What could have helped Marty Sampson's faith

Michael Frost wonders if more disciple makers are needed

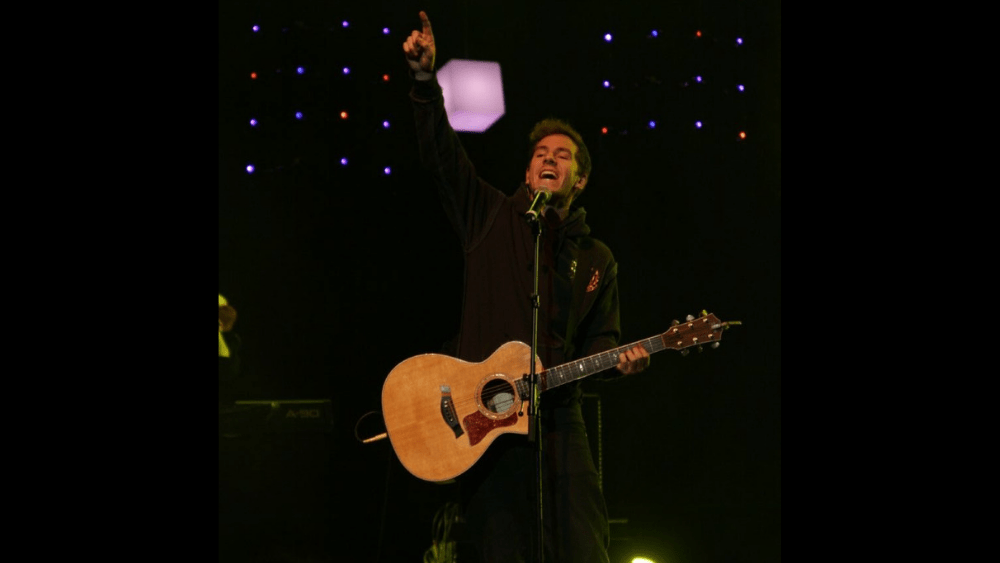

Yet another high profile Christian leader has taken to Instagram to announce that he is giving up on Christianity. Marty Sampson, a much-loved songwriter and performer with the bands, Hillsong Worship, Hillsong United, Delirious?, and Young & Free, recently posted: “I’m genuinely losing my faith, and it doesn’t bother me. Like, what bothers me now is nothing. I am so happy now, so at peace with the world. It’s crazy.”

I don’t mean there are easy answers … but there are plenty of resources out there for developing a robust faith

The news left a legion of followers reeling. Many people are grieving. One of my friends called it “an unexpected gut punch.”

This follows Joshua Harris’s similar Instagram announcement that he longer considers himself a Christian. Harris was previously one of the leaders of the American evangelical purity culture movement.

But it feels as though Sampson’s decision has affected people here more than Harris’ – and much more than other recent high-profile losses of faith by people such as Michael Gungor, Bart Campolo or Frank Schaeffer.

For this, reason it’s worth spending some time looking at Sampson’s ‘Dear John’ letter to his faith, to try to make sense of what might have precipitated it being on “incredibly shaky ground“. (Sampson told Christian Post this week that “Christianity just seems to me like another religion at this point.”)

In that now-deleted Instagram post, Sampson wrote: “How many preachers fall? Many. No one talks about it. How many miracles happen. Not many. No one talks about it. Why is the Bible full of contradictions? No one talks about it. How can God be love yet send four billion people to a place, all ‘coz they don’t believe? No one talks about it.”

Did you get that? He’s shaken by the moral failure of leaders, a lack of miracles, the challenges of biblical hermeneutics, and questions about theodicy and eternal punishment. And in particular, he’s distressed that no one talks about it.

When I first read that, I thought, “But I talk about that stuff. A lot!”

The more I reflected on it, the more I realised that whenever I do talk or write about those things, I get howled down by other Christians telling me I shouldn’t be so discouraging. I’m often told I should build up the church, not tear it down. I’m regularly reprimanded for criticising God’s anointed leaders. I’m routinely gaslighted as grouchy or a stirrer.

And here’s the problem, as I see it. If we foster a church culture where hard questions can’t be asked and answers can’t be attempted, we end up with the kind of brittle faith that Sampson is now shedding.

I say brittle because none of the issues he mentions are that difficult to address. I don’t mean there are easy answers to them. But there are plenty of resources out there for developing a robust faith that can integrate the breadth of perspectives reflected in Scripture; that can make sense of a lack of miracles; that can embrace the tension between God’s love and God’s judgement; and that can be unshaken by derelict leadership.

I have friends at Hillsong who know and love Marty. They tell me there are plenty of people he could have spoken to about his doubts and questions. So, why didn’t he? Why does he repeat over and over, “No one talks about it”?

Was it that he became a public Christian too young without the grounding and the discipline to continue to flourish in his faith while still asking the awkward questions? Did he feel that as a Christian celebrity he wasn’t able to express his doubts incrementally, as they arose? And, now, all those questions about hermeneutics and science and disappointing leadership have heaped up and broken open the walls of his faith.

Marty Sampson’s announcement made me think of an even more famous young Christian from a previous era.

It wasn’t tyranny, it was elderhood.

In 1941, the man who would become known as Thomas Merton, entered the Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemani in New Haven, Kentucky, to begin monastic life. A brilliant, restless man, constantly curious, always appearing to juggle multiple ideas at the same time, Merton was quite a handful for his superiors.

None of the other 200 or so monks at Gethsemani taxed the sympathies and patience of their abbot like Merton did.

Many of his interests – Zen asceticism, peace activism, the Civil Rights movement, Christian ecumenical dialogue, French Existentialism, the history of Communism, and a thousand other things — lay far outside the concerns and interests of his superiors, who struggled to focus their new recruit.

But then, in 1948, Dom James Fox, a former military officer and graduate of Harvard Business School, was appointed the abbot at Gethsemani. Fox would go down in history as the monk who kept a lid on the dazzling intellect of Thomas Merton. Indeed, one of Merton’s biographers, Monica Furlong, claimed Fox exercised a kind of tyranny over him.

But Dom James knew exactly what Thomas Merton needed.

James Fox imposed restrictions on Merton, it’s true, but his intent was to help the difficult and complex young monk to flourish, not to snuff out his flame. It wasn’t tyranny, it was elderhood.

At that time, Merton was a world-famous author of unbounded curiosity and intelligence. He wanted to pursue a thousand interests, to read voraciously on an endless range of complex subjects, to correspond with hundreds of adoring fans. But Dom James restricted his writing time, focused his contemplative life, insisted he continue his theological study.

He anchored him.

He deepened him.

He allowed him to exercise his role as the preeminent public Christian of his time. But he released Merton into the world in short, manageable bursts. Fox stewarded Merton’s genius by tempering it with discipline, solitude, study and service.

Fox died in 1968, and his successor was so intimidated by Merton’s fame he allowed him to do whatever he wanted. If James Fox had been like that twenty years earlier, I suspect Merton would have flamed out, or left the monastery, or embraced Buddhism, or something similar.

Finding genuine truth happens through the life-tested skill of gathering what is needed to sustain faith without killing faith in the gathering.

I share this story because I suspect churches need more James Foxes, men and women who know how to help the Marty Sampsons and Thomas Mertons to flourish through discipline; men and women who aren’t shocked by the so-called wrong questions; men and women who produce growth in us by limiting us, pruning us, feeding us.

Would a James Fox have let Joshua Harris write I Kissed Dating Goodbye at age 21?

Would a James Fox have let Marty Sampson get to age 40 without a robust theology of the miraculous or the afterlife?

In his Instagram post, Sampson grouses, “I am not in any more. I want genuine truth. Not the ‘I just believe it’ kind of truth”.

And that’s the gist of it. Genuine truth.

In our information-drunk, effectiveness-addicted culture, finding genuine truth happens through the life-tested skill of gathering what is needed to sustain faith without killing faith in the gathering. We need elders, mothers, and abbots to help us.

We need flinty truth-tellers, men and women of deep faith, who haven’t stopped asking their cranky questions, and who give permission to us all to ask and ask and ask until we too have found genuine truth.