Lockdown, the end of the diary … and more serious issues about the past, present and future

Lewis Jones says that COVID tempts us to turn inward and look after ourselves in the face of uncertainty. But God tells us to look to him.

The ongoing COVID crisis has made the present so different from the past – even the recent past – in such significant ways, that it feels like the past has become irrelevant; a quaint memory of no predictive or pedagogical value. COVID has also made us feel like the future no longer even exists. Our government now tells us how long into the future we are allowed to dream and plan: sometimes a week, sometimes two.

Our little lockdowns here in New South Wales are the only times of reasonable stability and predictability. They’re the only times we can be pretty sure that nothing will change precipitously. It’s only in lockdown that we can plan, i.e. plan for the two weeks of lockdown.

To emerge from lockdown is to emerge into true uncertainty. We can go back to church and not wear a mask everywhere, but the future loses any guarantee. In lockdown, decisions are reduced. Out of lockdown, we’re back into the anxious half-freedom of complex public health orders and the massive multiplication of daily decisions. The only thing we feel confident about outside of lockdown is that we could end up in lockdown again at any moment. We are not free to plan or dream or hope. We are slaves of the present.

We who are Christians know we are not in control of the world. But in the past, the world has, at least, been predictable enough to allow us to establish routines which produce a sense of stability and comfort. The regularity of our lives allows us to interact with family and friends and our communities from a position of relative confidence and love and grace and forgiveness.

Being cut off from the past and future makes our present constantly anxious, because we no longer know how to anchor our actions.

When we don’t know what tomorrow will bring, we tend to first look after ourselves to re-establish that confidence before we look outward in service of others. The problem is, these days, that confidence just won’t come. There is nothing I can do today to set myself up for tomorrow. Tomorrow might exist in my diary, but it doesn’t exist in my imagination. That is, I struggle to persuade myself that tomorrow will happen the way I planned it.

If we do make plans, we do so only cynically, with no expectation of following through.

Being cut off from the past and future makes our present constantly anxious, because we no longer know how to anchor our actions. We have to plan because the act of planning is the only thing that gives us a sense of purpose and hope. Our diaries relentlessly remind us that we used to believe in this thing called the future and our memory of having a future is still strong enough to fool us into thinking it’s real. On the other hand, our planning is cynical and wearisome because COVID has taught us that our memories of this fabled future are fickle, and that the future, as it appears in our diaries, won’t really come in any way we can predict.

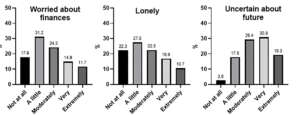

Not everyone who reads this will be as despondent about the future as what I’ve outlined above, but there’s now good reason to think that’s how a lot of Australians really are feeling. In recent research, almost 80 per cent of adults (see also table below) and 64 per cent of adolescents (see also table in Part One) reported moderate to extreme levels of uncertainty about the future.

What’s interesting about this survey is: uncertainty about the future was a much stronger predictor of anxiety, stress, and depression than responses specific to COVID-related experiences. This suggests that worry about the future has become a broad proxy for describing our COVID times.

How can we respond to the way COVID seems to have erased the future? And how can we respond in ways that encourage us to continue to love God and love our neighbour?

We Christians can be tempted, like everyone else, to attempt to secure our future through human ingenuity or government control. In the midst of our uncertainty, we are in danger of turning inward to look after ourselves as we desperately seek some sort of control over our environment. But that sort of control is built on sand rather than solid rock. “Stop trusting in mere humans, who have but a breath in their nostrils.” (Isaiah 2:22)

The bedrock of our confidence in the present is that the future exists simply because God is not finished with history. History is not the naturalistic winding down of the cosmic clock due to the second law of thermodynamics. History is the purposeful interaction of God with his creation to bring about his ends that he specified before he ever created anything. The structure of history is the movement from promise to fulfillment. That is the arrow of time; not the monotonic increase of entropy in our universe. The promises of God create the future and secure the outcome.

God’s people know who they are and how they are to live even in the midst of genuine uncertainty.

For all the variety and timing of God’s many promises throughout the Scripture, there is one focus of them all and one fulfillment of them all: the Lord Jesus Christ (2 Corinthians 1:20). And so it is to Jesus we look for our guarantee of God’s future even as we struggle with an unpredictable present. We have the words of the prophets made more sure in Christ (2 Peter 1).

Abraham died having not received what was promised (Hebrews 11), because it was only with us and in Christ that he was ever to receive it. But he lived by faith everyday within the trajectory of promise to fulfillment, trusting the future because he knew the faithful God who made the promise.

Jesus’ resurrection demonstrates that the future exists. In Luke 24:46-47, Jesus told his disciples:

“This is what is written: The Christ will suffer and rise from the dead on the third day, and repentance and forgiveness of sins will be preached in his name to all nations, beginning at Jerusalem.”

This means the Christ event is not punctiliar, but extended, in time. Jesus has died and risen and ascended to the Father, but that is not the end for he has promised that he will return. History marches on until that day. The promise of Jesus’ death and resurrection is that he will return to judge the world and to bring his people, those who have trusted in him, into the new creation. The future exists; not because of human ingenuity, nor our control of our environment, but because of Jesus.

We now live by faith on the trajectory between that promise and fulfillment. And far from being uncertain about how to act in these genuinely unpredictable times, the Scripture is abundantly clear about how to live on the current trajectory. Jesus tells us that the task now is to preach repentance and forgiveness of sins in the name of Jesus to all nations (Luke 24:46-47); also, to make disciples of all nations (Matthew 28:18-20). And, in response to the grace of God in Christ, we say no to ungodliness and worldly passions and live self-controlled, upright, and godly lives while we await his return (Titus 2:11-14).

Ironically, after all that, we confess the timing of our future is indeed uncertain. “[T]he Son of Man will come at an hour when you do not expect him” (Matthew 24:44). But that uncertainty affects neither how I live today nor the final outcome. The outcome is determined by God, has been revealed in the Scripture, and I live today in light of his promise. I cultivate the fruit of the Spirit today because that will make me more suited for my ultimate home regardless of whether Jesus returns tomorrow or in ten years or 1,000 years. I preach Christ crucified today because Jesus says that is where we are on the trajectory. More than that, I also plan today to preach Christ crucified tomorrow because I must honour the fact that I do not know when Jesus will return and, hence, prepare myself for a lifetime of preaching Christ.

God’s people know who they are and how they are to live even in the midst of genuine uncertainty. Our confidence in the present and our hope for the future should also make us useful to our neighbours. Being confident in our own future, we can look outward and serve others, not hoarding for the present, but generously giving ourselves in the service of God. Our confidence can also be a beacon for God’s hope that will challenge and draw people to Christ.

The future is secure because our faithful God is not finished with history; he has promises yet to fulfill. Jesus Christ has died, risen, and ascended and we now live by faith on the trajectory toward his return.

Lewis Jones has a PhD in Astrophysics and is a graduate of Moore Theological College. He works for AFES, leading The Simeon Network, a network of Christians working in academia. He is interested in apologetics, particularly the interaction of Science and Christianity, and dabbles in Liberal theory. He is a member of Randwick Presbyterian Church, where he is an elder. Lewis is a member of the Gospel, Society and Culture Committee of the Presbyterian Church of NSW.

*First published by the Gospel, Society and Culture committee. Used with permission.

Part One is here.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?