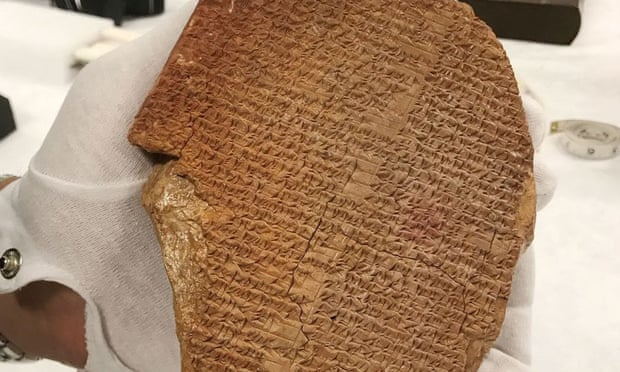

A rare, 3600-year-old tablet bearing a portion of the ancient poem, the Epic of Gilgamesh, has been seized by the US government from craft retailer Hobby Lobby and is on its way back to Iraq, following a US court ruling that it was obtained illegally.

Hobby Lobby’s billionaire president, Steve Green, is also the chairman of the board of the Museum of the Bible in Washington DC. Green bought the tablet for close to $US1.7 million to display in the Museum, but the Department of Justice says it was sold under a false provenance (history of ownership) and is probably an artifact looted from Iraq during the chaos of war,

An auction house sold it to Hobby Lobby with false provenance documents.

The Epic of Gilgamesh is an ancient Mesopotamian text that is considered one of the world’s oldest religious and literary texts. The poem was originally inscribed on 12 clay tablets in cuneiform script, a logo-syllabic script that can be traced back to the end of the 4th millennium BC.

The US Department of Justice said the rare tablet, known as the “Gilgamesh Dream Tablet”, originated in the area of modern-day Iraq and entered the United States contrary to federal law. An auction house sold it to Hobby Lobby with false provenance documents. In a statement seen by The Washington Post, the Museum of the Bible said it had been working with federal authorities since learning of the dubious travel history of the tablet and that Hobby Lobby was suing the auction house for the money it spent on the tablet.

“The museum was informed in 2019 of the illegal importation of this item by the auction house and previous owners. Since then, we have supported the Department of Homeland Security’s efforts to return this Gilgamesh fragment to Iraq,” the statement read.

The tablet has begun its journey back to Iraq, a similar journey to thousands of other Iraqi antiquities – 17,000 to be exact – which arrived in Baghdad from the United States earlier this month.

About 12,000 of the returned items came from the Museum of the Bible. At just four years old, the Museum has been plagued by controversies regarding its collection.

“I trusted the wrong people to guide me, and unwittingly dealt with unscrupulous dealers in those early years.” – Steve Green

In March 2020, Steve Green admitted he had made mistakes in his early days of collecting biblical manuscripts and artifacts. “I knew little about the world of collecting,” he wrote in a statement. “It is well known that I trusted the wrong people to guide me, and unwittingly dealt with unscrupulous dealers in those early years. One area where I fell short was not appreciating the importance of the provenance of the items I purchased.”

Green said that curators at the Museum of the Bible had been “quietly and painstakingly” researching the provenance of the many thousands of items he had collected since 2009. The research identified almost 12,000 items – papyri fragments and clay objects – that had “insufficient provenance”, and would be returned to their places of origin – Egypt or Iraq. He said the Museum and Hobby Lobby were working with the US government to determine the best way to handle that process.

The Museum of the Bible is not the only institution to contend with issues surrounding the repatriation of looted artifacts. The renowned ‘Benin Bronzes’, from the ancient kingdom of Benin (now southern Nigeria), were looted by British troops in the 19th century and now can be found scattered through Western museums, including the British Museum. The Washington Post also reports that dabbling in the grey market for antiquities is much risker these days, with fundamental changes in the laws, norms and institutions regulating the trade in stolen and looted art over the past three decades. Artifacts from Iraq are under particular scrutiny, given reports that Islamic State sold off important artifacts to fund its war efforts.

After many problems, however, “The Museum of the Bible is now setting an example for responsible ownership of foreign cultural heritage,” write law and history academics Anja Shortland and Daniel Klerman for the Post.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?