A lifetime of helping Indigenous Christians meet God in language

Mally McLellan grew up in a family where a constant stream of missionaries from across the world stayed in their home in Gympie, Queensland, while having meetings in the town. It was a setting that inspired her three older siblings to serve the Lord in different parts of the world – from Venezuela to Kalimantan – but as the youngest, Mally (Marilyn) was determined to be different.

“I was saying firmly that I wasn’t going to be a missionary because all the others were missionaries and I wasn’t going to just copy them. But the Lord had put the cross-cultural enjoyment in me through all these missionaries passing through,” she says.

She marvels at how God pulled all the threads of her varied experiences into a harmonious design.

Marilyn McLellan is talking to Eternity on the chapel veranda at Nungalinya College in Darwin, the college for Indigenous Christians, where she has assisted in teaching the Diploma of Translation since 2019. But as she relates her long and distinguished career, over 40 years as a teacher/linguist/Bible translation facilitator, primarily in Indigenous languages, it is clear she will be sorely missed when she goes home to Queensland soon to retire.

As we’re talking, she marvels at how God pulled all the threads of her varied experiences into a harmonious design that came together in two main career achievements.

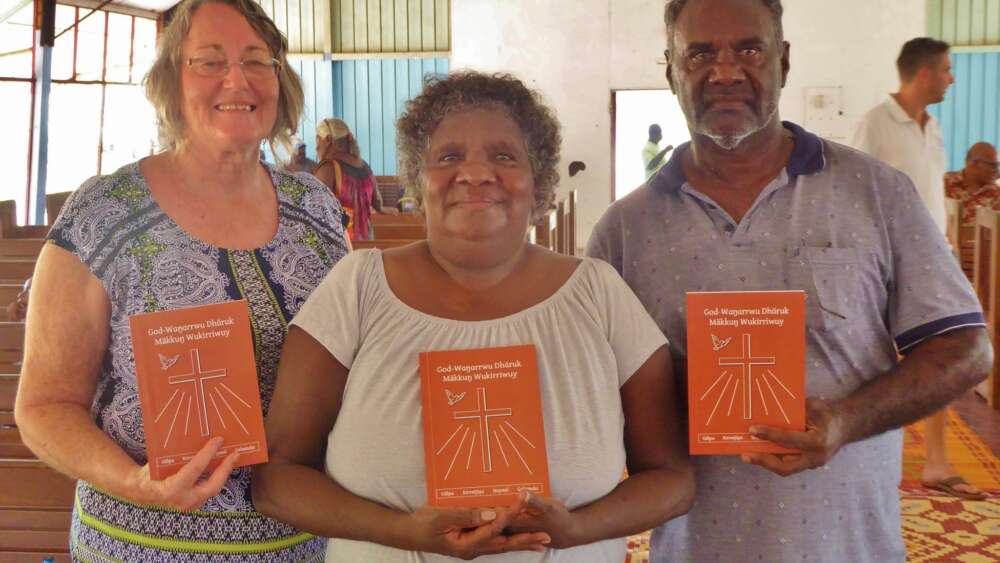

Mally McLellan with her Aboriginal sisters at the dedication of the Gospel of Mark in Wangurri at Dhälinybuy in November 2017.

One was teaching the ground-breaking CIT – Certificate III in Translating (Indigenous) – to several Indigenous language groups. This was a course developed by SIL-AAIB (now AuSIL) to train Indigenous translators to translate into their own languages. It was a Vocational Education and Training (VET) course and was the first of its kind in Australia. It was also taken up by Indigenous translators in Vanuatu and developed into a Cert IV.

“It was an excellent course and we have used some of it as a basis for the new Certificate II in Translating that we are hoping will be approved as a VET course to be introduced at Nungalinya next year,” she explains.

“CIT was originally developed because the Indigenous translators expressed the need for training, and then said they’d like it to be government recognised. That’s when it had to go through the rigours of VET requirements.”

Another of Mally’s career achievements occurred while working with the Aboriginal Resource and Development Service (ARDS, an NGO under the Uniting Church. There she worked as linguist with a team of medical and Indigenous experts to create an anatomy dictionary in plain English and Djambarrpuyngu, the dominant language of North Eastern Arnhem Land.

Its production required the blending of knowledge from two world views, the biomedical understandings of the Western world with the world view and understandings of the Yolŋu world in relation to the intricacies of our bodies and how they work.

“It was not always an easy blend, but it was stimulating working through the issues as we each came to an understanding of the other’s world.”

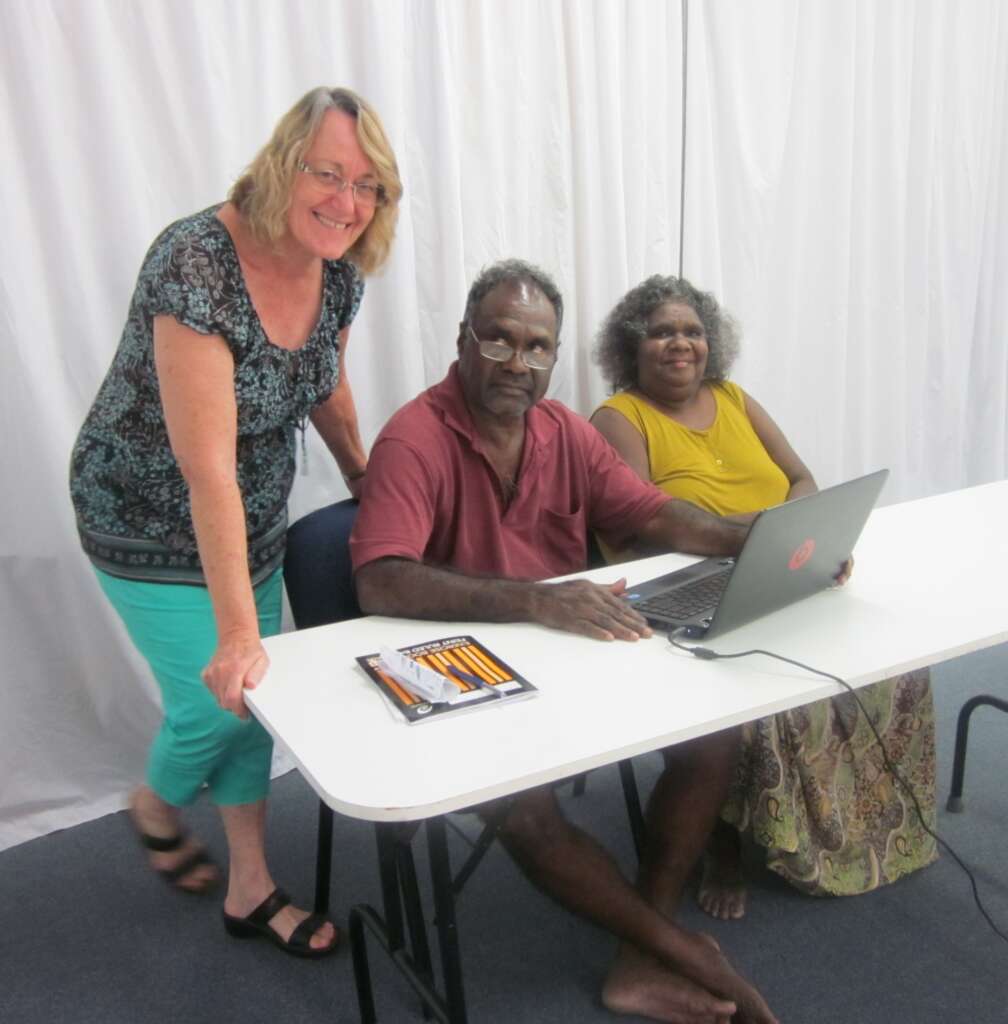

Advising translation: Mally with Djawuṯ Goṉḏarra, the translator, and his wife, Yurranydjil Dhurrkay, an experienced translator who is an adviser to several translation projects into Yolngu languages

Her Nungalinya colleagues will miss her greatly, not only for her expertise but also as a storyteller. She has a fund of anecdotes about her Aboriginal family and the highlights of her time in various Aboriginal communities, supporting Indigenous Bible translators.

In one such display, Mally tells me about the time her Aboriginal father reacted with indignation when he heard a section of the Bible for the first time in the Djambarrpuyngu language.

Like many whitefellas who work long-term in the Territory, Mally was adopted by an Indigenous family. It was while she was doing research into Wangurri, a Yolŋu language of NE Arnhem Land in 1988-89. She was living with her cousin, Dianne Buchanan, a Bible translator for Djambarrpuyngu, another Yolngu language. They visited a homeland with her Aboriginal “dad” and some of his family.

“He said, ‘How long have we had missionaries here? They’ve been here more than 40 years and we’ve never heard this before!’”

Di wanted to check one of Paul’s letters, probably Romans, to see if they comprehended what had been translated or whether the wording needed to be changed to improve the flow.

“As Di was reading this out, my Aboriginal dad suddenly sat up and there was this real anger in him. He said, ‘How long have we had missionaries here? They’ve been here more than 40 years and we’ve never heard this before!’” she says.

“Then he calmed down and he said, ‘but then, we don’t know enough English to understand this and they don’t know enough of our language to teach this in our language.’

“So English-speaking missionaries never knew the depth of Djambarrpuyŋu that you need for these teachings. You can talk at a surface level and they’d probably even gone one below that surface level, but they hadn’t been able to get to the depths of theological teaching.

“The missionaries had a love for the word … but you had to be there for a very long time before you got to the level of being able to teach theological truths in language.”

It’s an anecdote that starkly illustrates why Bible translation remains so important.

“We don’t just need one worker – we need droves of workers, but one would do.”

Mally’s retirement comes soon after the recent, untimely death of Cathy Bow, a key Indigenous language researcher/linguist in the Top End, last year. The loss of both women’s work has highlighted a crying need for more workers prepared to make a long-term commitment to support Indigenous language Bible translation in the NT.

“We don’t just need one worker – we need droves of workers, but one would do,” reflects Mally plaintively.

Mally’s own fascination with Indigenous languages began when she was a science teacher at a high school in Papua New Guinea between 1973 and 1975.

“Now in that school there were about 400 high school students and they came from 40 different language groups. Papua New Guinea is a really amazingly diverse country, linguistically. They have about 800 languages. It is mind-blowing. And to teach effectively, you need to know how your students think. And everyone thinks through their own language,” she recalls.

Mally had such a good time in Papua New Guinea that she decided to go to Bible College back in Queensland with a view to returning to PNG.

However, after doing a two-year missions diploma at Kenmore Christian College in Brisbane, Mally embarked on a year of teaching at Kowanyama, an Aboriginal community on Cape York.

At Kowanyama, Mally observed how her students struggled to learn in English, their second language. And despite residing in Australia, she felt more isolated there than she had in the remotest parts of PNG because the only contact with the outside world was with the police radio. She was also troubled by the pernicious influence of alcohol abuse in the community.

“It was a tough and dreadful year. It wasn’t the exciting time that I’d had in Papua New Guinea, but I think a seed was planted there. And my cousin, who was working on the Djambarrpuyngu Bible translation on Elcho Island and could see with concern the tough time I was having, said to me, ‘I really want you to come over here, Mally, just so you can see there’s another side to Aboriginal communities [because Galiwin’ku doesn’t have legal alcohol]. So I went and visited her for a week and had a lovely time.”

“I took to linguistics like a duck to water. I just loved it. I loved the analysis side of it and I loved the cross-cultural learning.”

Two years later, in 1982-83, Mally discovered her abiding love while doing a 10 week SIL (Summer Institute of Linguistics) course in linguistics held over summer holidays at New College, University of NSW.

“I took to linguistics like a duck to water. I just loved it. I loved the analysis side of it and I loved the cross-cultural learning,” she explains.

So a year later, Mally went back to do the SIL advanced course at Wycliffe Bible Translators’ headquarters in Victoria. At the end of that course, she seemed to be the only one in her group who didn’t know the path she was being called to.

But while she was on summer holiday, she received an offer of a short-term position tutoring in phonetics and language learning at the SIL School in Kangaroo Ground, Victoria. That turned into offers to teach more courses, but after two years, the Principal encouraged Mally to embark on postgraduate linguistic studies. It was hoped that she would return one day to teach full time. But Mally, who describes herself as “a tropical body, I love the outdoors”, decided she couldn’t forgive Melbourne for its weather.

She embarked on postgraduate linguistics at Sydney’s Macquarie University which eventually led to a PhD into the Wangurri language, involving pioneering research at Galiwin’ku on Elcho Island.

“It was a grammatical analysis of the Wangurri language, majoring in the verb forms. And the thrust of my thesis is that there actually isn’t tense. The basis to make a sentence finite, or not, is what we call modality – is it real, has it happened or has it not happened? That’s how they divide it.”

In 1992, as she was submitting her thesis, she received an invitation to teach linguistics at the Centre for Australian Languages and Linguistics at Batchelor, about an hour’s drive south of Darwin. She taught there for three years, but commuting by bus every day from Darwin to Batchelor took its toll, and Mally burnt out.

Mally took the following year off work to recover, and it was during that year, that the most significant element of her career began to germinate.

In the late 80s and early 90s, SIL translator and researcher Dr Christine Kilham responded to requests by Aboriginal people to be trained to translate by developing the ground-breaking Certificate in Translating (CIT) course.

Tragically, Christine died of cancer before the course could be accredited, but Susanne Hagan and Ann Eckert continued the development of CIT to turn it into an accredited course.

“I love grammar. And so do the translators. They love to see that their languages have a pattern to them.”

In August of 1995, Mally was asked to teach grammar at a CIT combined workshop with Djambarrapuyngu, a Yolngu Matha language, Kriol and Kunwinjku.

“Well, that was my first love. I love grammar. And so do the translators. They love to see that their languages have a pattern to them. That there are rules that they’ve got in their head and they didn’t even realise.”

By the end of that year, Mally had come on board as part of the SIL Aboriginal and Islander Branch team to teach CIT to Indigenous Djambarrpuyngu Bible translators.

“I stayed there for nine years and it was the pinnacle of my career. I just loved it. I finished with the Djambarrpuyngu translators in 1998 and then started with a second round of Kriol people, who graduated in 2000, and then when they finished, I took the Wubuy group through.

“I could look back and think, well, all those threads have come together – the cross-cultural training that the Papua New Guineans gave me and the linguistic training that I’d had and the teaching of it in Kangaroo Ground. Even Bible college, my teaching, all of these strings were coming together and they all sat together nicely with CIT. So that was lovely.”

For six months in 2004, Mally worked as the education linguist for East Arnhem, where there were four bilingual schools – at Numbulwar, Galiwin’ku, Yirrkala and Milingimbi – supporting their teacher linguists. This was followed by two years as teacher-linguist in Galiwin’ku.

Mally notes with great sadness that there is barely any bilingual education in NT schools today.

“The thing is, the kids come to school, not talking English, and they are suddenly supposed to understand everything just when they’re at the age where they should be doing language development and concept development in their own languages.

“They should grasp the concepts first in their own language. And then when they learn another language, [in this case English], they can attach the new language to the concept that they already know. Instead, they’re learning another language which interferes with their concept development. And it’s just wrong.”

“If they’re willing for their minds to be opened to a whole other way of thinking, that’s what it is to work cross-culturally.”

I finished our interview by asking Mally what she would say to encourage people down south to come up to the Territory to commit to long-term linguistic work in Indigenous languages

“God creates people to love what he calls them to. God made you for your job. And he made me for mine. I think people have to have a sense of adventure because there’s going to be a lot of confronting stuff. If they’re willing for their minds to be opened to a whole other way of thinking, that’s what it is to work cross-culturally. And they need to have a deep burning desire for God’s word to get out.”

“There’s a mighty lot still being spoken that don’t even have the New Testament, or even one book of the Bible.”

She points out that there are roughly 90 translations of the Bible in English, yet many languages in Australia have none.

“In Australia, there’s only one and it’s Kriol. None of the traditional languages have got the whole Bible yet, though a few have some books of the Old Testament. Only 15 have the whole New Testament, and there’s a mighty lot still being spoken that don’t even have the New Testament, or even one book of the Bible,” she says.

“So if you’ve got a sense of the place of God’s word in your own life and then recognise that there are a lot of Christian people who don’t have that luxury, please come. You need to have fire in the belly for God’s word and a sense of adventure about going to places you never thought of because going cross-culturally is adventure. You will need a willingness to learn from other people who our society often doesn’t learn from.

“Recognising, too, that these people might not be dressed as if they’re going to see the Queen, but they have got sharp minds. And we need to have listening minds. We need to always be listening.”

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?