Friday, 29 June 2012

~~It was more gentle than any theft

Too gentle to believe~~

Aidan Coleman was 31 when a stroke stole his words. It took much more than that – it almost took his life. But for a poet, words are pretty important.

“When I woke up after the stroke, I was surrounded by friends and family and I thought, ‘something pretty bad’s happened’. I went to ask a question, and no sound came out of my mouth.”

The night of the stroke, Coleman’s wife Leana was told it was 50/50 as to whether he would live. So when Aidan regained feeling in his legs, it was a good sign. But speech, says Coleman, came back very slowly.

“When it did come back, it was broken words. They were all out of order.”

Now, years on, Coleman says he still has trouble breaking words down into syllables. He’s worked as an English teacher, has written several textbooks on Shakespeare since his stroke and has just taken on the role of speech writer for the South Australian government. But reading aloud will never be as it was before.

“I spent a year rebuilding my speech. I can’t deliver Shakespeare as well I used to. To read a poem aloud, I have to practice a lot.”

Coleman says he’s always been a poet. His poetic bent showed first at primary school, where he chose poetry – most typically limericks – to complete writing tasks. Later on, after reading the Romantic poets in high school – as well as Wilfred Owen, TS Eliot, Hopkins – he tried his hand at a similar style.

“I tried to write Eliot-style about mediocrity, old age, the meaning of life. That didn’t work very well,” says Coleman.

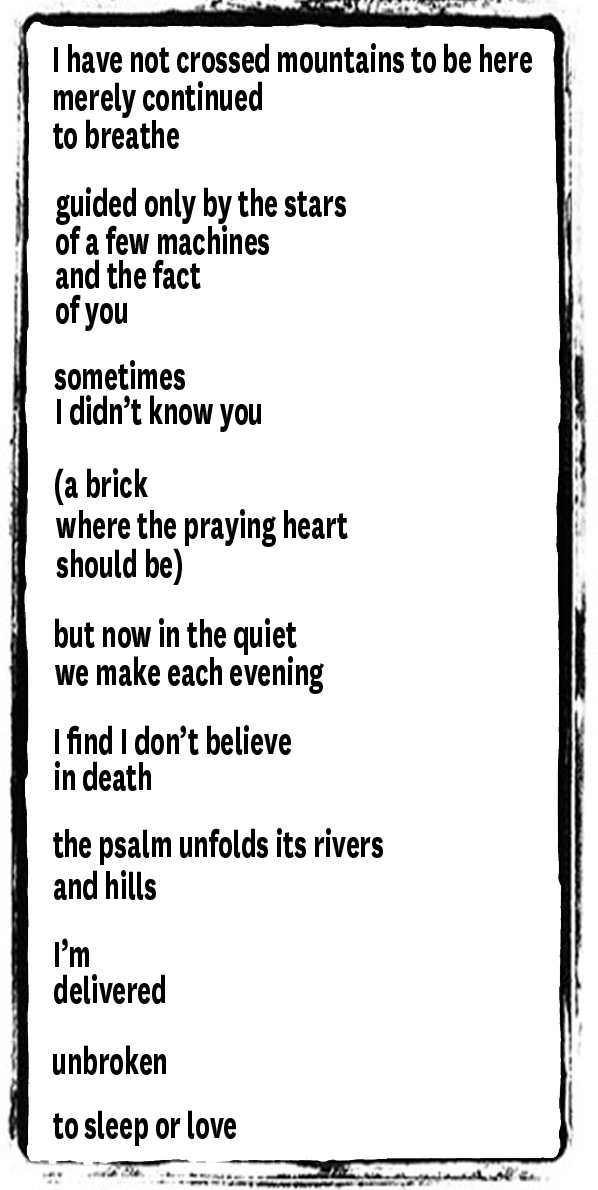

Fast forward 20 years and Coleman has found his stride in a more direct poetic style. His latest anthology of poems, Asymmetry, was launched at Sydney Writer’s Festival in May. The first part of the collection takes the reader on a journey through Coleman’s stroke experience. The second part is devoted to his wife.

“After the stroke, I thought I’d lost the ability to create metaphor. But, after about nine months I started writing again. I wrote love poems to my wife. I wasn’t ready to visit the darkness of the stroke.”

It took a couple more months before Coleman was able to approach his stroke through his writing. In the resulting collection the metaphorical abounds and the feeling shouts, despite its brevity.

“I really like image and metaphor. I like poetry when it does the most it can with only a few words. I’ve always found that appealing. I think poetry is most successful when it’s most itself and least like prose. I think all of those things have transferred over to the new collection.”

As a Christian, Coleman doesn’t wrestle with balancing Christ and the words on the page.

“I feel [my Christianity] touches every poem that I write – it’s there in the voice and in the person behind the poetry.”

Coleman says poetry doesn’t have to be devotional to display Christianity.

“You can authentically write about belief more easily in poetry – it’s much more personal than a novel. And, if you’re a Christian, I don’t think it’s possible for Christianity not to be central.

“But I think it’s the whole package with a poet. I can pretty much get a feel for a poet’s beliefs without them touching overtly on faith or politics in their writing.

Coleman says Christianity in his new collection is illusory, but ever present.

“A novelist writes about characters, but poets write about themselves as the character. The more a person reads a poet’s work, the more they get a feel for the character of the writer.

“I don’t think it’s possible to write well and the soul not to be on show. That’s different from being overtly Christian. We distrust literature that has designs on us, so if [our own beliefs] are too obvious or didatic, people will distrust the poem. It’s got to be digested in the poet’s own voice, in his or her words.”

Coleman likes to think of himself as a lyric poet in the Romantic tradition. In his writing, he’s not concerned with theology or apologetics. In fact, he says, “as soon you enter into the realm of argument, it’s probably not good poetry.”

And while he knows some will disagree – “some people would say that’s an impoverished definition of poetry” – he believes Romantic poetry at least is more about connecting with feelings on a personal level.

“A lot of people would describe me as a love poet. I really like that. Love poetry can be really affirming. I think my love poems to my wife in the new collection celebrate monogamy and that special intimacy.

“Often love poems can cross over from the erotic to the divine and many of my favourite Christian poets work in this fertile territory.”

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?