Amid these despairing times, this Tuesday marks the bicentenary of the birth of a remarkable Christian hymn writer whose own life-story, despite many hardships, was one of irrepressible hope.

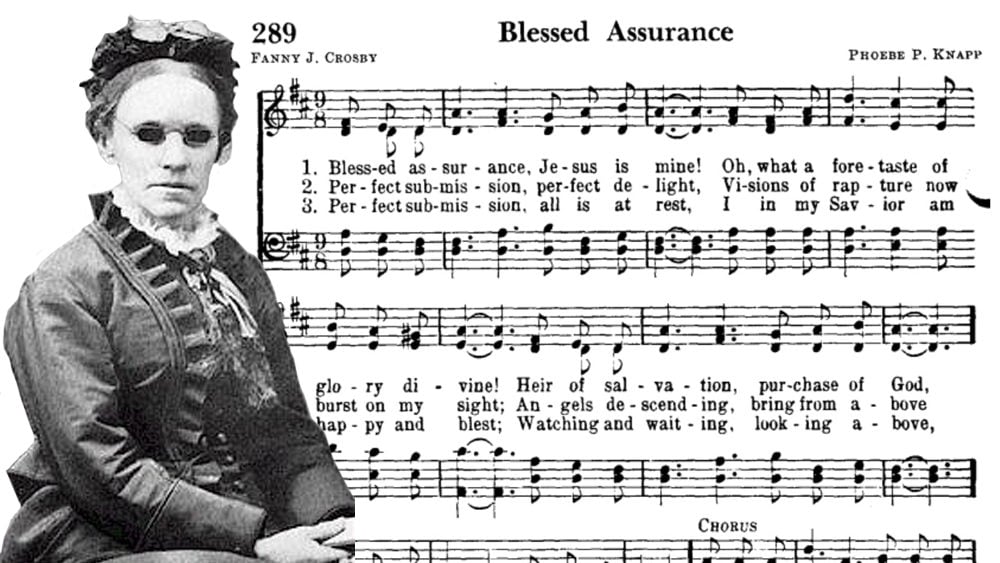

The hymn writer was America’s Fanny Crosby whose immortal songs of “Blessed Assurance”, “To God Be the Glory” and “All the Way My Saviour Leads Me” became the soundtrack of the Billy Graham Crusades, and indeed, much of evangelical worship since the Victorian age.

https://vimeo.com/152338900

Despite suffering blindness since early infancy, this “Queen of Gospel Song Writers” penned some 9000 hymns. In a lifetime that spanned every US President from the death of John Adams to the birth of Ronald Reagan, she championed education for the blind, campaigned against slavery, and dedicated her latter life to rescue mission work, bringing the hope of Christ to alcoholics, the homeless and the unemployed in the slums of Manhattan.

Born in the village of Brewster, New York, on 24 March 1820, Frances Jane Crosby was heir to the rich Puritan tradition of the American northeast. Its Calvinist values of total dependence upon God, moral integrity, frugality and self-discipline defined her lifelong work and ministry.

Blindness was “the greatest blessing the Creator ever bestowed on me.” – Fanny Crosby

As her biographer, Edith Blumhofer observed, “She boasted a family line that valued the ‘stuff’ of fabled Yankee pride – independence, sobriety, thrift, morality, hard work, public service, family loyalty, unashamed patriotism, and above all, devotion to duty.”

Crosby’s early life was marked by personal tragedy. At just six weeks old, she lost her sight, but instead of cursing this loss, she remarked that it was “the greatest blessing the Creator ever bestowed on me.”

For Crosby, the blindness she experienced in this temporary life gave her the hope that the first vision she would have in the life to come would be that of Christ her saviour.

Losing her father at just six months, she was raised by her mother and maternal grandmother who grounded her in Christian principles and helped her memorise long passages of the Bible. Drawing on her remarkable memory, she had ready inspiration for penning thousands of her hymns.

Educated at the New York Institution for the Blind, she excelled academically in English literature, science, philosophy and music, mastering the piano, organ, harp and guitar. Crosby remained at this Institution as a student and then a teacher for 23 years.

In this capacity, she emerged as a vocal advocate for the education of the blind and in 1846, she became the first woman to speak in the United States Senate. Shortly afterwards, she addressed a joint session of the United States Congress to advocate support for the education of the blind in Boston, Philadelphia and New York.

While raised a Christian, Crosby actively dedicated her life to Christ in 1850 when she knelt before the altar in New York’s Broadway Tabernacle. Later, she joined the Sixth Avenue Bible Baptist Church in Brooklyn, where she served as an urban missionary, deaconess and lay preacher in conjunction with her prolific output of hymns.

A fellow-traveller of the Wesleyan holiness movement, her hymns frequently celebrated the new birth to be found in Christ and the beauty of living a life dedicated to the service of God. Working closely with the evangelical revivalists, Dwight L Moody and Ira D Sankey, Crosby helped birth the “gospel hymn” of popular music set to popular verse.

In addition to her gospel ministry in deed and song, Crosby was a patriot who cared deeply about the moral wellbeing of her country and its people. Accordingly, she acquitted herself to national causes she saw as righteous and just. With slavery part of her early childhood, she became a lifelong abolitionist and this propelled her to support the anti-slavery Whigs, and eventually, Abraham Lincoln’s new Republican Party. Devoted to the Union in the American Civil War, Crosby composed multiple anthems and ballads rallying her compatriots to fight for liberty and the abolition of slavery.

Her prolific hymn-writing put many of the Bible’s words to song.

In 1858, Crosby married Alexander van Alstyne, a fellow teacher whom she had met in 1843. At his insistence, Crosby retained her maiden name. After settling in a rural village outside New York, Alexander and Fanny had a daughter in 1859 who died in her sleep shortly after birth. Naturally distraught, Crosby wrote, “God gave us a tender babe but the angels came down and took our infant up to God and to his throne”. It is believed that this inspired her to write the much-loved hymn, “Safe in the Arms of Jesus”.

Continuing her hymn writing, rescue mission work and public speaking engagements until her final days, Crosby died at Bridgeport, Connecticut, in February 1915 just short of her 95th birthday.

In her life’s work, Crosby personified what historian David Bebbington identified as the fourfold synthesis of evangelical Christianity. Her prolific hymn-writing put many of the Bible’s words to song. The focal message of her hymns was the atoning work of Christ on the cross. Her ministry in both deed and song was impelled by the belief that people needed to be converted, and finally, her activism expressed itself in her rescue mission work and public advocacy for the blind, the poor and the captive.

The bicentenary of Fanny Jane Crosby’s birth is a timely opportunity to celebrate not only her enduring gift of gospel song favourites, but her living example of hope in the gospel of new life.

David Furse-Roberts is an Adjunct Research Fellow at the Australian Centre of Christianity and Culture at Charles Sturt University Canberra and the author of The Making of an Evangelical Tory: Lord Shaftesbury and the Evolving Character of Victorian Evangelicalism.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?