The commune in a Parisian forest that has become a global movement

“By becoming faithful friends with people living with intellectual disability, all our lives are changed.”

As a university student, Eileen Glass wanted to be radical. “It was the ’60s and a time of great social and political change on campus,” she told Eternity.

“We had a vision that we wanted and needed to change the world.”

But it wasn’t a political movement that caught her attention and became her life.

Instead, while on a trip to France, Glass met another traveller who invited her to visit a commune at the edge of a beautiful forest near Paris. It was called L’Arche – which is French for ‘Ark’ – home to a community of people living with disabilities and those who care for them.

“I came upon this community where people weren’t as invested in the political rhetoric [of the day] but were living something that was incredibly challenging,” says Glass.

Glass was so struck by the vision she saw at L’Arche, and through its founder, Catholic philosopher Jean Vanier, that she committed to stay in the commune for a year. That one year turned to two, which then turned into a lifetime of work for L’Arche.

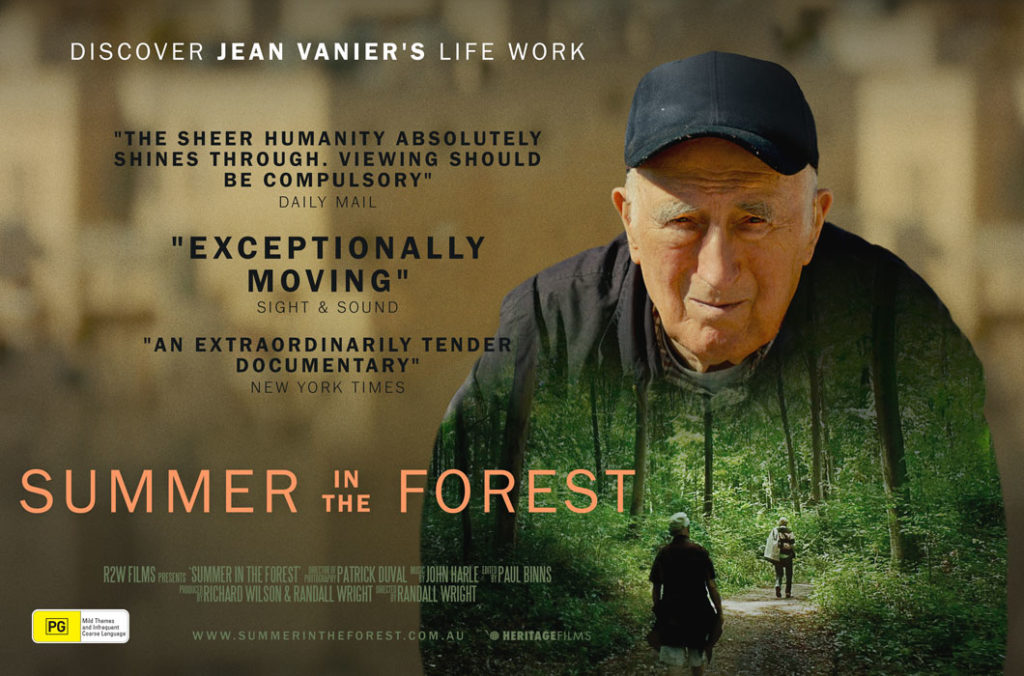

Glass has now been involved in a new documentary called Summer in the Forest that tracks the beginnings of the L’Arche movement. Starting with Vanier and the commune in the French forest. L’Arche extended out to 152 communities across five continents with more than 5000 members.

Glass, who founded the first L’Arche house in Australia in 1978 in Canberra, told Eternity that the documentary is about the experience at the heart of each of the L’Arche communities: “by becoming faithful friends with people living with intellectual disability, all our lives are changed.”

After spending two years at L’Arche in Paris, Glass moved on and spent some time in a newly created L’Arche community in Winnipeg in Canada. Seven of the eight residents with disabilities had come from very large institutions with little experience of living in the world. Having a background in teaching, Glass thought she was entering the house to help the residents discover how to live in an ordinary house on an ordinary street in an ordinary neighbour. But that’s not what happened.

You begin to understand that if the gospel doesn’t speak directly into the lives of those people, it is simply not good news.” – Eileen Glass

“There were times of real difficulty, times of crisis when I was really faced with my limits,” admits Glass. “I began to discover the compassion of the person who lives with intellectual disability towards me. I was no longer the teacher. I was a friend and sometimes I’m functioning better and sometimes I’m the neediest person in the group. Sometimes, my friend who lives with intellectual disability is doing well and sometimes he or she is the neediest person in the group.

“It shaped my understanding of what it is to be human,” says Glass.

“I began to read the scriptures in a new way. I learned to read [them] from the underside, because when you read the gospel alongside people who have known rejection and isolation and exclusion, you begin to read it differently. You begin to understand that if the gospel doesn’t speak directly into the lives of those people, it is simply not good news.”

Glass hopes that Summer in the Forest will challenge people to meet and spend time with people whom the dominant culture tells us are different and, even, lesser. She says the film offers a “fundamental insight” that she has learned herself from living in L’Arche communities: “the person who is weaker, the person that we reject, is in fact the person who is going to heal us when we welcome them into the human family and live in faithful relationship with them.”

Living in a L’Arche community as someone who does not live with intellectual disability, Glass says she quickly learned that the dynamic is not “I am here to do good for you, or to save you.”

“It is: ‘I am here to share my life alongside you, and we’re going to work this out together.'”

“L’Arche offers a level of ongoing friendship.” – Eileen Glass

While L’Arche is grounded in the Christian tradition, begun by the Catholic Jean Vanier, Glass says people of all and no faith are welcome in its communities; they are built on the basis of compassion for the person in greatest need. L’Arche communities look different, depending on their context.

In Australia, the introduction of the National Disability Insurance Scheme has seen a surge of interest in L’Arche communities, with additional funding offering families more choice in housing arrangements. Glass says there is danger is striving for ‘independence’, though, for those living with intellectual disabilities.

“One of the great myths in culture is the myth of independence. We say to people who are vulnerable, ‘we will bring you out of institutional settings so you will have your own home, you’ll live independently and everything will be well’.”

“But we set people up for incredible isolation and loneliness in the name of ‘independence’. The reality is human beings are wired for relationship.

“There’s a recognition that L’Arche offers something more than simply a place to live and a place to be independent. It offers a level of ongoing friendship.”