You’ll need to be cautious about singing when church returns. Here's why

Even more social distancing may be needed

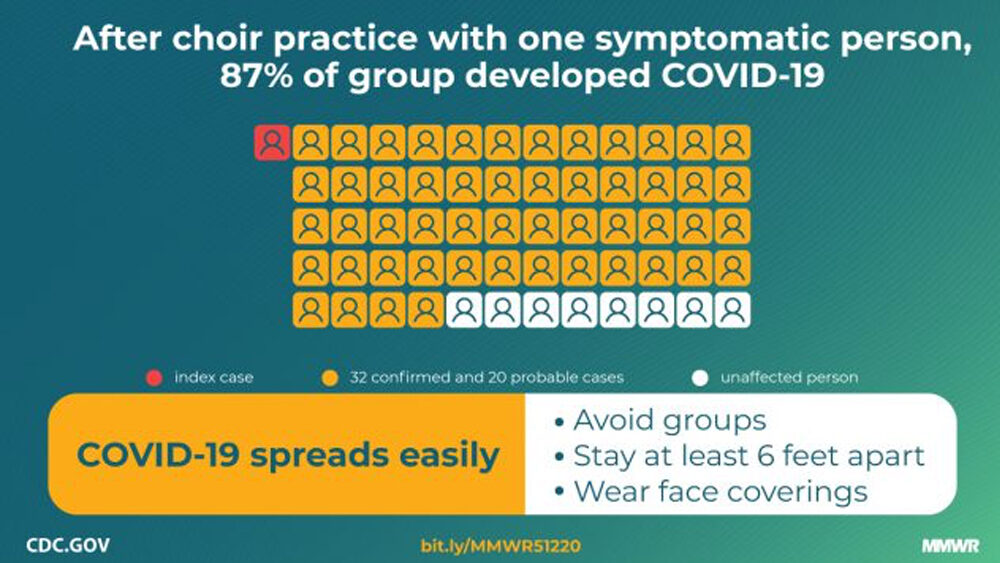

When the 61 members of Skagit Valley Chorale met for choir practice at the Mount Vernon Presbyterian Church between Seattle and Vancouver, back in March, they did not realise that 51 of them would become infected with COVID-19 as a result – and two would die.

The choir practice is now regarded as a “super spreader” event.

The act of singing, itself, might have contributed to transmission through emission of aerosols, which is affected by loudness of vocalisation.

A scientific paper published by the CDC, (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), explains why: “Following a 2.5-hour choir practice attended by 61 persons, including a symptomatic index patient, 32 confirmed and 20 probable secondary COVID-19 cases occurred (attack rate = 53.3% to 86.7%); three patients were hospitalised, and two died,” reads part of the CDC report summary.

“Transmission was likely facilitated by close proximity (within six feet) during practice and augmented by the act of singing.”

The place of singing and its possible contribution to the outbreak is described in the paper. “The 2.5-hour singing practice provided several opportunities for droplet and fomite transmission, including members sitting close to one another, sharing snacks, and stacking chairs at the end of the practice.”

“The act of singing, itself, might have contributed to transmission through emission of aerosols, which is affected by loudness of vocalisation. Certain persons, known as superemitters, who release more aerosol particles during speech than do their peers, might have contributed to this and previously reported COVID-19 superspreading events.

“These data demonstrate the high transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 and the possibility of superemitters contributing to broad transmission in certain unique activities and circumstances.”

The “loudness of vocalisation” is a risk factor – and this makes sense in that the exhalation of aerosol particles will travel further the more forcefully air is expelled from the lungs.

As churches around the world consider meeting again, they will need to work out how much notice to take of the Skagit story.

Singing, to a greater degree than talking, aerosolises respiratory droplets extraordinarily well.

The event was extraodinarily effective in transmitting the virus. The chances of those choir members who attended the March 10 practice becoming infected were 125.7 times greater than those who did not.

The presence of one asymptomatic member at that practice has been established by an investigation, the CDC reports.

There are other reports of similar cases at the Berlin cathedral, the Amsterdam Mixed choir and the Voices of Yorkshire choir.

Professor Erin Bromage, an Australian who is a Comparative Immunologist and Professor of Biology (specialising in Immunology) at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, discusses the dangers of singing, in a post about what risks to avoid during the pandemic. (Bromage’s blog has gone from 300 readers to three million in a few weeks, due to his coronavirus writing.)

“Even though people were aware of the virus and took steps to minimise transfer; e.g. they avoided the usual handshakes and hugs hello, people also brought their own music to avoid sharing, and socially distanced themselves during practice,” Bromage assesses about the Skagit Valley choir group.

“They even went to the lengths to tell choir members prior to practice that anyone experiencing symptoms should stay home.

“A single asymptomatic carrier infected most of the people in attendance. The choir sang for two and a half hours, inside an enclosed rehearsal hall which was roughly the size of a volleyball court.

“Singing, to a greater degree than talking, aerosolises respiratory droplets extraordinarily well. Deep-breathing while singing facilitated those respiratory droplets getting deep into the lungs. Two and half hours of exposure ensured that people were exposed to enough virus over a long enough period of time for infection to take place.”

So far this choir evidence is “anecdotal but compelling”, Professor Adam Finn of Bristol University told The Guardian.

Following social distancing practices will make a church service less risky than the Skagit Valley choir practice. But the tragic story of this choir, and others, will give churches – and possibly Bible studies, which often will be held in smaller rooms – reason to take care about singing.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?