What ‘respectful disagreement’ actually looks like

Cornel West and Douglas Murray discuss euthanasia, free speech and gay wedding cakes

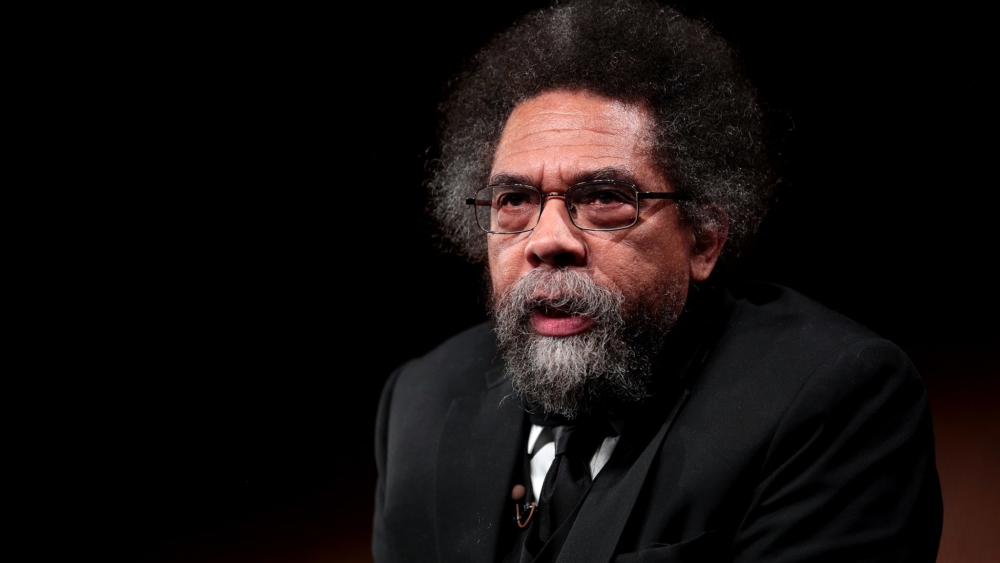

Respectful disagreement was on display again in Australia this week, with charismatic philosopher and activist Dr Cornel West in Sydney for a series of events with English author, journalist and political commentator Douglas Murray called “Polarisation”.

West began his Australian trip with his second appearance on the ABC’s Q&A programme on Monday night. He was seated alongside Liberal senator Eric Abetz, whom he continually referred to as “my brother,” as they disagreed on topic after topic.

Eric Abetz, left, and Cornel West on Q&A

West is the professor of public philosophy at Harvard. He has 45 years of what he calls “standing in solidarity” working with marginalised groups, particularly in the US, from the civil rights movement to joining Native Americans’ pipeline protests at Standing Rock. And when he speaks, he employs the tools of his tradition with a mastery reminiscent of Martin Luther King Jr.

So when West calls someone a “brother” or “sister” – even on Australian public television, as he did on Monday night – it seems perfectly natural. When those who don’t share West’s heritage employ the same language, the effect is somewhat different. This was the case when Senator Abetz returned the favour, calling West “my brother”.

The moment wasn’t lost on host Tony Jones, who took the next opportunity to ask West, “And Cornel West, do you agree with your brother, Eric?” – much to the studio audience’s amusement. Yet even more compelling than Jones’s wit was West’s cheerful reply: “No, no. He’s wrong again. He’s wrong again. But the dialogue is important.”

It has been a tough few years for proponents of respectful disagreement in public forums. Conversations on social media platforms have been dominated by heated arguments over US politics and polarising social issues such as same-sex marriage. Fake news has effectively been used to divide groups who have much in common.

There are strong indications that social media users are drawing away from online dialogue forums, with people sharing less content in news feeds (where all their social media friends can see them and comment on them) and sharing more content through messaging and in groups (reducing the number of people who can converse about it).

Earlier this year, Facebook executive Adam Mosseri told Columbia Journalism Review’s Jessica Lessin that the volume of social media content posted to “stories” – another form of sharing social media content that doesn’t make a space for dialogue – is increasing so rapidly that he expected it to eclipse the volume of content posted to news feeds soon.

“Just be candid! Say what you say and mean what you say!” – Cornel West

These days, even when online conversations don’t get nasty, there seems to be a lack of sincere dialogue, with users pretentiously thanking one another for “sharing their thoughts” before reiterating their own opinions in a manner that shows no evidence of having engaged with the opinions expressed by others.

The issue of sincerity came up on Wednesday night, at West and Murray’s Sydney show at the Enmore Theatre. West contrasted “white conservatives who are very candid about their contempt” and “white liberals who might say ‘Oh, those Muslims, you just have to keep track of them today – there’s just too many but, in general and in public, I think they’re nice people.'”

“Just be candid! Say what you say and mean what you say!” West exclaimed, before going on to explain that candour was not the same as offence.

Murray was likewise concerned about insincerity in public conversation. “If we have no way, no means of judging a sincere claim and an insincere claim, now that’s a very big problem to be starting with. It’s like Robert Frost said, it’s like playing tennis with the net down – that’s what he said about free verse. Who’s going to adjudicate in these situations? Particularly if there’s something to gain from insincere claims.”

Like West, Murray is charismatic and likeable and has plenty of fans. He’s well-presented, well-educated and possesses a brilliant mind as well as being evidently kind and compassionate.

“Sometimes now they’re passionate about somebody baking a cake and I think, is that what we’re reduced to?” – Douglas Murray

As a pair they were possibly a little too likeable for some in the audience, who apparently came to see “their guy” intellectually smack down the “other guy”. Some people seemed a little unsure of where to hang their allegiance when no one was being painted as the villain. One attendee was overheard saying, “Why is this called ‘Polarisation’? It should be called ‘United’ or ‘Best of friends!’”

But despite their mutual respect, the evening was not without controversy. There was plenty of disagreement as West, a Christian, and Murray, an atheist, canvassed controversial topics such as affirmative action, identity politics, free speech, Israel and Palestine, and President Donald Trump.

Even the thorny issue of cakes for gay weddings got a mention. “I’m gay but I loathe that version of it,” said Murray. “I think you can advocate for gay rights, advocate for equality without making yourself an interest group … the people who fought for gay rights, sometimes now they’re passionate about somebody baking a cake and I think, is that what we’re reduced to? Is that what we have to be, that you have to crush every baker who just won’t bake gay wedding cakes? I’m not comfortable with that at all.”

In discussing the divisive issue of euthanasia, Murray – who has studied and written about it – raised the “darker bits” involving mental illness. “People had successfully managed to make mental and physical illness have parity,” he said. “They say ‘Well, mental illness is like physical illness, something that completely takes over your life and can destroy it, so perhaps people with no physical illness can apply to have euthanasia’ – and they do it.” He went on to reference a controversial news story out of the Netherlands this week – that of 28-year-old Aurelia Brouwers, who was was allowed to end her life on account of her psychiatric illness.

“I know people who feel like they’re tired of life in their teens – should they therefore have the right to end it?” – Douglas Murray

After a long line of men stood to ask long and self-indulgent questions – despite the host’s instruction to keep them brief and direct – a young woman called Zoe asked Murray to clarify his position on euthanasia. Murray reiterated his opposition, saying he thought it was “the ultimate human tragedy” and lamenting a phrase used in the Netherlands – “tired of life syndrome”.

“I know people who feel like they’re tired of life in their teens – should they therefore have the right to end it? There are groups that say that you should. I cannot agree with that. Who knows in their teens what life has to hold for them and the amazing things they’re going to find? Who in their teens knows what’s facing them? Who in their twenties knows the things that will come from their life and the opportunities?” he said.

When facilitator Dan Illic called for a quick, last question, another female questioner took the microphone and addressed Murray: “I make this comment in relation to Zoe’s question about euthanasia,” she explained.

“When you’re an Aboriginal person, particularly a black woman, it’s easy to look forward to dying in custody from police and correctional brutality in Australia, like that of my brother … who died a year-and-a-half ago in custody, as an Aboriginal death in custody.

“It’s easy to look forward to your life expectancy being cut short by at least twenty years, compared to non-Indigenous people, and it’s easy to look forward to your nieces and nephews taking their lives by suicide, at the highest rate in the world, at ages nine, nine, ten, eleven years old.

“So, what a privileged world you must live in, and I hope to look forward to that one day.”

The young woman was respectful, yet did not couch her statement with the kind of ego-soothing caveats many people would have. She seemed to be confident that her critique was an act of service to him.

To his credit, Douglas Murray did not retreat to the insincerity of “thanking” her for her contribution or the condescension of congratulating her for speaking up. Nor did he make any attempt to deflect attention from the privilege she’d identified, by listing all the hardships he’d experienced.

“We have to be committed to putting a priority on confronting the powerful.” – Cornel West

Instead, Murray silently gave her his full attention as she delivered her unflinching critique, then sat in obvious reflection, appearing to contemplate the realities he’d failed to self-identify, as West expertly brought the evening’s respectful disagreements to a close.

“In the end, even all the wrestling with meaning that is existential, personal and interpersonal, when it comes to structures and institutions, we have to be committed to putting a priority on confronting the powerful, not in any way scapegoating the vulnerable. All human beings must be criticised. We all must be relentless in our criticism,” West said.

“If we are about anything in these dialogues, it’s about a human connection, even given deep disagreements.” – Cornel West

He went on to make a point about the different philosophies of Athens and Jerusalem, saying, “Socrates criticised and argued, he never shed a tear. Why does Socrates never cry? Because he never loved deep enough, human beings – he loved wisdom in the abstract.

“Jesus weeps, Jeremiah cries; why? Because when you love human beings – the way that you [turning to Murray] have talked about with such eloquence – you go beyond self-mastery. Your mama’s funeral? That’s not the moment to be exemplary of self-mastery! Tears will flow because of the love, the depth, the sacrifice, the service that have been rendered to you.

“Now, religious folk call that piety … the secular philosopher called it natural piety – the acknowledgment of the sources of good in your existence and the degree to which you are dependent on those who come before. And that’s every human being, no matter what.

“And therefore, this whole notion of different communities, different people, the hell they’ve been through but also the heaven that they’ve created under hellish conditions … it’s a human connection. And if we are about anything in these dialogues, it’s about a human connection, even given deep disagreements.

“Because in the end, even as we go down swinging, it don’t mean a thing, if it ain’t got that swing.”

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?