Greg Sheridan regrets not talking about God enough

… to the world leaders he interviewed

In his long and illustrious career as Foreign Editor of The Australian newspaper, Greg Sheridan has had fireside chats with many world leaders who occasionally confided in him about their religious beliefs.

Now, the journalist and author regrets having been so cagey when God came up during these political conversations, and wonders if he might have been able to do some good if he had been more open about his own faith.

“I was shy about my own belief, not wanting to put myself forward as an example. I was a bit cagey, I wanted to dig to make confessions about politics. And so I didn’t really respond to them as warmly or as proactively as I could have done,” he tells Eternity in a Zoom interview from his home in Melbourne.

“And I think, ‘well, for goodness’ sake, you could have been a bit more straightforward about it.’ If somebody asked me my opinion about, you know, Chinese foreign policy or something, I’d just spill out everything without the slightest hint of shyness. So there’s no reason.”

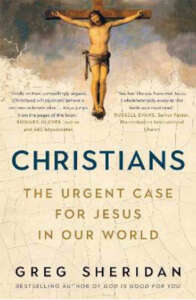

Sheridan has now well and truly come out of the closet as a highly public Christian in his new book, called appropriately enough Christians. In the first half, he gives a lively, witty and ridiculously readable defence of belief in Jesus, the broad historicity of the gospels and the sheer fun of encountering the vibrant characters of the Bible.

In his previous book, God is Good for You, Sheridan mounted an intellectual defence of belief in God in a culture of waning Christian belief in the West and dusted off the covers on the Old Testament, finding much joy and delight therein.

I mean, people don’t get enough of the fun of the Bible.

However, some commentators took him to task over the fact that they didn’t get a chance to meet the real Jesus. This inspired Sheridan to rectify the gap and spend a year or two reading the New Testament in detail.

“What fun it was. What a happy assignment,” he writes in the Preface to his book.

“You know, it’s all fun,” he repeats in our interview. “I mean, people don’t get enough of the fun of the Bible. You know, I love it when Paul says, ‘I wish these people would castrate themselves.’ You know, there are various ways of interpreting that. And he’s obviously having a bit of fun. I like Peter saying ‘Paul can be a bit hard to understand and can be a bit difficult, but you’ve got to put up with him because he’s my beloved brother – he’s an apostle writing in the Scriptures.’

“In my professional time as Foreign Editor, I am concerned primarily with the Chinese Communist Party and Donald Trump and Joe Biden and the Defence budget and so on. So it’s a positive, fabulous joy to spend time in the New Testament with Jesus and Paul and Mary… I love the agency of Mary, you know – Mary, I think, is a much more active figure than either her devotees or the people who think she gets too much attention, really give credit for… So I got really absorbed in the New Testament.”

Sheridan, a lifelong Catholic, found the experience reading the New Testament in detail “kind of revolutionary”.

“I was struck by the urgency of the crucifixion, just the immediacy of it, the starkness of the account, you know, and I think that’s the most extraordinary thing about Christianity, even more so than the resurrection,” he says.

“I mean, other religious sensibilities have had gods or who are incarnated. They haven’t had anything quite like Jesus Christ. You know, Krishna walked on the earth and all that sort of thing. But it hasn’t been historical. It’s been in the time before history and so on. The idea that God could conquer death in the normal religious sphere was almost ubiquitous in human consciousness, but the idea that the everlasting, omnipotent, omniscient, all-powerful, immortal God could suffer humiliation, torture, beating and death. You don’t find that in any part of any human religious sensibility. So the crucifixion struck me as just the most astonishing thing.”

The second half of Sheridan’s admirable new book contains profiles of contemporary Christians, notably a long interview with Prime Minister Scott Morrison, who reveals that he prays on his knees every day as well as ad hoc prayers. Another interview is with former Labor leader and governor-general Bill Hayden, who came back to Christian faith after a long period as a conscientious atheist.

Given the lively evangelistic tone of the first half of the book, I ask Sheridan what effect he hopes it will have.

“I hope that it confirms and helps Christians. And I hope that people with an open mind who aren’t Christians might read it, or people who used to be Christians and have fallen away, might give it some thought and people who are actively hostile to Christianity might read it and think, ‘well, okay, maybe it’s worth looking again at the account of the crucifixion in the Christian gospels. what can I get from that?”

“If the book had the effect of getting people to read the Bible, read the New Testament, particularly, for themselves, that’d be the best effect of all, because the best Christian scholarship in the world is not as good as actually reading the gospels and the epistles themselves.”

While all the gospels are fantastic, he says, his favourite is Luke.

“I love the Gospel of Luke. I think it’s the warmest of the gospels … I love the letter to the Galatians. I love it. The vigour and vim of Paul. I love John’s writings, the first letter of John and also John’s Gospel. John’s voice is so distinctive – it’s not like anything I’ve ever encountered in human literature anywhere else.”

All the good things we like in Western civilisation – human rights, liberalism equality of the sexes – are realisations of Christianity.

People need not be intimidated by the New Testament, he insists. “Just read it one book at a time. Luke’s Gospel and then read another one. Even the longest of the epistles is only 10 or 11 pages, so it’s not as if you’re going to exhaust yourself.”

The book is subtitled The Urgent Case for Jesus in our World, and though Sheridan acknowledges that Christianity is on fire in many parts of the world (he includes two chapters on China), he fears that its repudiation by the West holds dangers for our civilisation.

“Western civilisation owes an enormous intellectual and cultural debt to Christianity,” he says.

“Of course, in the course of Western civilisation Christians did a lot of bad things. No question about that. I’m not contesting that for a second, but all the good things we like in Western civilisation – human rights, liberalism, equality of the sexes – are realisations of Christianity.

“For a long time, a culture can live on the moral capital of Christianity. It has the assumptions of Christianity. It still uses the categories of Christianity, but a lot of things, which even a generation ago in the West were regarded as self-evident given ideas, universal human rights and so on. These are really ideas that come from Christianity. And if you totally cut these ideas off from their roots, I think it would be very hard to sustain the ideas.”

Nevertheless, Sheridan ends his book on an optimistic note, recounting new movements, new growth signs of life, in churches all over the place.

“Jesus told us that the gates of hell will never prevail against his church. And it is also the fact that we follow a God that found his way out of the grave; you know, God is cleverer than his enemies. He finds his way into human hearts and human beings find their way to go on,” he says.

“There’ve been times in the past when the prospects of Christianity have looked much bleaker than they do now, Nicky Gumbel, the great progenitor of the Alpha course in London – wonderfully impressive guy, fantastically interesting pastor. He tells me about the state of Christianity in England in 1750, when there were 16 people who went to Easter services in St Paul’s Cathedral, 10,000 sex workers walking the streets of London; and then along came the Wesleys and Wilberforce and there was this magnificent revival throughout England, thousands, hundreds of thousands, millions of people coming to Christ.

“That shouldn’t make us complacent, but it should give us a lot of inspiration. You know, we’ve had rough times before and it’s at rough times that the Christian tradition often does the most unexpected things, the cleverest things, and I don’t think there’s any reason to be pessimistic and not only that, I’m Irish, so situation desperate, right?

“The advantage, we have is we’re actually telling the truth. There is a constituency for the truth in every human. So whatever advantages our competitors or enemies might have, you know, control of the heights of communication, whatever it might be, we have this tremendous advantage that human beings want to respond to this truth.”

Christians:

Christians:

The Urgent Case For Jesus in Our World

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?