The Yorta Yorta elder and the Holocaust survivor: the politics of hope

The lessons of their alliance for today’s religious freedom fighters

Trudge the hill to federal parliament on a sitting day, and it’s hard not to trip over an activist. Financial industry lawyers push in with their ristrettos. Climate protesters set fire to their prams. It can get busy.

Jostling between them, you find church leaders. All nerves and polite nods, they’re off to press an MP for religious freedom. They unplug their ears from a trending Ben Shapiro podcast, rehearse their talking points, and wait in the eucalypt-green marble foyer.

But parliamentarians aren’t racing out to see them. If I had the chance to lift their spirits as they wait on that hardwood bench, I’d recommend they look to those influencers from the time before influencers. In particular, an Aboriginal Christian elder called William Cooper.

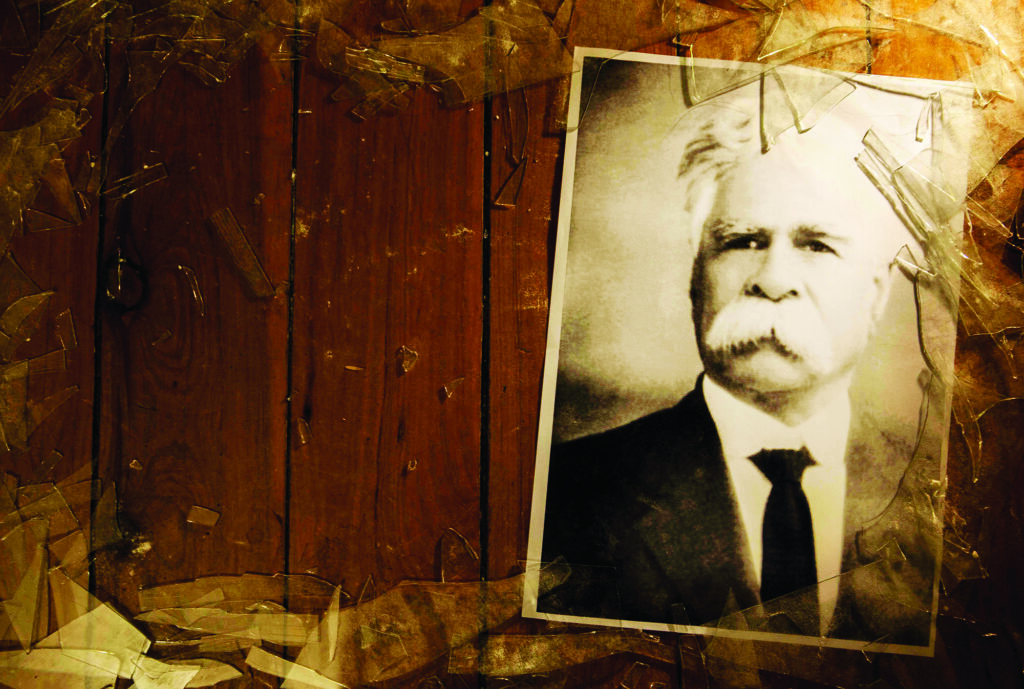

In 1938, William Cooper was 78, still barrel-chested, with a magnificent white walrus moustache. While others were retiring, he became the first Aboriginal leader to broker a meeting with a sitting Prime Minister.

Cooper’s home in Southampton Road in Melbourne’s Footscray was a long way from the Barmah Forest where he was born. Cooper’s grandson, Boydie, who’s still with us, says it was a serious place, quite cold during winter because Cooper would rather spend his pennies on the ink and stamps needed for his letter-writing campaigns. He’d been taught to read and write by a missionary at a place called Maloga. His handwriting was beautiful — one of many arts that lobbyists have lost today.

There were times of joy in Cooper’s home too. Uncle Boydie says every planning meeting began with prayers and songs such as “There is a happy land, far, far away”. Which makes me wonder, how many lobbyists sing before they make their PowerPoint presentations?

For Cooper, psalms, hymns and spiritual songs were part of doing politics well. All the early Indigenous justice leaders in Victoria were Christians, with connections going back to church communities at the Maloga, Cummeragunja, Ebenezer or Coranderrk missions.

“Have faith in God … Incline your heart anew unto the Lord … And the Lord will give thee victory over thine enemies.”

It’s not so much the songs that gave these political operators their edge. It was the hope. Which is something you hardly ever hear in Christian podcasts about politics. Cooper’s people had heads full of songs like, “There is a happy land” and the Yorta Yorta Exodus song “Bura Fera”, which gave everyone the sense that, no matter the setback, justice for God’s people is only a matter of time. You can sense the optimism in a note Cooper wrote to a friend in Adelaide, rich with hope that comes straight from the Psalms:

“Have faith in God … Incline your heart anew unto the Lord … And the Lord will give thee victory over thine enemies.”

Cooper’s campaigns were spiritually driven and highly effective. His indigenous umbrella group, the Australian Aborigines League, created national headlines. When he began a petition to the King, with signatures from Aboriginal people from all over the country, it made the idea of federal oversight for Aboriginal welfare a matter for cabinet. The 1967 Referendum made that change permanent, but the idea dates back to Cooper’s campaign of the 1930s.

William Cooper Simon McGrath

I believe the best way to judge the effectiveness of a campaign is how long you sense its effects. It was four years ago, listening to a Holocaust survivor, I realised that William Cooper was singular in his effectiveness as a Christian political operator.

“I’m here tonight to add my thanks to you the Aboriginal people for having created a family like William’s.” – Eddie Jaku

I was sitting in the Australian Hall on Elizabeth Street in Sydney (where Cooper and his colleagues had convened a “Day of Mourning” in the 30s). With me was Uncle Boydie, William Cooper’s grandson, along with the Redfern community leader Uncle Shane Phillips and dozens of community members. But the man speaking about William Cooper was Jewish; a microphone in his right hand, and the number 72338 tattooed on his left forearm.

The man was Eddie Jaku. A 97-year-old survivor of Auschwitz, he began his speech by addressing the Indigenous community, “I’m here tonight to add my thanks to you the Aboriginal people for having created a family like William’s.”

What had William Cooper achieved for Eddie Jaku? To understand that, you need to get a picture of geopolitics in 1938. In July of that year, Australia was one of several Western nations invited to the Evian Conference on Lake Geneva. The agenda was which countries were going to welcome the millions of Jews being forced out of Europe. The answer from Australia, given by the Minister for Trade and Customs at the time, is one of the most shameful moments in our national story:

What had William Cooper achieved for Eddie Jaku? To understand that, you need to get a picture of geopolitics in 1938. In July of that year, Australia was one of several Western nations invited to the Evian Conference on Lake Geneva. The agenda was which countries were going to welcome the millions of Jews being forced out of Europe. The answer from Australia, given by the Minister for Trade and Customs at the time, is one of the most shameful moments in our national story:

“…as we have no real racial problem, we are not desirous of importing one by encouraging any scheme of large-scale foreign migration…”

By November, Australia was still refusing to welcome even a small number of the Jews escaping Nazi Germany. Even as the brownshirts burnt 1000 synagogues and herded 30,000 Jewish men in concentration camps on the night that became known as Kristallnacht. One of the young men rounded up that night, at 5am, was 20-year-old Eddie Jaku.

Real freedom is about insisting there is room for everyone to live out their deepest convictions.

As Eddie was shunted to Buchenwald, William Cooper and his Australian Aborigines League began planning a response. On 5 December, these Indigenous people, marched from Southampton Street in Footscray to confront Dr Dreschler, Consul General of the Third Reich, demanding an end to the persecution of the Jews. Yad Vashem, the Holocaust research centre in Jerusalem, said this protest march was the only protest of its kind.

That day, William Cooper showed all people of faith what real religious freedom is about. It’s not about protecting your patch. Real freedom is about insisting there is room for everyone to live out their deepest convictions. Here was a black Australian Christian standing up for the liberty of European Jews, and sending the signal they are welcome here. He played his part in pressing for the passenger ships of Jews to start arriving. And the impression that left on our Australian political life has never been forgotten.

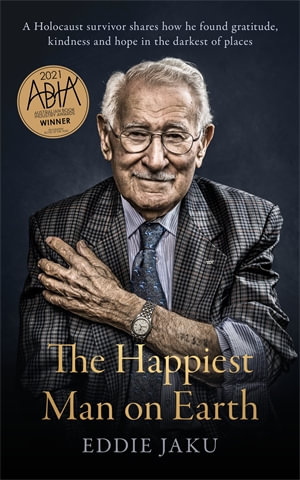

It left an enduring impression on Eddie Jaku, who, having evaded death in Auschwitz, called himself, “The happiest man on earth.” When he spoke to William Cooper’s grandson, he said: “We never believed that men so far from Germany would do that for us … Thank you … I never thought I would meet the man who is a relative of a man like your grandfather. I applaud you.”

Mr Jaku died at Montefiore this week aged 101. A Jew who felt like he had beaten all his enemies because “my victory is that I don’t hate.” It’s a victory that he shared with a Christian Indigenous man, who showed his countrymen how to live out the politics of hope.

Matt Busby Andrews is a communications consultant based in Canberra.

Watch Eddie Jaku speaking at “Dreaming of Freedom: Honouring William Cooper” on September 3, 2017, here.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?