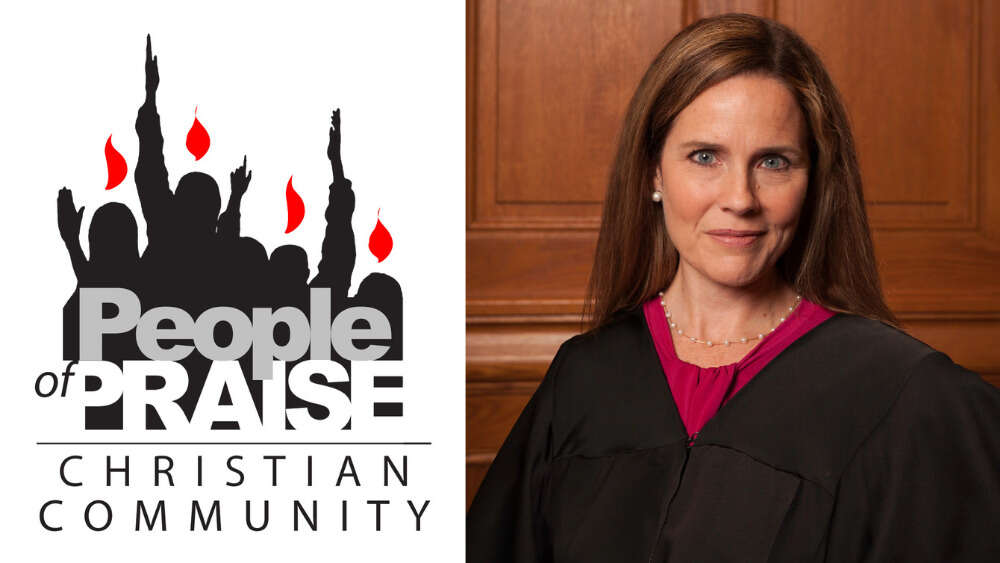

“Secretive”, “cult”, “small religious group”: these are the kinds of words found in media articles describing the “People of Praise” – the Charismatic Christian group of which United States Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett is a member.

Founded in 1971 in South Bend, Indiana, the People of Praise is a community of about 1700 members with a presence in 22 cities across the US, Canada and the Caribbean.

With contemporary media’s religious literacy at low levels and the hyper-partisan context of the US election, this Christian community is coming under intense scrutiny.

“Trump’s pick is a member of a ‘covenant community’ that faces claims of a ‘highly authoritarian’ structure,” declares Australian news outlet The Guardian – scary language that screams “extremism!” to the average reader, no doubt.

But for most practising Christians, the term “covenant” isn’t at all unfamiliar or concerning language. And the accusation of an organisation “facing claims of a ‘highly authoritarian’ structure” could be levelled at almost any organisation on earth – be it a political party, large corporation or a sporting club.

So who are the People of Praise, when the fog of partisan rhetoric and the media’s religious illiteracy are waved away? Here are a few key points to know about the Christian group in the headlines.

The People of Praise are big on being a community – and you can formalise your commitment to being part of the community

Most Christians have a sense that the best churches are the ones where the people involved don’t just attend, they’re a community. So, we make some level of a commitment to each other when we become part of a church community.

Some become members of a church, agreeing to attend meetings, voting on the church’s ministries, budget and staff appointments. Some take on extra leadership roles – like eldership – agreeing to a code of conduct themselves and the fulfillment of various responsibilities. Some make an informal commitment to being good members of the community – being there to share life’s moments and do what the Bible instructs – “weep when others weep” and “laugh when others laugh”.

Many Christians also have another Christian community we are part of – as well as our church – where we unite across denominations. In Australia, for example, there’s the network of chaplains in Chaplaincy Australia, the Anabaptist fellowship or SPARC – the community of Christian artists – and those Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders who are part of the Grasstree gathering.

This second type of community is more that of the People of Praise. They are a charismatic community of Christians from different denominations.

“Jesus desires unity for all people. We live out this unity the best we can, in spite of the divisions within Christianity,”explains the group’s website. “People of Praise is a Christian community whose members come from more than 15 different Christian denominations and churches. We aim to share our daily lives together in community, while also remaining faithful and active members of our own particular churches and denominations … Despite our differences, we are bound together by our Christian baptism. Despite our differences, we worship together. While remaining faithful members of our own churches, we have found a way to live our daily lives together.”

The difference is that the People of Praise take their commitment to being in community more seriously than most.

“Our community life is characterised by deep and lasting friendships. We share our lives together, often in small groups and in larger prayer meetings. We read Scripture together. We share meals together. We attend each other’s baptisms and weddings and funerals. We support each other financially and materially and spiritually. We strive to live our daily lives in our families, workplaces and cities in harmony with God and with all people.”

Becoming a member of the People of Praise is voluntary and is called a “covenant commitment”

For most Christians, the word “covenant” expresses a beautiful, biblical concept that describes people making a voluntary agreement to be in a committed relationship to one another. There’s a marriage covenant, of course. But Christians also believe in a covenant-keeping God – and are grateful for this aspect of God’s nature. This is a God keeps his covenant of love to a thousand generations – even when his people fall short of keeping theirs.

The word is also sometimes used to describe a relationship within a Christian community, and that’s how People of Praise use it.

“Community life in the People of Praise is grounded in a lifelong promise of love and service to fellow community members. This covenant commitment, which establishes our relationships as members of the People of Praise community, is made freely and only after a period of discernment lasting several years. Our covenant is neither an oath nor a vow, but it is an important personal commitment. We say that People of Praise members should always follow their consciences, as formed by the light of reason, and by the experience and the teachings of their churches,” their website says.

So, can a covenanted member leave the People of Praise?

“Yes. We have always understood that God can call a person to another way of life, in which case he or she would be released from the covenant.”

They’re charismatic … and, yes, that means they believe in speaking in tongues

“Like hundreds of millions of other Christians in the Pentecostal movement, People of Praise members have experienced the blessing of baptism in the Holy Spirit and the charismatic gifts as described in the New Testament. This is a source of great joy for us and an important aspect of what God is doing in our world today,” says the People of Praise website.

For many non-believers, anyone who admits to a belief in speaking in tongues is immediately categorised as a Christian extremist. But that viewpoint is not necessarily one shared by Christians themselves – even those who do not personally believe in or practice speaking in tongues.

Furthermore, while speaking in tongues might be considered evidence of extremism by non-Christians, views within Christianity are more nuanced. While recent data is difficult to come by, a survey of Australian Christians in 1996 found that though Pentecostals were much more strongly approving of the practice of speaking in tongues than other denominations (over 90 per cent approval), Baptists and Churches of Christ also had considerably high levels of approval (37 per cent and 34 per cent), with Lutheran (17 per cent), Presbyterian (17 per cent) and Seventh-day Adventists (4 per cent) having the lowest.

“Overall, 14 per cent of attenders speak in tongues. Approximately 10 per cent of attenders in the Catholic, Anglican, Uniting and other larger non-Pentecostal denominations speak in tongues, revealing the broad impact of the charismatic movement. Half of all attenders have no opinion on speaking in tongues. Many attenders, particularly Catholics (62 per cent), are either neutral or do not know what they think,” a summary paper on the research said.

And, as the People of Praise’s website suggests, Pentecostals and Charismatics do make up a substantial percentage of the world’s Christians – about 27 per cent of all Christians and more than 8 per cent of the world’s total population, according to this Pew Forum Analysis.

Authority concerns expressed by former member of the People of Praise

One area of concern about the group that has been raised is its authority structures – particularly between men and women.

Adrian J. Reimers is an adjunct professor of philosophy at Notre Dame and was one of the founding members of the People of Praise. He says he was forced to leave the community after questioning the leaders’ authority over members’ lives and deviation from Catholic doctrine. In 1997, he published Not Reliable Guides, which criticised both the People of Praise and another similar community called Sword of the Spirit.

Reimer’s criticisms of the group include a culture of anti-intellectualism (despite individuals being encouraged to achieve high academic goals); a leadership philosophy that has the capacity to be used in manipulation; and a high emotional and intellectual cost for members who choose to leave the community.

“In short, to leave a covenant community is emotionally and intellectually far more difficult than to change colleges or careers or to break a wedding engagement. It is more akin to divorce. The departing member knows that he is leaving not just an organisation, but an entire way of life. Having invested himself totally in this life, he faces losing it all, and with it the most powerful experiences of religion he may ever have had,” wrote Reimer.

He also said “two features of the People of Praise pastoral system are particularly problematic: 1) lack of confidentiality, and 2) confusion of governance with spiritual care.” Reimers said this was owing to a structure where “one’s most intimate spiritual confidant is also the most immediate governmental authority,” explaining members must give at least 5 per cent of their income to the community.

“These two aspects of People of Praise headship are a matter of grave concern and must surely give us pause. Taken together they imply that the People of Praise member’s life is not his own, his or her self is not his or her own. As in Sword of the Spirit, the distinction between the secular and the religious is broken down, so that all one’s decisions and dealings become the concern of one’s head, and in turn potentially become known to the leadership.”

“We don’t try to control people.” – Craig S. Lent

In a New York Times article written in 2017 when Amy Coney Barratt was nominated to the judiciary, a current leader in the People of Praise answered these allegations. Craig S. Lent, who has almost 40 years of involvement in People of Praise, said that the group was not “nefarious or controversial”. Lent, who is also a Professor at Notre Dame, said the group was about building community and long-term friendships, and that members have a “wide spectrum” of political views.

“We don’t try to control people,” Lent told the New York Times. “And there’s never any guarantee that the leader is always right. You have to discern and act in the Lord … If and when members hold political offices, or judicial offices, or administrative offices, we would certainly not tell them how to discharge their responsibilities.”

He also spoke to the issue of relationships between men and women – another concern that is gaining widespread media coverage of late.

“Mr Lent said the group’s system of heads and handmaids promotes ‘brotherhood’, not male dominance, and that they recently dropped the term ‘handmaid’ in favour of ‘woman leader,'” the article said.

According to People of Praise’s website, “community life provides a natural support for marriages and families. This has led us to develop Marriage in Christ, a course for married couples. Marriage in Christ helps couples renew their love and affection for each other while building crucial habits of prayer, conversation and forgiveness. More than 1300 couples have completed the program.”

The People of Praise – contribution to their community

One final noteworthy characteristic of the People of Praise is that they have a strong sense of serving their community, especially those in need. As is the case in many Catholic communities, one way this is outworked is through education.

In 1981, “in response to a call from God”, the community established Trinity Schools – private Christian schools located in South Bend, Indiana, Falls Church, Virginia, and Eagan, Minnesota. According to their website, these middle/high schools have received a total of eight Blue Ribbon awards from the US Department of Education.

In 2002, some People of Praise members began moving into some of America’s poorest neighbourhoods in order to live closely with, and meet the needs of, these local communities. In those areas, they report having run camps for hundreds of children, repairing neighbourhood homes, hosting prayer meetings, growing healthy food on an urban farm. They say long-term local residents in some of America’s poorest neighbourhoods have credited them with not only being a positive, peaceful presence in local neighbourhoods, but also lowering the crime rates.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?