How resolutions can help in spiritual transformation

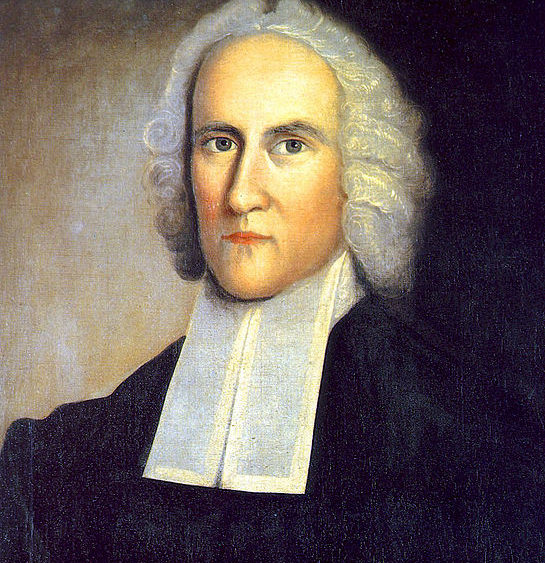

Self-examination was a roadmap of life for American theologian Jonathan Edwards

“Resolved, to ask myself at the end of every day, week, month and year, wherein I could possibly in any respect have done better.” (Jonathan Edwards, January 1723)

They may not last, but that is not quite the point. At this time of year, many of us turn to New Year’s Resolutions as a way of harnessing the lessons of the year past and preparing better versions of ourselves for the year ahead.

Cutting out smoking and drinking are frequent aspirations. Perhaps actually turning up at the gym or spending quality time with friends rather than at the office feature in the list. Personal happiness or financial gain may lie behind our decisions.

Praying more or reading the Bible more are standard Christian solutions to any aspirational goals, for they are easily measured and have an aura of godliness about them, but like many other resolutions they focus on means not ends. At this time of year, we frequently resolve to change superficial behaviours, but less often on the agenda that is going deeper to refocus our heart. Can resolutions play any role in spiritual transformation?

At this time of year, we frequently resolve to change superficial behaviours, but less often on the agenda that is going deeper to refocus our heart.

American revivalist preacher, philosopher and theologian Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758) thought so. He was keen to pursue spiritual growth, so as a youth (1721-23) he wrote 70 resolutions as a way of guiding his path towards Christian maturity. His primary strategy was self-examination, trying to find patterns in his behaviour, which he could pick apart to get to the bottom of his slackness or disobedience, and replace with new actions or attitudes.

But this wasn’t Edwards’s practice alone. Similar resolutions were drafted by many leading thinkers of his day as a turn towards discipline or devotion. English cleric and theologian John Wesley loved to interrogate his soul methodically, and US statesmen Benjamin Franklin and George Washington drafted resolutions too.

Edwards wrote resolutions for he knew that growth, as a human being and as a Christian, takes energy.

However, Edwards’s rigorous survey of spiritual progress was longer than most lists written even by the Apostle Paul: he would repent of “whatever is not most agreeable to a good, and universally sweet and benevolent, quiet, peaceable, contented, easy, compassionate, generous, humble, meek, modest, submissive, obliging, diligent and industrious, charitable, even, patient, moderate, forgiving, sincere temper.”

Edwards wrote resolutions for he knew that growth, as a human being and as a Christian, takes energy. His motto was never “let go and let God!” He wanted to make the most of the time he had in this world and aimed high, so he resolved “to act just as I would do, if I strove with all my might to be that one [complete Christian] who should live in my time.”

There is a difference between earning God’s mercy and exerting effort to grow in grace, so his resolutions were prefaced by the reminder that any maturity would come as a result of relying on the grace of God. He wrote elsewhere: “Religion is sweeter, and what is gained by labor, is abundantly more precious: as a woman loves her child the better for having brought it forth with travail.”

He was setting out on a spiritual journey, and he needed some kind of map.

Too often we just assume that growth will happen without our active engagement. Like Edwards, we should make a plan for our own spiritual growth in the year ahead!

But something else is happening when Edwards wrote resolutions. He was a precocious youth who was trying to emerge from the shadow of his family’s faith, and resolutions helped him to stand on his own two feet, and to stand up to the pressures of his Puritan theological world.

He was trying to find himself. He was learning that conversion is just the beginning of Christian experience. He was setting out on a spiritual journey, and he needed some kind of map to help him reach his destination.

Like Edwards, we should make a plan for our own spiritual growth in the year ahead!

We can perhaps recount a wonderful experience of conversion, but Edwards teaches us not to rest on this experience alone. The whole of life is learning how to pursue God’s wise ways in the world. Edwards’s Enlightenment world prized rationality or emotions without reference to God, but he made it a priority to nurture his soul, where every part of his life was joined together. His intense youthful spirituality shows us his deep desire to integrate every part of his experience in order to find lasting satisfaction in God. In a world of fleeting pleasures, let’s make sure that we don’t neglect our heart of hearts, so that we can savour God’s promises, presence and purpose in 2019.

In a world of fleeting pleasures, let’s make sure that we don’t neglect our heart of hearts.

But there was something very different about Edwards’s resolutions: when he wrote them, the first day of the year was March 25, and Puritans didn’t celebrate festivals such as the first day of January anyway. Primary importance was attached to Sundays which are more likely to keep us spiritually accountable for they come around more often! Indeed, after graduating from university, he gave up writing resolutions altogether. New Year resolutions may prove useful, but in the end regular means of grace such as sermons and sacraments are God’s chief strategy for providing assurance and directing our path towards heaven.

Rev’d Canon Dr Rhys Bezzant is a lecturer at Ridley College in Melbourne and director of the Jonathan Edwards Center Australia.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?