A basket of ten staple foods costs about one hour’s worth of work for the average Australian. But if you live in Syria, the cost is equivalent to three day’s worth of work.

In South Sudan, that basket takes the average worker eight days of work to pay for it.

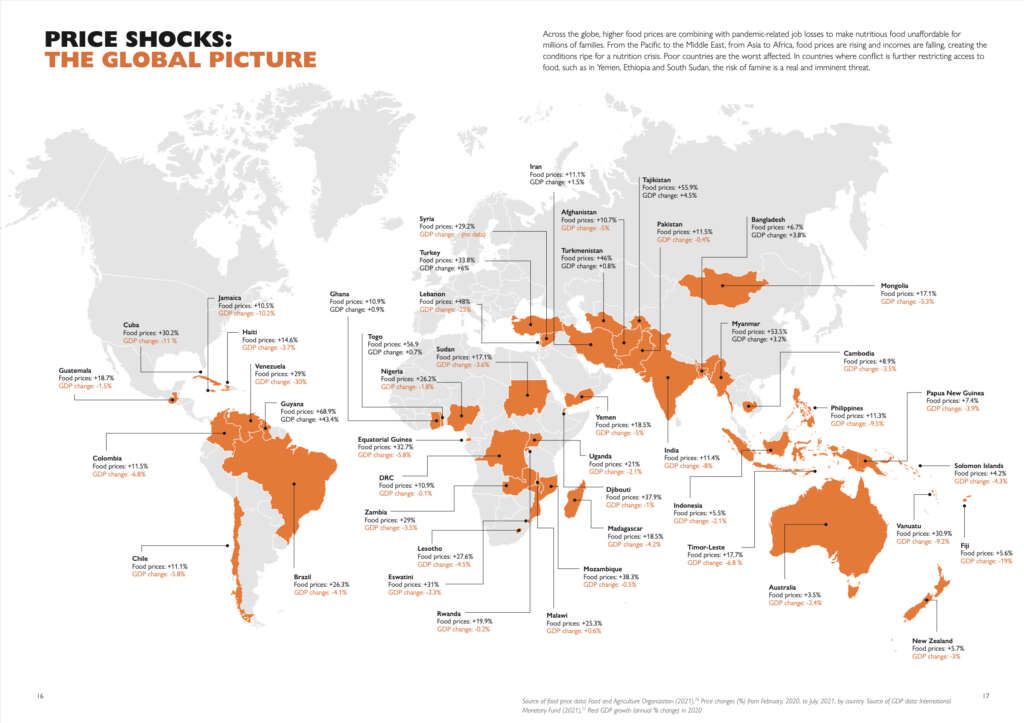

That’s because the cost of food has soared by more than 50 per cent since the pandemic began in places like Syria, east Africa or Myanmar, according to Price Shocks, a report released by World Vision today.

While average food prices rose just 3.5 per cent in Australia over the 18 months of the pandemic, prices for the same items shot up in poor countries where food accounts for a larger share of household budgets.

Price Shocks found between February 2020 and July 2021, while Australian food prices rose by just 3.5 per cent, prices increased in Myanmar by 54 per cent, Lebanon 48 per cent, Mozambique 38.3 per cent, Vanuatu 30.9 per cent, Syria 29.2 per cent and Timor-Leste 17.7 per cent – affecting mainly people who could least afford it.

The research also found around 161 million more people went hungry in 2020 compared with 2019 – a 25 per cent increase. Most worryingly, more than 41 million people are suffering emergency levels of food insecurity and/or famine-like conditions across Africa and the Middle East.

“Job losses and lower incomes from the pandemic are forcing millions of families to skip meals, go for cheaper, less nutritious food, or go without food altogether” – Daniel Wordsworth, World Vision

World Vision says that higher prices and lower incomes since COVID-19 have put healthy food beyond the reach of around three billion people.

“Job losses and lower incomes from the pandemic are forcing millions of families to skip meals, go for cheaper, less nutritious food, or go without food altogether,” said World Vision Australia CEO Daniel Wordsworth.

Soaring food prices combined with lockdown-induced job losses and disrupted nutrition services now mean that more people are dying each day from hunger than from COVID-19 itself.

The report cites a recent study which estimated by the end of 2022, the nutrition crisis caused by COVID-19 could result in 283,000 more deaths of children aged under five, 13.6 million more children suffering from wasting or acute malnutrition and 2.6 million more children suffering from stunting. This would equate to 250 children dying each day from pandemic-related malnutrition.

“As always, children suffer the most – they are the most vulnerable to hunger because they have a greater need for nutrients, they become undernourished faster than adults and are at a much higher risk of dying from starvation,” Wordsworth said.

“And this is not only about hunger or malnutrition – it’s also about how families cope, how they resort to desperate measures such as child marriage and child labour to put food on the table.

“If we don’t arrest the hunger situation soon, we’re talking about the potential scarring of a whole generation of children. It’s a recipe for disaster.”

Wordsworth said he was confident Australians wouldn’t just stand by and watch the crisis spiral out of control, but would step up to help organisations like World Vision provide emergency food and cash assistance to those in need.

In 2020, World Vision reached 12 million of the world’s most vulnerable people in 29 countries with food and nutrition.

Now, the organisation is urging the Australian Government to commit $AU150 million famine-prevention package to avert a worsening of the crisis.

“Together, we can prevent the worst of this hunger crisis. But we can’t do this alone. That’s why we’re asking the Australian Government to join with us and fund this famine-prevention package, because there’s no place for famine in the 21st century,” Wordsworth said.

Across the globe, higher food prices are combining with pandemic-related job losses to make nutritious food unaffordable for millions of families. From the Pacific to the Middle East, from Asia to Africa, food prices are rising and incomes are falling, creating the conditions ripe for a nutrition crisis. Poor countries are the worst affected. In countries where conflict is further restricting access to food, such as in Yemen, Ethiopia and South Sudan, the risk of famine is a real and imminent threat. – From Price Shocks, World Vision.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?