When possible cases of repressing “religious speech” are reported, sometimes the speaker has done more than simply say what the Bible says – unruly language and personal disputes can be involved. This can complicate defending the case.

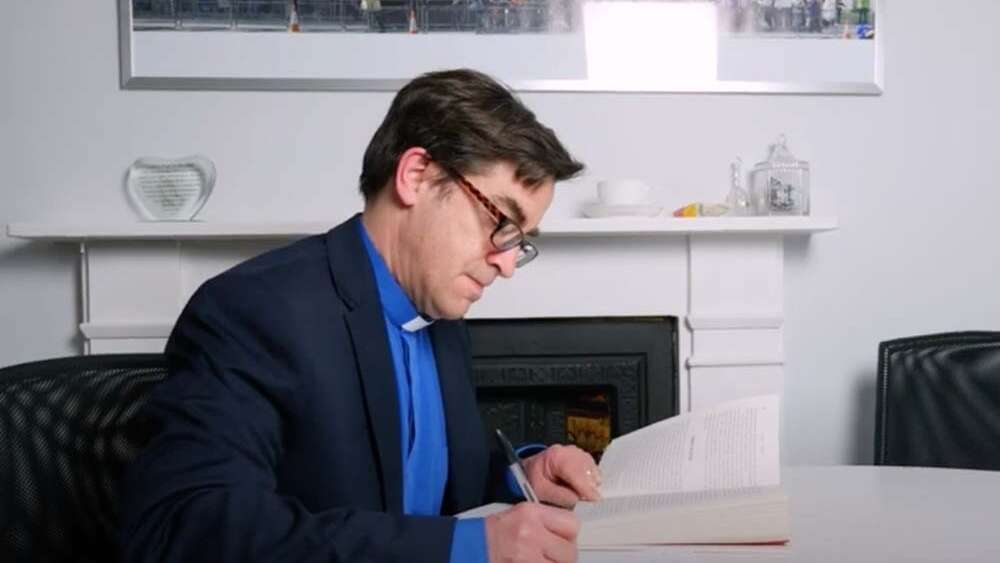

But a clear-cut case has just surfaced in Britain, where a mildly expressed sermon has caused a school chaplain – in an Anglican school – to be flagged by the school to an official anti-terrorism watchdog called “Prevent”. After the police found that the sermon posed “no counter-terrorism risk, or risk of radicalisation”, the chaplain, Bernard Randall, was told his sermons would need to read by school authorities before being preached. He was later sacked.

Randall is an ordained Church of England minister and a former chaplain of Christ’s College, Cambridge.

“I never thought preaching a sermon would see me dismissed, reported to Prevent, and treated in such a way,” he told Christian Concern, a campaigning group. The Sermon was in response to a student asking him, “‘How come we are told we have to accept all this LGBT stuff in a Christian school?’”

He is now launching a legal challenge against his sacking.

The sermon is worthy reading to gauge what can get you sacked in the UK.

The sermon:

I have a theory about Brexit. It seems to me that people who voted to leave the European Union voted for largely political reasons – to do with democratic self-determination; and people who voted to remain did so for largely economic reasons – to do with prosperity and jobs.

Of course I’m simplifying here, and both sides claim to consider both, but it seems to me that which set of ideas, which ideology, takes priority determines which way many people voted.

By all means discuss, have a reasoned debate about beliefs, but while it’s OK to try and persuade each other, no one should be told they must accept an ideology.

And while we can easily discuss facts, and try to find the truth behind factual claims, ideals aren’t true or false in the same way.

And so the problem with the often very heated and unpleasant debate ever since the referendum is that people haven’t managed to cope with there being two competing sets of ideals – two ideologies.

Now when ideologies compete, we should not descend into abuse, we should respect the beliefs of others, even where we disagree. Above all, we need to treat each other with respect, not personal attacks – that’s what loving your neighbour as yourself means.

By all means discuss, have a reasoned debate about beliefs, but while it’s OK to try and persuade each other, no one should be told they must accept an ideology. Love the person, even where you profoundly dislike the ideas. Don’t denigrate a person simply for having opinions and beliefs which you don’t share.

There has been another set of competing ideals in the news recently. You may have heard of the protests outside a Birmingham primary school over the teachings of an LGBT-friendly ‘No Outsiders’ programme.

In a mostly Muslim community, this has been sensitive, because many parents feel that their children are being pushed to accept ideas which run counter to Islamic moral values.

And in our own school community, I have been asked about a similar thing – and the question was put to me in a very particular way – ‘How come we are told we have to accept all this LGBT stuff in a Christian school?’ I thought that was a very intelligent and thoughtful way of asking about the conflict of values, rather than asking which is right, and which is wrong.

So my answer is this: There are some aspects of the Educate and Celebrate programme which are simply factual – there are same-sex attracted people in our society, there are people who experience gender dysphoria, and so on.

There are some areas where the two sets of values overlap – no one should be discriminated against simply for who he or she is: That’s a Christian value, based in loving our neighbours as ourselves.

All these things should be accepted straightforwardly by all of us, and it’s right that equalities law reflects that.

But there are areas where the two sets of ideas are in conflict, and in these areas you do not have to accept the ideas and ideologies of LGBT activists. Indeed, since Trent exists ‘to educate boys and girls according to the Protestant and Evangelical principles of the Church of England’, anyone who tells you that you must accept contrary principles is jeopardizing the school’s charitable status, and therefore it’s very existence.

You are not obliged to accept someone else’s ideology. You are perfectly at liberty to hear ideas out, and then think, ‘No, not for me’.

You should no more be told you have to accept LGBT ideology than you should be told you must be in favour of Brexit, or must be Muslim – to both of which I’m sure most of you would quite rightly object.

I am aware that there will be a good few in our community who will have been struggling, if they feel they are being told that they must accept ideas which run counter to their faith – or indeed non-faith – based reasoning about the world.

So I want to say to everyone, but especially to those who have been troubled, that you are not obliged to accept someone else’s ideology. You are perfectly at liberty to hear ideas out, and then think, ‘No, not for me’.

There are several areas where many or most Christians (and, for that matter, people of other faiths, too), will be in disagreement with LGBT activists, and where you must make up your own mind. So it is perfectly legitimate to think that marriage should only properly be understood as being a lifelong exclusive union of a man and a woman; indeed, that definition is written into English law.

You may perfectly properly believe that, as an ideal, sexual activity belongs only within such marriage, and that therefore any other kind is morally problematic. That is the position of all the major faith groups – though note that it doesn’t apply only to same-sex couples.

And it is a belief based not only on scripture but on a highly positive view of marriage as the building block of a society where people of all kinds flourish, and on recognising that there are many positive things in life more important than sex, if only we’d let them be.

This viewpoint is recognised by many people as extremely liberating. And it’s an ethical position which could also be arrived at independently of any religious text, I think.

In other areas you are entitled to think, if it makes more sense to you, that human beings are indeed male and female, that your sex can’t be changed, that although the two sexes have most things in common, there are some real, biologically based differences between them overall. And if you think that, you would be in accord not only with the tradition of most Christians, and other faiths, but much of the biological and psychological sciences too.

You are entitled, if you wish, to look at some of the claims made about gender identity and think that it is incoherent to say that, for example, gender is quite independent of any biological factor, but that a person’s physiology should be changed to match his or her claimed gender; or incoherent to say that gender identity is both a matter of individual determination and social conditioning at the same time, or incoherent to make claims about being non-binary or gender-fluid by both affirming and denying the gender stereotypes which exist in wider society.

And if these claims, which do seem to be made, are incoherent, then they cannot be more than partially true. Yet truth is important as we try to make decisions about the consequences of these ideas.

And you might reasonably notice that some LGBT activists will happily lie about gender identity being a legally protected characteristic (which it isn’t), and from that observation wonder whether there are other areas where their relationship to truth is looser than might be ideal.

But, by way of contrast, no one has the right to tell you that you must lie about these matters, to say things you sincerely believe to be false – that is the tactic of totalitarianism and dictatorship.

We should all respect that people on each side of the debate have deep and strongly held convictions.

On a more positive note, Christians will want to have a discussion about human identity which focuses on the things we all have in common, rather than increasingly long lists of things which might divide.

You might be concerned that if you take the religious view on these matters you will be attacked and accused of homophobia and the like. But remember that religious belief is just as protected in law as sexual orientation, and no one has the right to discriminate against you or be abusive towards you.

Remember too that ‘phobia’ words have a strict sense of extreme or irrational fear or dislike, like arachnophobia, fear of spiders, or triskaidekaphobia, fear of the number thirteen – well, there’s nothing extreme about sharing your view with the Church of England, established by law, and of the majority of the world’s population who belong to these faiths.

Nor is it irrational to hold these views, since they can be based both on secular reasoning and on scriptures – and if, on other grounds, you are sure that the scriptures reflect the mind of God, then they provide the very best reasons possible for anything.

But ‘homophobia’ and ‘transphobia’ have come to be used in a looser sense to mean often simply, ‘You disagree with me and I’m going to refuse to listen to you, and shame you to shut you down’. In other words, they have sometimes come to be terms of abuse, used in a dictionary-definition, bigoted and bullying way. You can safely ignore these uses, although that takes real moral courage, I know.

And you may think that LGBT rights are different somehow, because no one chooses to belong to the varied groups represented by these ideas. To which I would remind you that equalities law does not recognise that distinction – all equalities are in fact equal.

So, all in all, if you are at ease with ‘all this LGBT stuff’, you’re entitled to keep to those ideas; if you are not comfortable with it, for the various especially religious reasons, you should not feel required to change.

Whichever side of this conflict of ideas you come down on, or even if you are unsure of some of it, the most important thing is to remember that loving your neighbour as yourself does not mean agreeing with everything he or she says; it means that when we have these discussions there is no excuse for personal attacks or abusive language.

We should all respect that people on each side of the debate have deep and strongly held convictions. And because, unlike Brexit, this is not a debate which is subject to a vote, it is an ongoing process, so there should be a shared effort to find out what real truth looks like, and to respect that that effort is made honestly and sincerely by all people, even if not everybody comes up with the same answers for now.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?