 2017 dictionary definition?

Furthermore, can a Christian use the word without drawing on the kind of dehumanising stereotypes that characterise culture wars? And should they?

Woke’s Black American history

Many of those who wield the word woke may not know about its contemporary usage in Black American history.

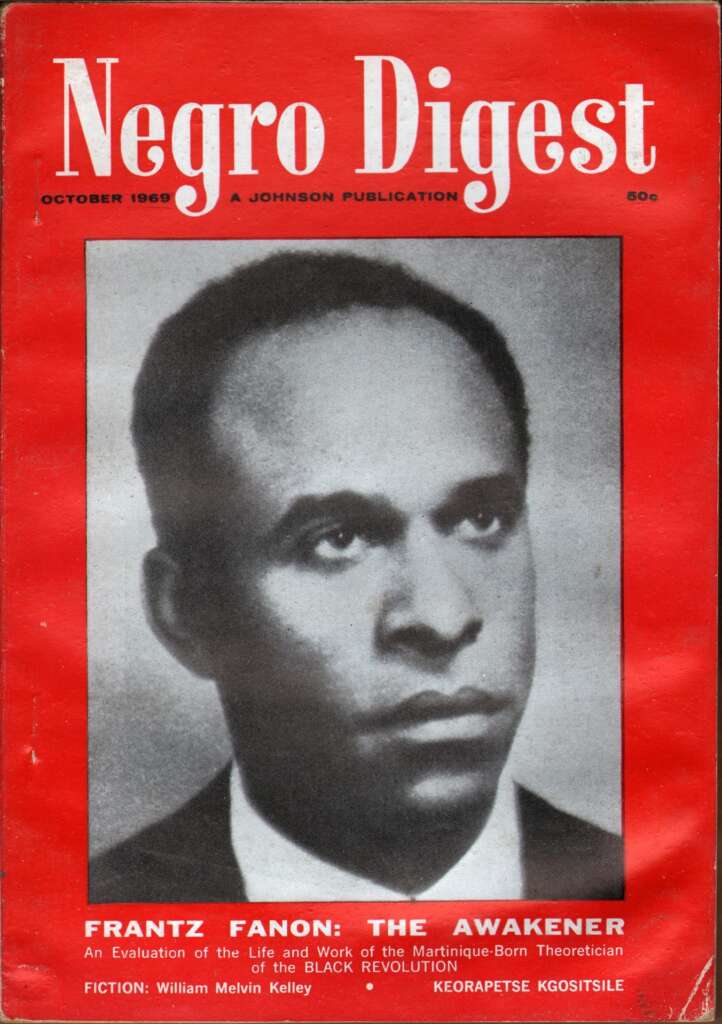

Its first recorded use was in an article about labor unions, appearing in an article by J. Saunders Redding, published in the first volume of Negro Digest in 1942. Redding was an African American author and educator who served as the first Black faculty member in the Ivy League.

” … a Negro United Mine Workers official in West Virginia told me in 1940: ‘Let me tell you, buddy, waking up is a damn sight harder than going to sleep, but we’ll stay woke up longer,'” Redding wrote.

In 1962, the New York Times published an article entitled: ‘If You’re Woke You Dig It; No mickey mouse can be expected to follow today’s Negro idiom without a hip assist. If You’re Woke You Dig It’. Then, in 2008, popular Black artist Erykah Badu’s song ‘Master Teacher‘ featured the lyric “I stay woke”. Badu later took woke to Twitter in 2012 when she encouraged fellow musicians, Pussy Riot, to also “stay woke” via tweet.

“Before 2014, the call to ‘stay woke’ was, for many people, unheard of,” explains Vox reporter Aja Romano.

Negro Digest Magazine’s first volume contained an article by J. Saunders Redding, using the word ‘woke’. Image: Biblio.com

“The idea behind it was common within Black communities at that point — the notion that staying ‘woke’ and alert to the deceptions of other people was a basic survival tactic. But in 2014, following the police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, ‘stay woke’ suddenly became the cautionary watchword of Black Lives Matter activists on the streets, used in a chilling and specific context: keeping watch for police brutality and unjust police tactics.”

Like intersectionality, woke began as a Black word that was helpful for talking about the experience of racism. Again, woke was corrupted by white progressives who used it to virtue signal. And just as was the case with intersectionality, woke was eventually co-opted by white conservatives who now use it as pejorative term to mock white virtue-signalling, and perhaps also the Black expressions of racism which progressives profess to support.

“Like many terms that have become popular and have broad purchase in African-American communities, it has been appropriated by people who consider themselves allies,” deandre a. miles-hercules succinctly explained in this ColorLines article. miles-hercules is a graduate student of California University’s sociocultural linguistics program.

“Conservatives then took it and weaponised it as a way to demonise people who were interested in social justice, equity and freedom,” miles-hercules says, before acknowledging that reclaiming a Black word once it has been co-opted is “tricky”.

“But Black people are hip to the game and are used to things that come out of our language and culture being weaponised against us.”

One question that has surfaced is whether woke’s re-appropriation has rendered it an entirely racially-neutral term – or not.

In essence, is a white person who uses the term to serve their own purposes doing something that is not only unhelpful, but also racist?

Meredith D. Clark, an assistant professor in the Department of Media Studies at University of Virginia told ColorLines that she believes using the word can be a form of anti-Blackness.

“It is a quick way to signal to others that whatever those people over there are saying is not real, not substantial, this is something that’s easily dismissed, you shouldn’t pay attention to it,” said Clark. “And that is the same sort of treatment that has been reinforced over and over again through anti-Black policies and social practices used to try to cement our position at the bottom of society.”

But, Clark said there is no need for Black people to attempt to reclaim the word, likening it to a translation situation where an English speaker gives a French or Arabic word a new meaning that native speakers need not accept.

“There’s nothing for us to take back from them, it’s up to them to figure out what it is that they don’t want named and why [they] are willing to co-opt our term in order to keep it from being named,” Clark said.

The history of the concept woke

Woke’s history as a concept – rather than a specific word – proves a useful study for non-Black Christians who want to respect Black people’s claim to the word’s historical roots and avoid cultural reappropriation, yet also want to embrace the insights it offers.

As the past tense of the verb “to wake”, the concept of being woke describes the process of one becoming alert and conscious after a period of sleep. It is used both literally and metaphorically. “Staying woke” is therefore, at its essence, about remaining awake.

Keen Bible readers will of course recognise this is a concept referenced in scripture, where there are exhortations to believers to remain spiritually awake (here’s a link to a casual ONE HUNDRED of them).

Yet woke weaponisers will rightly argue that the Bible’s call to stay spiritually woke encompasses more than simply being alert to earthly injustice.

But do Christians need to choose between staying alert to earthly injustice and being spiritually awake, or can they do both?

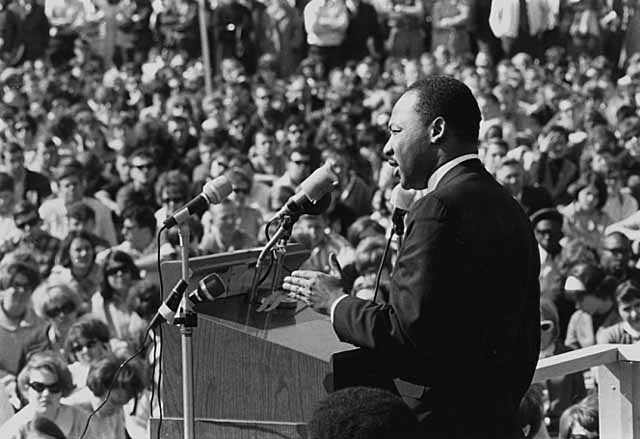

Martin Luther King, Jr., speaking against the Vietnam War, St. Paul Campus, University of Minnesota. Image: Minnesota Historical Society via Wikimedia

Civil rights leader and Black pastor Martin Luther King Jr clearly did not think the two aspirations were in opposition but rather entwined, judging by his discussion of the subject in a 1965 commencement address at Oberlin College, Ohio – Remaining Awake Through a Great Revolution.

King began his speech with a reference to Washington Irving’s story of Rip Van Winkle.

“While he was peacefully snoring up on the mountain, a great revolution was taking place in the world – indeed, a revolution which would, at points, change the course of history. And Rip Van Winkle knew nothing about it; he was asleep,” King told his audience.

“There are all too many people who, in some great period of social change, fail to achieve the new mental outlooks that the new situation demands. There is nothing more tragic than to sleep through a revolution.”

King went on: ” … a great revolution is taking place in our world today. It is a social revolution, sweeping away the old order of colonialism. And in our own nation it is sweeping away the old order of slavery and racial segregation … And so we see in our own world a revolution of rising expectations. The great challenge facing every individual graduating today is to remain awake through this social revolution.”

King referenced well-known Christian scholars and Jesus himself throughout the speech, suggesting “some of the things that we must do in order to remain awake and to achieve the proper mental attitudes and responses that the new situation demands”.

One of those suggestions was “achieve a world perspective,” learning to “live together as brothers” to avoid the scenario where “will all perish together as fools.”

Another, that “we work passionately and unrelentingly to get rid of racial injustice in all its dimensions,” listing the changes that have already been made (desegregation of schools, the Civil Rights Bill, and voting rights legislation) and those that were still needed (housing equality, economic disparity, schools, and racialised violence and murder).

“Anyone who feels that our nation can survive half segregated and half integrated is sleeping through a revolution,” he says. He goes on to say that time alone would not produce change.

But for King, the most important reason for people to stay awake to racial injustice was a straight-forward spiritual one: racial injustice is sin.

“Segregation is morally wrong, to use the words of the great Jewish philosopher, Martin Buber, because it substitutes an I-it relationship for the I-thou relationship. Or to use the thinking of Saint Thomas Aquinas, segregation is wrong because it is based on human laws that are out of harmony with the eternal natural and moral laws of the universe. The great Protestant theologian, Paul Tillich, said that sin is separation. And what is segregation but an existential expression of man’s tragic estrangement – his awful segregation, his terrible sinfulness?” King said.

As he drew the speech to a close, King turned to the wordsmiths, quoting a gospel songwriter, a poet, a poet-turned-journalist, the biblical prophet Amos, and an unnamed, old Black slave preacher. The result? Comments King might well have penned to Christians today.

“In the struggle for racial justice the Negro must not seek to rise from a position of disadvantage to one of advantage, to substitute one tyranny for another. A doctrine of black supremacy is as dangerous as a doctrine of white supremacy,” he said.

” … God is not interested in the freedom of black men or brown men or yellow men. God is interested in the freedom of the whole human race, the creation of a society where every man will respect the dignity and worth of personality.”

King told his listeners that he is still able to sing the lyrics of the old hymn “We shall overcome” because he has “faith in the future”.

“We will win our freedom because both the sacred heritage of our nation and the eternal will of God are embodied in our echoing demands,” King said. “Yes, we shall overcome because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice …”.

For King, it was clear – racial reconciliation was God’s own work of justice and Christians should stay spiritually awake to it. Ironically for white Christians today, that probably means giving up flippant use of the word woke.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?