The virgin stripped bare

A review of The Testament of Mary by Colm Toibin, Sydney Theatre Company, Wharf 1, until 25 February

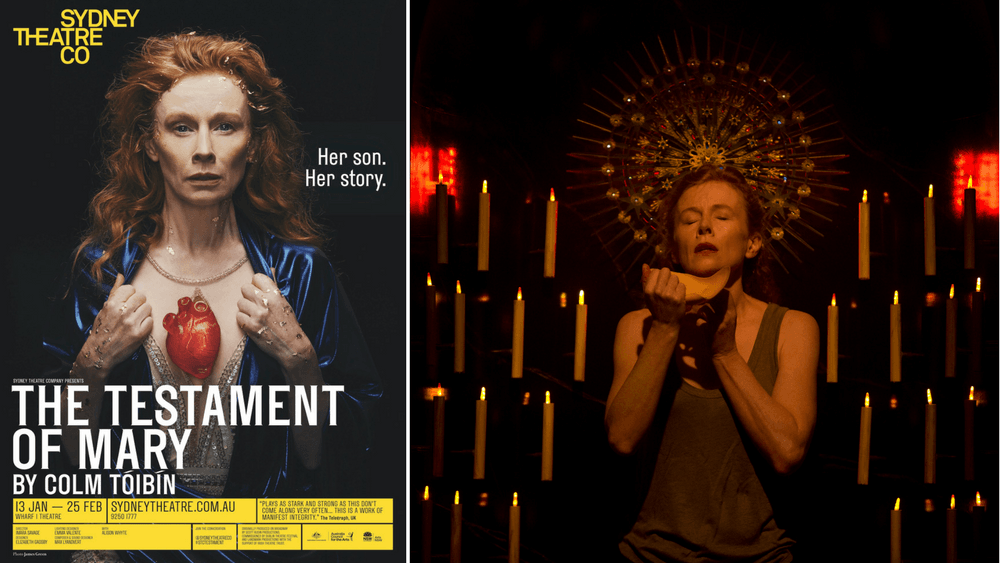

Mary stands in an arched alcove, her flowing Botticelli hair and sumptuous robes glowing in the candlelight. On her chest, as if broken, are a red heart and a right breast.

Bit by bit the Catholic world’s most revered icon is dismantled. The robes come off, the false heart and breast taken off. Finally Mary pulls off her wig and reaches up to peel off her mask.

The opening image of The Testament of Mary is a stroke of genius. Here is the Virgin Mary, the icon of icons, unmasked.

For the next hour and twenty minutes, the fragile figure played by Alison Whyte prowls the stage in basic singlet and track pants. As the play by acclaimed Irish writer Colm Toibin begins, his Mary is holed up in a house in Ephesus being questioned and cared for by two disciples. They want her to be a witness to her son’s redeeming work on the cross but she is defiant. She is a mother and a widow who is trying to come to terms with what has happened to her son. This Mary is the antithesis of the godly woman we know from the Bible. As she recounts her version of the events of Jesus ministry she does not deny his miracles but seems indifferent to them. She is agnostic. She doesn’t understand anything beyond her realm.

The author, who calls himself “a collapsed Catholic”, has created a mythic figure who cannot see her son’s death as anything other than a Greek tragedy.

Christians need not avoid this play. Taken on its own terms, as the heartbreaking story of a mother who does not understand her son’s mission but is racked by grief for a fate she could not protect him from, it is very moving. The imagery is raw and powerful. It is fascinating to imagine Mary’s feelings as she witnessed her son’s crucifixion. Here it is laid bare in eviscerating detail. Mary is haunted by having fled from the scene before Jesus died. She was not able to hold him and prepare his body for burial. The cruelty of the experience is underlined by an extraneous anecdote of a man feeding rabbits to a bird of prey.

Alison Whyte, best known for her role on the Australian television series Frontline and Satisfaction, is spellbinding in the role. Her inner anguish is wrought in the sinews of her lean body as she obsesses over her fears and failures and lapses in judgment. She tries to take Jesus away after the wedding at Cana, where he turns water into wine, and hide him for his own safety. She is frightened when he calls himself the Son of God. She misses the needy boy he used to be and does not understand his confidence and radiance.

But even Christians can find it useful to speculate on how a mother would cope with the contradiction of having raised a dependent child who was now full of the power of God.

This play began as a monologue then became a novella before Toibin wrote the dramatisation. I read the novella before seeing the play and found it helpful to understand the twisted, revisionist theology before seeing it dramatised. The central conceit reminded me of CS Lewis’s “liar, lunatic or Lord” conundrum, with his mother favouring the second description, but in fact it is she who has been unhinged.

The author, who calls himself “a collapsed Catholic”, has created a mythic figure who cannot see her son’s death as anything other than a Greek tragedy.

But even Christians can find it useful to speculate on how a mother would cope with the contradiction of having raised a dependent child who was now full of the power of God. And how the wonder and danger that Jesus stirred up affected his mother.

For me, one of the most fascinating speculations involves the story of Lazarus: after Jesus raises him from the dead Mary is bursting to ask him what he could reveal about the next world from his four days in the grave. But the moment passes and Lazarus is led away by his sisters.

In this version, unhappily, resurrecting Lazarus is portrayed as a curse. The aura of death still hovers around Lazarus and he has to lie in a darkened room and be fed softened bread.

Still, it is fascinating to imagine how people would have reacted to Lazarus after his raising and how he lived the rest of his life.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?