"Weird Christians" is a new movement that likes old stuff

But aren’t we all weird?

When you hear that there’s a new movement called “Weird Christianity,” most believers will respond “Aren’t WE the weird ones?”

True. Most Christians know that neighbours and people at work might think of us as “weird” – or worse.

“What we have in common is that we see a return to old-school forms of worship …” – Tara Isabella Burton

But a group of young US Christians have captured media attention as a movement of self-proclaimed “Weird Christians”. Weird because they pursue older ways of being Christians: formal services following a written “liturgy”, even the Latin mass, incense, and chants or sung services.

“Many of us call ourselves ‘Weird Christians,’ albeit partly in jest,” Tara Isabella Burton wrote in The New York Times.

“What we have in common is that we see a return to old-school forms of worship as a way of escaping from the crisis of modernity and the liberal-capitalist faith in individualism.”

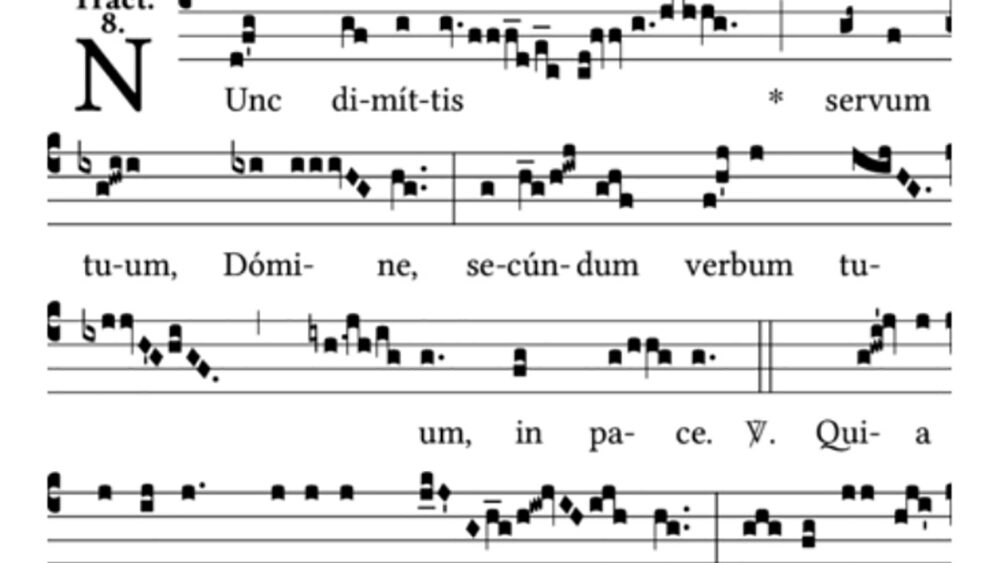

Locked down and choir-less, her church in New York had the organist lead them in Gregorian chant – a form of plainsong, the unaccompanied music of the medieval church. “This was just one of many remote religious activities I’ve participated in recently,” wrote Burton.

“I have also, for example, gathered over Zoom with friends for compline, a nighttime prayer with roots in the medieval monastic tradition. And I’m not alone. One friend has been dialling into Latin Masses at churches across the United States: a Washington Mass at 11am; a Chicago one at noon.

“The coronavirus has led many people to seek solace from and engage more seriously with religion. But these particular expressions of faith, with their anachronistic language and sense of historical pageantry, are part of a wider trend, one that predates the pandemic, and yet which this crisis makes all the clearer.”

Seeking something different

Andrew West interviewed Burton for the ABC’s Religion and Ethics report, where she made the point that her group sees a lot of Christianity as too normal, too close to the American mainstream. Just too seeker sensitive. The “Weird Christians” want something different from the consumer culture that surrounds them. So they seek something different. This includes desiring something old rather than new.

In particular they seek liturgy (customs or a formula of public worship often written in some sort of prayer book), that are regarded in many churches as anachronistic.

Andrew West himself represents something of what the weird-seekers want. “I call myself a liturgical Anglican or, more concretely, a prayer book, hymns, altar and vestments Anglican – all the things that were once staples of suburban Anglicanism in Sydney until the mid-1980s when I was confirmed.”

“I know anecdotally that true Anglo-Catholic parishes are pretty healthy: Christ Church Saint Laurence [Sydney]: St Peter’s, Eastern Hill in Melbourne; Christ Church, South Yarra. I’ve also heard St John’s, Gordon and St Paul’s in Burwood, which we attend [in Sydney], is doing pretty well.

“I wonder if this is because they’ve scooped up ‘refugees’ from other parishes that have slipped down the candle, as it were.”

West, like some other Anglicans, deplores the decline in use of the written Liturgy from evangelical Anglican churches in Australia. Glen O’Brien a University of Divinity Associate Professor contributes a history of the Methodist Prayer book in “When We Pray” a new book about liturgy on Australia – noting the decline in the use of the old Methodist Book and Uniting in Worship – the Uniting Church version. He quotes D’Arcy Wood (a former UCA president) as noting in 1996 that the “peoples book’ (the pewsitter’s book) was only used by 20 per cent of congregations.

The past already points to our future

Australia’s most unusual Baptist Church at South Yarra, Melbourne, holds prayer-book-style liturgical services. Their minister Nathan Nettleton is somewhat skeptical of the “Weird Christianity” movement. “The phenomena described in the article seems to be marked by a great nostalgia for a perceived ‘golden age’ in the past, with its longing for gothic architecture and it’s turning to things like the Latin Tridentine rite,” he tells Eternity. Rather he sees “SYCBaps” as early adopters of a broader “ancient-future” movement.

“Rather than thinking the answers are to be found in replicating ancient ways, we think that the ancient ways can provide signposts that will help us find our way to new answers for the future,” explains Nettleton. “We look at the ways the early Church engaged with their context, and ask how might that guide us in engaging meaningfully with the context that we face now.

“Although SYCBaps uses a structured written liturgy that has patterns going back to the early centuries, many of the written prayers within that structure are very modern and very local. And certainly not in Latin.”

In fairness to the “Weird Christians” in the US, there is overlap. The Tridentine enthusiasts are only a small part of the weird contingent. Many liturgical (or weird) Christians blend various traditional and modern elements in their services. There are theological conservatives and liberals using blended services – in the US, both The Episcopal Church (TEC) and the Breakaway Anglican church of North America (which split over TEC adopting gay marriage) have ancient-future services.

In Australia, the Anglo-Catholic movement – once one of the most powerful movements in the country – is still in decline. The Anglican Dioceses (regions) which use formal liturgy are the most in decline.

“Wesley’s hymns allowed Methodists to do more efficiently what all evangelicals desired …” Piggin and Linder

But possibly the most powerful “liturgy” ever in Australia – in terms of church growth – belonged to the Methodists. “Our true liturgy, our doctrinal standard” is how they spoke of the “Methodist Hymnal,” as recorded in Stuart Piggin and Robert D. Linder’s “The Fountain of Public Prosperity”.

“Wesley’s hymns allowed Methodists to do more efficiently what all evangelicals desired, to experience God in a personal and individual way and to express that experience corporately through music.”

That church grew fast. In 1870, ten per cent of the Victorian population was in Wesleyan services once a week, and 26.2 per cent of South Australians described themselves as Methodists in 1901.

Nathan Nettleton makes the point that every church has a liturgy, whatever it is called. As an example, he points to the structure of Hillsong services and, in particular, seeing echoes of older practice in the prayers.

Taking note of the existing diversity of unwritten liturgies is raised by Amelia Koh Butler, Interfaith chaplain at the Western Sydney University in a chapter of When We pray. She uses the examples of Pacific Islander church customs as examples of locally grounded worship.

For the moment in Australia, the growing liturgy is Pentecostal worship – just as hymns were an engine of Methodism in the Victorian age.

What the world thinks weird

“Weird” may simply be another code word for Christianity rejecting what the world thinks, and being consciously different.

Mike Frost from Baptist Morling College (Sydney and Perth), says: “In fact, it could be argued that the church is at its best when it throws off its desire for acceptance and conventionality and launches into the strangest and most counter-cultural behaviour.”

He points to a slightly different set of weirdness including the Irish monks who re-Christenised Western Europe, and the monks who kept the flickering flame of Christianity alive in a period of nominal Christianity in the Holy Roman Empire. He also nods to the radical Anabaptists (Mike is a Baptist, after all) who thought the Reformation had not gone far enough – and to Pentecostals who are committed to counter-cultural holiness.

“The Celts were weird because of their outlandish missionary bravery, the Cistercians for their asceticism, the Anabaptists for their non-conformism, the Pentecostals for their boisterous spirituality,” Frost writes. “And all of them were viewed suspiciously by the staid and culturally acceptable church of their time, and in the Anabaptists’ case, persecuted outright.”

Just how weird to be, and how culturally acceptable the church can be without losing its saltiness is a tension that will be with us until we are in a place where we don’t feel weird at all.

Feedback

Do you think others think you are weird? How do you respond?