Thirty years ago the Royal Commission handed down a blueprint to prevent Indigenous deaths in custody

Thirty years ago today, the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody handed down their final report. It included 339 recommendations to address its findings – recommendations aimed at keeping Indigenous people out of custody when it was possible and alive when it was not.

Three decades on, the report remains a compelling and challenging document that provides a vision for a police and prison system in which Indigenous people are not over-represented and are treated with respect and care. And, given that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are the most incarcerated people on earth, the blueprint is one that is desperately needed.

But even a government-commissioned review – a review that was criticised by experts for being too positive – found that only 64 per cent of the recommendations made by the royal commission had been fully implemented. It said 14 per cent were “mostly implemented”, 16 per cent were “partly implemented” and 6 per cent had not been implemented at all.

So what is the situation now and where is Australia still getting it wrong?

Here, Eternity takes a brief look at some of the key issues when it comes Indigenous deaths in custody: establishing the facts; analysing Indigenous deaths in context; causes of death; the offences that lead to custody; and Indigenous deaths as a proportion of the population.

Where can you find the facts about Indigenous deaths in custody?

Recommendation 41 of the report was that “statistics and other information on Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal deaths in prison, police custody and juvenile detention centres, and related matters, be monitored nationally on an ongoing basis”.

The official source of information about Indigenous deaths in custody are the reports released by the Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC), based on data collected through the institute’s National Deaths in Custody Program (NDICP) that launched in 1992 in response to the royal commission’s recommendation.

Collecting, processing and validating the data – both for Indigenous and non-Indigenous deaths in custody to allow for comparison – takes a long time, with verified information about a death in custody becoming available often a year or more after the death itself. Despite the recommendation to publish annual data, the AIC was publishing on a two-year cycle until recently.

The reality of this timeline means that often the facts about an Indigenous death in custody can’t be easily verified by media until years after the death has taken place. Indigenous deaths in custody are therefore less likely to gain the attention of mainstream news.

But in 2018, the AIC decided to begin releasing reports on a single financial year annually. Its most recent release was in December 2020, providing data and analyses relating to deaths in custody during the 2018-2019 financial year.

The AIC’s decision to report more frequently was almost certainly prompted by the actions of the Guardian newspaper in Australia.

In August 2018, finding a “gap in public knowledge” about Indigenous deaths in custody, launched their own Deaths Inside database tracking “every known Indigenous death in custody in Australia from 2008 to 2021” and organising the information per calendar year in an accessible format for readers.

Relying on “publicly available information, such as coronial inquest findings, media reports, and press releases from police and corrective services” plus added details sourced from families (about who, why and how), the Guardian’s database includes more up-to-date information.

But, the Guardian acknowledges, their “real time” database has its own limitation because not all information relating to Indigenous deaths in custody is publicly available. The Guardian explains:

“… there are some years where our data is lower than that compiled by the AIC, because we were unable to find information about cases. Most jurisdictions do not have a complete archive of coronial findings online. In Western Australia, for example, full findings are only available from 2012 onwards.

“Deaths that occurred in recent years may not be listed in the database if there has not yet been an inquest and there was no media reporting at the time, as government agencies do not always publicly report on deaths.”

The AIC’s official statement on Deaths Inside states that it “does not support the concept of ‘real-time’ reporting as this would not allow for the validation and cross-checking of data required to produce a robust and statistically accurate report.” (Access “Official Statements” here).

One key difference between these two data sources is that the Guardian does not track non-Indigenous deaths in custody, so comparing the rates of Indigenous deaths in custody with non-Indigenous deaths in custody – an essential step in pinpointing the different experiences of the two groups so as to identify if and when systemic racism is a factor – still requires accessing the AIC’s data. And of course, that data only becomes available a good year or so after the close of the financial year after the death occurred.

And there’s another important difference between the Guardian and the AIC: who they consider to have died in custody.

The AIC’s data is collected for all deaths that fit the royal commission’s definition of a person who has died in custody. This includes people who have been held in the physical or legal custody of a prison, a youth detention centre, or of police at the time of their death; have died as the result of traumatic injuries sustained or lack of sufficient care provided while in custody, even if that period of custody has now ended; are fatally injured in the process of attempts by police or prison officers to detain them; or are fatally injured while trying to escape police, prison, or youth detention custody.

The Guardian’s database includes all deaths matching that criteria that they have access to, but say they have “also included deaths that occurred in the presence of police officers, including from self-inflicted injuries, and deaths that occurred soon after a police pursuit had been called off, if it’s believed the behaviour of people involved may have been influenced by the presence of police. In this way, we may include deaths that the AIC does not.”

What are the current numbers of Indigenous deaths in custody?

So what are the current statistics for Indigenous deaths in custody?

“The first time we published, in August 2018, an exclusive analysis of 10 years of coronial data found 407 Indigenous people had died in police or prison custody since the end of the royal commission in 1991. In 2019, that figure had increased to 424. Today, it stands at 474,” the Guardian reports.

“The figure of 474 deaths since the royal commission is based on Guardian Australia’s figures for deaths since June 2019 combined with the AIC’s most recent figures, which cover 1991-92 to 2018-19.”

The value of their real time approach to collating these statistics is also apparent:

“At least five of those deaths have happened since the beginning of March this year,” write co-authors Lorena Allam, Calla Wahlquist, Nick Evershed and Miles Herbert. “In 2019, four Aboriginal people were shot dead by custodial officers – the highest number of fatal custodial shootings involving Indigenous people since official reporting of such shooting incidents began in 1991. In three of these cases, criminal trials are under way.”

And, unlike the tables and reports compiled for government by official sources, a few easy clicks into the Deaths Inside quickly provides the details of some of the more high profile cases of recent years are quickly accessed.

Just one of these is Yorta Yorta woman Tanya Day who died on 22 December 2017, 17 days after falling and hitting her head in the cells of Castlemaine police station. Day had been arrested for public drunkenness – a crime that the royal commission recommended be abolished (Recommendation 79).

The format – with a photo and the brief details about her case – reminds the reader that Tanya Day was a real person, not just a statistic.

Day’s case made headlines in 2017 when Australians learned that, after her fall, she was left fatally injured on a floor for three hours.

The coroner investigating her death referred the case to the director of public prosecutions, saying that her treatment at the hands of police officers was “clearly preventable” and that “an indictable offence may have been committed”. The coroner also found that the train conductor who called the police when he saw Day asleep and apparently intoxicated on a train to Melbourne had been biased against her because of her Aboriginality.

Ultimately, Victoria Police said prosecutors had advised against laying charges related to her death and no further explanation was given, prompting protest rallies across the country. Day’s death prompted the Victorian government to promise to abolish the crime of public drunkenness, which it did in February this year.

The Guardian marks Day’s case with a note about the “issues” it raises: “Medical care required but not all given, procedures not all followed, injured in custody.”

Comparing information about Indigenous deaths in custody with non-Indigenous deaths in custody

As important as it is to view Day’s case individually and personally, so is it important to understand it in the wider context of both Indigenous deaths in custody, and all deaths in custody.

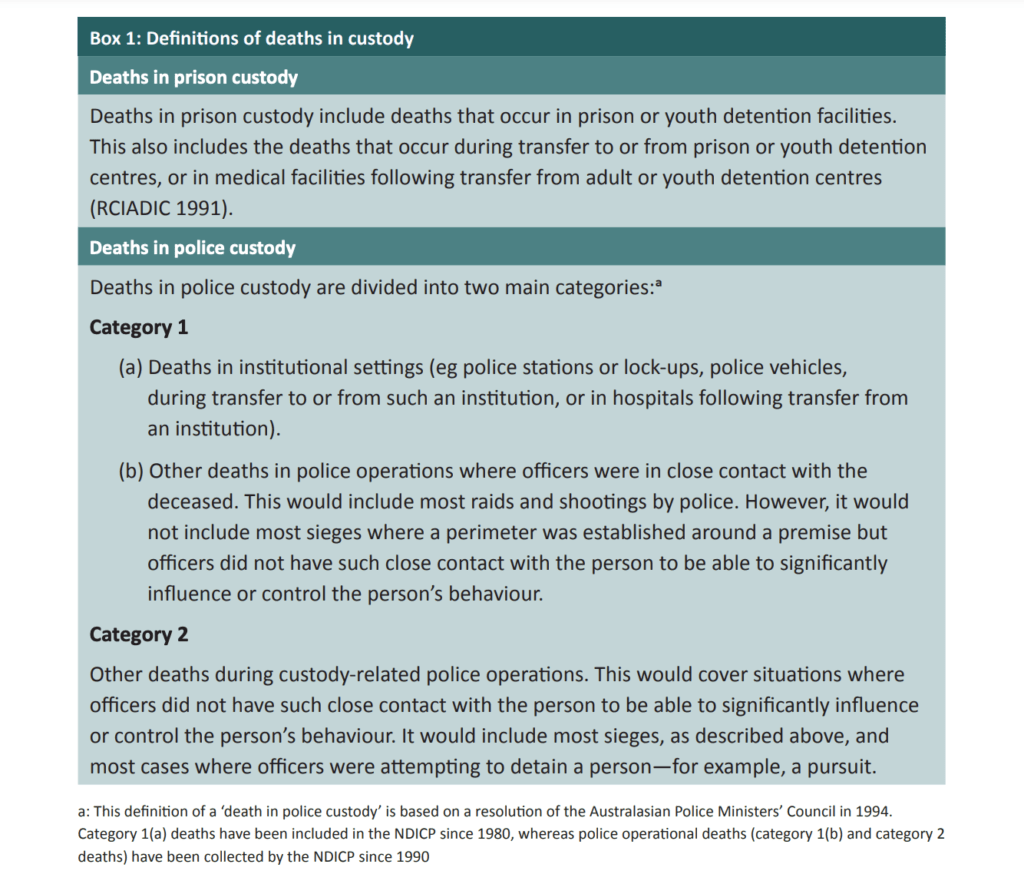

Here the AIC’s reports are invaluable – although easy to misread, with “Deaths in prison custody” defined differently to “deaths in police custody” (which are also divided into two categories – category 1 consisting of two sub-groups). (See table).

“In the 28 years since the RCIADIC (1991), there have been 295 Indigenous deaths in prison custody” reads the AIC report on page 4.

And then on page 13:

“In the 28 years since the RCIADIC (1991), there have been 156 Indigenous deaths in police custody and custody-related operations.”

That takes us to 451 Indigenous deaths at the close of the 2018/2019 financial year.

As a proportion of all deaths in custody, the AIC reports:

“Since 1989–90, Indigenous persons have comprised 20 percent (n=168) of deaths in police custody,” the AIC reports (page 13).

At a first look, Indigenous deaths in prison custody appear to be in line with non-Indigenous deaths in prison.

The report explains that in 2018/2019, there were 89 deaths in prison custody in total, 16 of them Indigenous (18 per cent).

“The death rate of Indigenous prisoners was lower than the death rate of non-Indigenous prisoners nationally (0.13 and 0.23 per 100 respectively), and in all jurisdictions except for Victoria (0.24 vs 0.23 per 100 prisoners) and the Northern Territory (0.21 vs 0.00 per 100 prisoners”.

The situation is significantly worse for Indigenous people who die in police custody with the report noting, “of the 24 deaths occurring in police custody in 2018–19, four were of Indigenous persons and 19 were of non-Indigenous persons”.

That means “the death rate of Indigenous persons in police custody was 0.61 per 100,000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population aged 10 years and over. The death rate of non-Indigenous persons in police custody was 0.09 per 100,000 non-Indigenous population aged 10 years and over.” (page 12). This Indigenous death rate is more than 6 times the rate of non-Indigenous people.

That means Indigenous people who are in police custody but who have not been placed in prison – i.e. have not been charged and convicted – are dying at a significantly higher rate than non-Indigenous people who are in police custody but not in prison.

In the reports’ Appendix tables, it is clear that Indigenous death rates in police custody have remained consistently high since the AIS began tracking them in 1980, despite the fact that “police operational deaths (category 1(b) and category 2 deaths) have only been collected by the NDICP since 1990.”

Here, Indigenous deaths in police custody since 1980 total 230, with 8 more in youth justice. In comparison, non-Indigenous deaths in police custody total 831 and in youth justice total 10. (pages 36-38)

Cause of death

The AIC’s report also compares the causes of death for Indigenous deaths in police custody and non-Indigenous deaths in police custody – highlighting the gap in health experienced by the two groups.

“Since 1989–90, the greatest proportion of Indigenous deaths in police custody have been attributable to external trauma (33%, n=55), followed by natural causes (22%, n=36) and head injuries (14%, n=24). In comparison, most non-Indigenous deaths in police custody have been attributable to gunshot wounds (36%, n=243) or external trauma (31%, n=208).” (Page 14)

For 2018/2019, the report states:

“The rate of natural cause deaths was higher for non-Indigenous prisoners than Indigenous prisoners (0.13 vs 0.09 per 100). The specific cause of death was known in 10 of the 11 Indigenous deaths that were attributable to natural causes. Three of these deaths were from heart disease or related ailments, two were from cancer, two were from respiratory conditions and one was from each of infectious diseases, other conditions and multiple conditions. Of the 29 non Indigenous natural cause deaths where the specific cause of death was recorded, most (52%, n=15) were from cancer, followed by respiratory conditions (21%, n=6) and heart disease or related ailments (14%, n=4).” (page 6)

This author is hesitant to draw conclusions here, in an area outside her field of expertise.

However, these sets of data may be seen to indicate that Indigenous people who are taken into custody are not being given the medical treatment they require to stay alive, either after receiving external injuries, or to manage existing health conditions, or when both issues are combined – a concern that has been raised in several high profile cases of Indigenous deaths in custody, including that of Anzac Sullivan, Nathan Reynolds, Danny Whitton and Ms Dhu.

Comparing MSOs – Most Serious Offence leading to custody

The NDICP also collects information on the most serious offence (MSO) leading to custody, grouping offences into six categories: violent, theft-related, drug-related, traffic, good order and other/unknown (in order from most to least serious).

“Since 1989–90, Indigenous persons who died in police custody have most commonly been suspected of having committed a theft-related MSO (33%, n=53) or a good order offence (24%, n=39). Over the same time period, non-Indigenous persons have most commonly been suspected of committing a violent offence (38%, n=255), or a theft-related offence (17%, n=113). pg 15

So, when Indigenous people who die in custody 33 per cent of the time the reason they are in police custody is that they are suspected of theft (which includes break and enter, other theft, property damage and fraud). 24 per cent of the time, they are in custody for “a good order offence”, which is the lowest category of offences which includes includes public drunkenness, justice procedure offences, breaches of sentencing like defaulting on a fine, prostitution, betting and gambling, disorderly conduct, vagrancy and offensive behaviour.

For a non-Indigenous person, 38 per cent of the time the reason they were placed in police custody was because they were suspected of a violent crime, which includes homicide, assault, sex offences, other offences against the person and robbery. 17 per cent of the time it was due to suspicion of theft.

Comparing rates of Indigenous people in custody with non Indigenous people in custody

But the most important context for all of this is simply the number of Indigenous people who are taken into custody, given what a small percentage of the population Indigenous people are.

This is something the AIC notes clearly (albeit when discussing the rates of Indigenous people in prison custody, not in police custody which would reflect even more poorly on the Australian government) – acknowledging that the very same problem was emphasised by the royal commision, thirty years ago.

“In 1991, the RCIADIC concluded that Indigenous persons were no more likely to die in custody than non-Indigenous persons, but were significantly more likely to be arrested and imprisoned. The same remains true today,” it reads.

“The most recent Australian census found that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders comprise three percent of the Australian population (ABS 2017). In comparison, Indigenous prisoners made up 28 percent (n=11,866) of the Australian prisoner population at 30 June 2019 (ABS 2019b).

“Further, the Indigenous imprisonment rate was 12 times the rate for non-Indigenous prisoners in 2019, and has increased by 35 percent since 2009, compared to an increase of 26 percent for non-Indigenous prisoners (ABS 2019b).”

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?