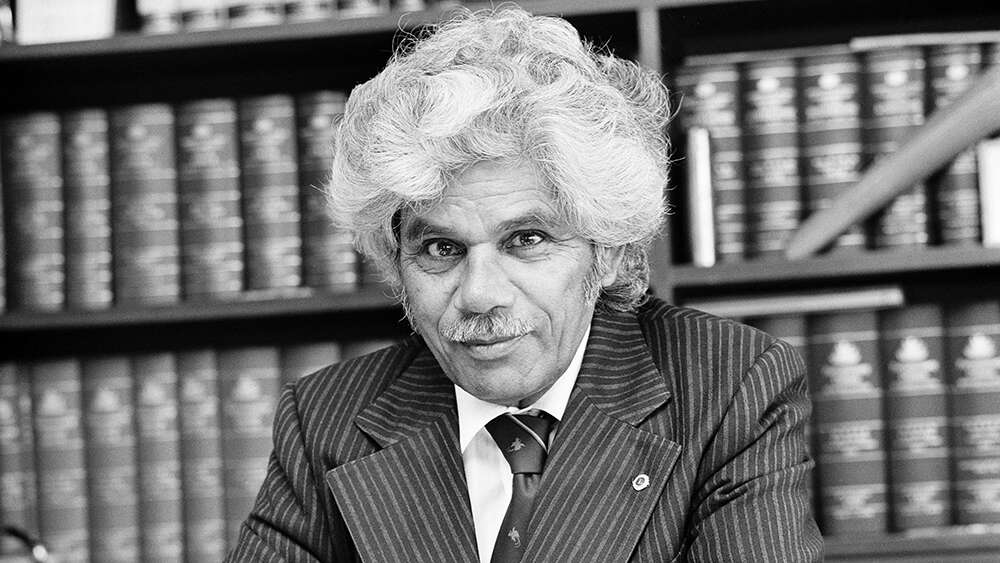

Remembering the 50th Anniversary of the first Indigenous Australian to sit in Federal Parliament

Half a century ago this month, our first Indigenous Australian entered Federal Parliament as a Senator for Queensland. On 17 August 1971, a Jagera man born beneath a palm tree, took his seat for the first time on the red leather of the Australian Senate. As well as being a national trailblazer, Neville Thomas Bonner (1922-1999) was a man of faith and a great healer. Long before “reconciliation” entered the popular lexicon, he devoted his life work to promoting harmony between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

Neville Bonner was born on Ukerebagh Island in the far north of New South Wales on 28 March 1922. Receiving only one formal year of schooling in Queensland, Bonner tried his hand at various jobs as a ring-barker, canecutter and drover. Exuding an entrepreneurial flair, Bonner even started his own Boomerang-making business, “Bonnerang”.

While working in the Northern Rivers region of NSW, Bonner became aware that the surrounding farming community enjoyed a regular breakfast of porridge and sugar. Deciding to enjoy the same local fare one morning, he approached a farmer to ask for some milk. Bonner recalled hitting the ground literally as the farmer screamed “He’d need his milk for his pigs, and not for some little black me!”. With such a horrid incident easily capable of inducing lifelong despondency or embitterment, the doughty Jagera man instead believed that the Northern Rivers farmer “planted my little black feet steadfastly on the rocky road leading to Australia’s Senate”.

“I suppose I was a bit of a rebel. I voted against my own party in and out of government on 23 occasions. I didn’t toe the party-line. I was a member of the party…but I was not blindly a member of the party, I had a conscience.”

Devoted to championing the cause of his people, Bonner campaigned actively for the 1967 referendum to include Indigenous Australians in the census before entering parliament to fill a Senate casual vacancy. When Bonner was escorted into the parliamentary chamber to be sworn in as a Senator on 20 August 1971, he heard the voice of his late grandfather, who said: “It’s alright now boy, you are finally in the council of the Australian elders, everything now is going to be alright”.

Embarking on his parliamentary career, Bonner reflected on what he saw as his four responsibilities:

“My first responsibility was to God because I am a Christian; my second responsibility was to my nation because I am an Australian; my third responsibility was to my state because I am a Queenslander, and my fourth responsibility was to the party that I was a part of and who gave me the opportunity to get into parliament; but interwoven through the whole sequence was my almost all-consuming, burning desire to help my own people, the Aboriginal community, to become respected, responsible citizens within the broader Australian community.”

Rising to deliver his maiden speech to the Senate on 8 September 1971, Bonner acknowledged his entrance to the chamber as a “unique event in Australian history” and pledged to serve all Australians. Decrying the historical mistreatment of his own people, the new senator also affirmed that Australia was a “Grand Country” that had “earned an honoured place in the world” through the valour and skill of its people in war and peace.

In his 12 years as a senator from 1971-1983, Bonner championed the ideals of faith, family, enterprise and patriotism. Believing in opportunity and the human dignity of all, Bonner contributed not only to land rights legislation but championed greater Aboriginal participation in education and employment, affirmed the need for our seniors to be cared for with dignity, defended the rights of the unborn child and stood for the sanctity of marriage and family life.

While faithful to the Liberal Party in which he served, Bonner’s first loyalty was always to his own conscience. He once remarked: “I suppose I was a bit of a rebel. I voted against my own party in and out of government on 23 occasions. I didn’t toe the party line. I was a member of the party… but I was not blindly a member of the party; I had a conscience.”

Following his career in politics, Bonner continued to serve his nation as patron of World Vision and Amnesty International, together with a host of local community organisations. Upon the awarding of an Honorary Doctorate by Griffith University in 1993, Bonner revealed much of his inner driving force and vision for the country he loved.

In what was a remarkable Occasional Address, the Indigenous elder statesman told his audience of graduates that “dignity, courage, sensitivity, compassion, loyalty and responsibility… are the ingredients for total maturity, no matter what race, colour or creed”, adding that, for him at least, “a major component was a love of God”. Identifying as a Christian believer, he remarked that “unapologetically, I confirm I’m an old-time religion fellow myself”. In Old Parliament House, one of the artefacts displayed from his boomerang-making days featured the much-loved epithet of Psalm 23, “The Lord is my Shepherd…He Leadeth Me”.

His faith evidently informed his view on the great national theme of Indigenous Reconciliation. For Bonner, “Reconciliation” was not simply a buzzword or even enlightened social policy, but gospel. If a holy God was able to reconcile himself to sinful humanity through the blood of Christ, then it was eminently possible for Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians to be reconciled to each other. In a poignant end to his Griffith University Occasional Address, Bonner impressed this vision on his charges:

My treasured sons and daughters of Australia, this beloved country of ours will flourish in harmony only when you view it through the knowledge that for an enthralling rhapsody to be played successfully on a piano, one has to play the white and black keys together.

On this special anniversary for both our nation and our first Australians, we honour an elder whose contribution to our public life inspires us to seek “a still more excellent way”.

David Furse-Roberts is the author of the just-released book, God & Menzies: The Faith that Shaped a Prime Minister and His Nation

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?