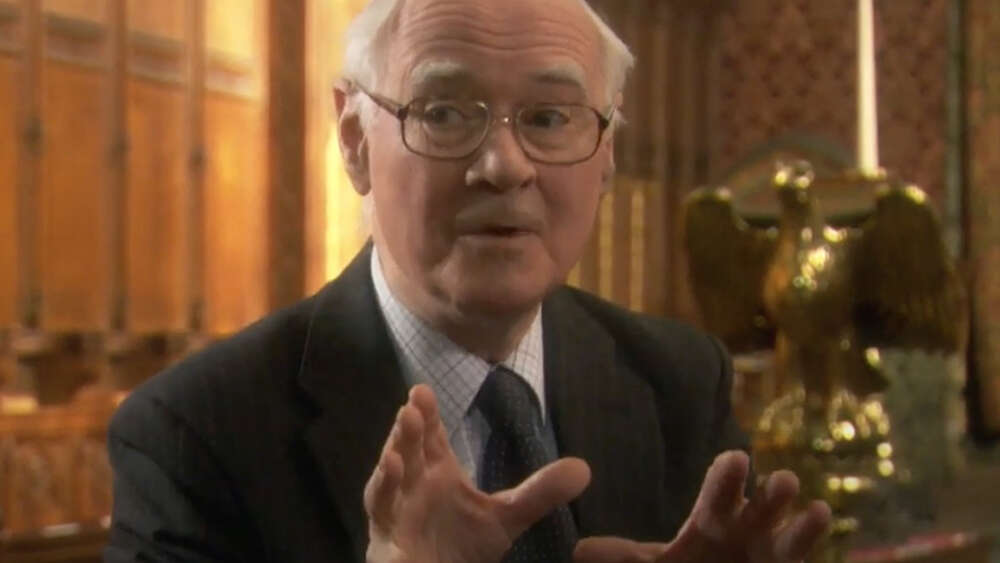

A giant who reconciled science and religion

The legacy of John Polkinghorne from one who knew him

In 1979, the international scientific press announced the shocking news that a Cambridge university professor of mathematical physics was resigning to become a priest!

They were referring of course to John Polkinghorne, who died last week at age 90.

Polkinghorne was both a renowned physicist and an Anglican priest who did much to reconcile science and religion. For him, there was no serious conflict between his commitments as a world-class scientist and his deep Christian faith.

A lifelong Anglican, Polkinghorne studied mathematics at Cambridge where he was the top mathematics undergraduate. After appointments in the US and Scotland, he returned to Cambridge, ultimately becoming professor of mathematical physics in 1968. He was elected to the prestigious position of fellow of the Royal Society in 1974 but, by 1979, he felt that he’d done his best research. He resigned his position and announced he was heading to Anglican ordination.

In 1984 he published the first of his 27 books at the faith–science interface, The Way the World Is. His aim was firstly to explain to scientists the basis of his faith, and secondly to show how a thinking person could be a Christian.

In 2002 Polkinghorne won what was perhaps the world’s richest award, the Templeton Prize for progress in religion.

Visits to Australia

Polkinghorne came to Australia many times, visiting Melbourne in 1993, 1995 and 1998, where I was privileged to host him often at Monash University.

His 1993 visit, at the invitation of ISCAST – Christians in Science and Technology, saw approximately 100 people at his public lecture in Melbourne. At Monash he also presented a lunchtime talk on faith and science, attended by over 150 people. He also gave a lecture to students and staff from Monash physics called “Six Problem Areas in Physics”.

On his third and final visit to Monash in 1998, a particular highlight was a lunchtime lecture on the nature of reality to an audience of 200. His visit culminated in a dinner in his honour attended by about 20 people, including Anglican Archbishop Keith Rayner. Although we had a good discussion about the place of faith–science issues in the training of clergy, those present who were involved in theological education, including the Archbishop, could not see where it would fit in the curriculum!

Polkinghorne’s lectures were always lucid, presented in a language that a well-educated audience could comprehend. This was exemplified in the kinds of questions that his lectures generated. Always gracious, he had a great capacity to turn dumb questions into something significant by engaging with the questioners and saying something like, “Have you thought of it this way?” or “Perhaps this raises a deeper issue.” Such questioners went away several feet taller! A rare gift.

Polkinghorne’s generous orthodoxy

Theologically, while Polkinghorne held a very orthodox Christian position, he had the rare gift of engaging with people from across the broad Christian spectrum. This orthodoxy is most eloquently expressed in Science & Christian Belief: Theological Reflections of a Bottom-up Thinker. In the book, he reflects on the Nicene Creed, both theologically and scientifically, in the light of the best of modern science.

Polkinghorne also placed much emphasis on the centrality of the resurrection as a strong basis for hope. Aspects of his thought may be found in Tom Wright’s Surprised by Hope.

He was also able to engage with other faiths without compromising Christian faith. He often reminded us that different faith traditions actually make rather different truth claims. But for him that was a reason to keep dialogue open.

John Polkinghorne gave heart to those of us who were Christians and scientists in academia.

After 1979, Polkinghorne focussed on encouraging and enabling good conversation and dialogue amongst and between scientists and theologians. The establishment of the International Society for Science and Religion was consistent with this, and he served as its first president.

A commitment to truth

Polkinghorne certainly believed in the unity of knowledge; the task of science was to describe a unified reality that we encounter in our experience. Further, he was a critical realist who believed that truth, whether scientific or theological, needs to be carefully assessed. In the following we get a taste of some of his key insights:

“If we are seeking to serve the God of truth then we should really welcome truth from whatever source it comes. We shouldn’t fear the truth … The doctrine of creation of the kind that the Abrahamic faiths profess is such that it encourages the expectation that there will be a deep order in the world, expressive of the Mind and Purpose of that world’s Creator. It also asserts that the character of this order has been freely chosen by God, since it was not determined beforehand by some kind of pre-existing blueprint … As a consequence, the nature of cosmic order cannot be discovered just by taking thought … but the pattern of the world has to be discerned through the observations and experiments that are necessary in order to determine what form the divine choice has actually taken.” (Quantum Physics and Theology: An Unexpected Kinship, 2007).

There are two particular insights of Polkinghorne that stand out for me.

Polkinghorne’s free-process defence

Polkinghorne’s “free process defence”, which he articulated very skilfully, may well turn out to be one of his more profound contributions. By extending his arguments about human free-will to the whole universe, he was able to understand that the processes in the universe from the big bang until now have a level of genuine openness (Science & Providence: God’s Interaction with the World, 1993, pp. 65–67). In this context he also said, “God didn’t produce a ready-made world. The Creator has done something cleverer than this, making a world able to make itself” (Quarks, Chaos & Christianity, 1994).

“I believe that a full understanding of this remarkable human capacity for scientific discovery ultimately requires the insight that our power in this respect is the gift of the universe’s Creator who, in that ancient and powerful phrase, has made humanity in the image of God (Genesis 1:26–27)” (Quantum Physics and Theology: An Unexpected Kinship, 2007).

The relationship between knowing and being

Another of Polkinghorne’s insights was his frequent claim that “epistemology models ontology”. In other words, what we know about the world represents the reality it seeks to describe. He further argues that “anyone who wishes to speak of agency, whether human or divine, will have to adopt a metaphysical point of view” and “metaphysical views are ontologically serious. They seek to describe what is the case” (Chaos & Cosmology: Scientific Perspectives on Divine Action, 2000, pp. 148-9).

In this context he also said that it is God’s faithfulness that allows our knowledge to model how the world really is. What this means is that there are in fact gaps in our knowledge of reality, resulting from indeterminacy at the most basic level of matter: quantum indeterminacy. And he was always careful to remind us that we mustn’t confuse epistemological ignorance (gaps in knowledge that might one day be uncovered) with ontological unknowability – those things which we cannot know in principle.

A lasting legacy

John Polkinghorne gave heart to those of us who were Christians and scientists in academia and, particularly through his many books, gave us new tools for talks, conversations and for engaging with others about science and Christian faith.

I count it a great privilege to have known him, and I have benefitted enormously from his contributions and insights. He articulated ideas many of us may have reached independently, but he made them more accessible.

We shall miss a true, gracious and generous Christian and we are all the better for his example. His many books and insights will continue to help us explore the interaction between Christian faith and modern science.

John Pilbrow is former head of physics at Monash University and a former president of ISCAST – Christians in Science and Technology.

A longer version of this article can be found on the ISCAST website at www.ISCAST.org/Polkinghorne where you will also find details of an ISCAST event in appreciation of John Polkinghorne’s life and work. It will be online, probably on April 10, 2021.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?